france

new! Cathedrale Saint-Gatien at Tours

updated: Romanesque churches and cathedrals in south-west France updated: Romanesque churches and cathedrals in south-west France

the perpendicular or English style of cathedral

the fire at the cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris

cathedral giants - Amiens and Beauvais

Stone tracery in church and

cathedral construction

stone in church and cathedral construction stained glass and cathedrals in Normandy

fortified churches, mostly in Les Landes

cathedral labyrinths and mazes in France

using metal in gothic cathedral construction

Germans in France

cathedral destruction during the French revolution, subsidiary page to Germans in France

on first arriving in France - driving

France is not England

paying at the péage (toll station)

Transbordeur bridges in France and the world 2: focus on Portugalete, Chicago,

Rochefort-Martrou

Gustave Eiffel’s first work: the Eiffel passerelle, Bordeaux

a fifth bridge coming to Bordeaux: pont Chaban-Delmas, a new vertical lift bridge

France’s western isles: Ile de Ré

France’s western iles: Ile d’Oleron

Ile de France, Paris: in the context of Abelard and of French cathedrals

short biography of Pierre (Peter) Abelard

Marianne - a French national symbol, with French definitive stamps

la Belle Epoque

Grand Palais, Paris

Pic du Midi - observing stars clearly, A64

Carcassonne, A61: world heritage fortified city

Futuroscope

Vulcania

Space City, Toulouse

the French umbrella & Aurillac

50 years old:

Citroën DS

the Citroën 2CV:

a French motoring icon

the forest as seen by Francois Mauriac, and today

Les Landes, places and playtime

roundabout art of Les Landes

Hermès scarves

bastide towns

mardi gras! carnival in Basque country

country life in France: the poultry fair

what a hair cut! m & french pop/rock

Le Tour de France: cycling tactics

|

stained glass development

- Earliest from 10th century (900 - 999), but none has survived.

- 12th to 13th century (1100 -1299) - superimposed medallions

intense brilliant blues and red thick glass and leading smoothed down with a plane

Cistercians favoured grisaille windows

- 14th to 15th century (1300 - 1499) - the leading was

no longer handmade, the glass being thinner and so less heavy, thus

enabling larger windows to be made. Gothic canopies were put over human figures.

- 16th century (1500 - 1599) - delicately coloured pictures in thick lead frames, often copied from pictures, with

great attention to detail and perspective

- 17th,18th,19th century (1600 - 1899) - traditional

leaded stained glass often replaced by vitrified enamel or painted glass

- 20th century (1900 - 1999) - the necessity of restoring

or replacing very old stained glass led to both a return

to the original skills and styles, and to modern works,

generally done with greater imagination that the previous

three or four centuries.

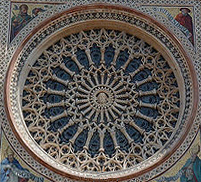

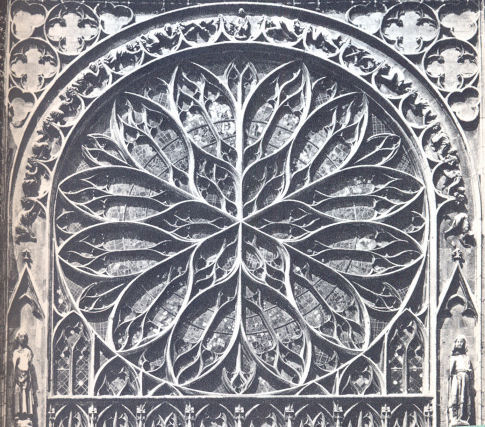

wheels

within wheels

West rose window

(exterior) at Orvieto cathedral,

mid-14th century [say 1350]

Circular windows have a tendency to rotate under the

slightest asymmetric pressure. The circle has to be maintained

with spokes of a wheel and arches. The outside of the

circle is, of course, one continuous arch. All these great

buildings, as they developed, were experimental. The centre

of the West Rose at Chartres is still, to this day, off-centre

by about a foot (30 cm), while the transept roses at Notre-Dame

de Paris had to be taken down and redesigned.

There is a war between making the window as solid as

possible and maximising the glass area, a war between

the simple shape and the complexity of the work of art.

Let us make circles within circles, as with the

Chartres glorious west rose. Or how about some squares, as

in the fine example of early plate tracery in Chartres’ north?

Elsewhere can be found triangles and pentagons [Laon

west rose], and perhaps hexagons would be used, or any other shape that

took their fancy - see the seven-pointed star at Rouen.

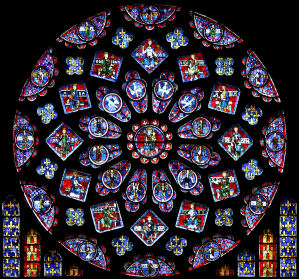

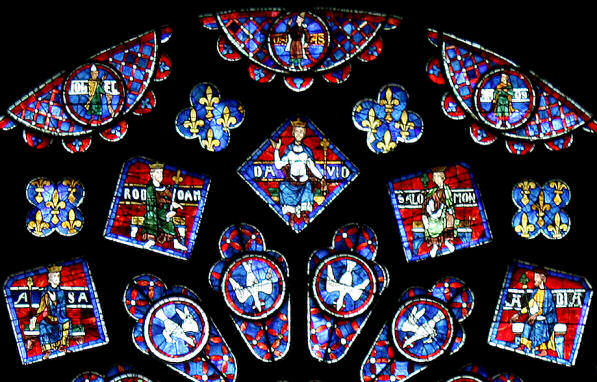

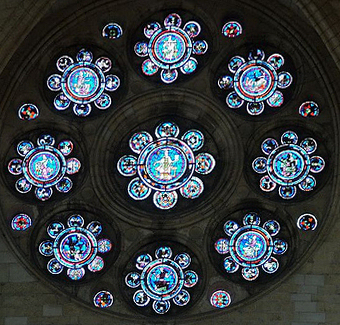

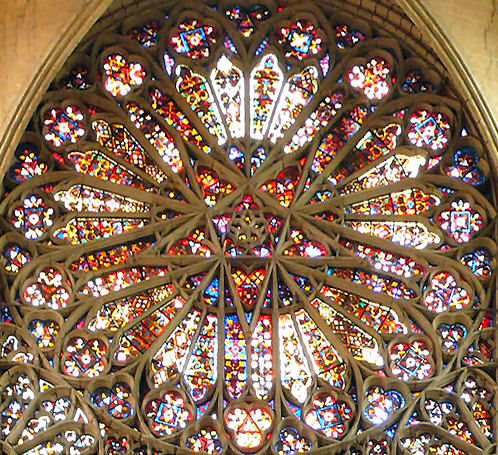

North rose at Chartres cathedral

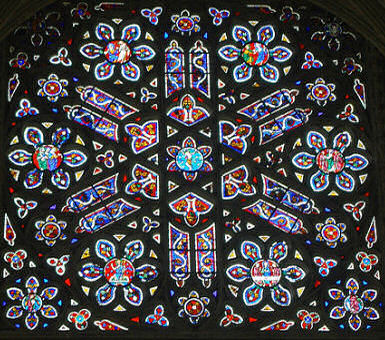

Detail of Chartres north rose, showing squares

with kings of Judea Asa, Rehoboam, David, Solomon, Abijah,

and medallions with prophets Joel, Hosea and Amos.

(For full lists, see box below.)

Chartres north rose

In the outmost ring of this rose, in medallions within a half-circle, are shown twelve prophets, each wearing a pileus or brimless, conical, felt hat. This was a symbol of freedom in ancient Greece and Rome, put on the newly shaven head of a freed slave (traditionally, slaves were required to be bare-headed). The pileus is closely related to the Phrygian cap, well-known as the cap of the french revolutionaries.

"The representations of this Phrygian, or Mysian, cap in sculptured marble show that it was made of a strong and stiff material and of a conical form, though bent forwards and downwards." {Quoted from penelope.uchicago.edu]

I wonder how the pileus became the dunce's hat?

the twelve prophets and the twelve kings of Judea

From 12 o'clock and going clockwise, the twelve prophets are Hosea, Amos, Jonah, Nahum, Zephaniah, Zacharias, Malachi,

Haggai, Habbakuk, Micah, Obadiah, Joel.

The ring of squares shows twelve kings of Judea. Starting from 12 o'clock and going clockwise, they are:

David, Solomon, Abijah,

Jehoshapha, Josiah, Ahaz, Manasseh,

,Hezekiah, Jotham, Jehoram, Asa, Rehoboam. |

Over the next century or two, as the experience of the

builders increased, the tracery became more decorative

and imaginative. The obvious wheels gave way to the more

seemingly organic lines of the flamboyant windows, such

as those at Amiens, Sens and Troyes.

|

|

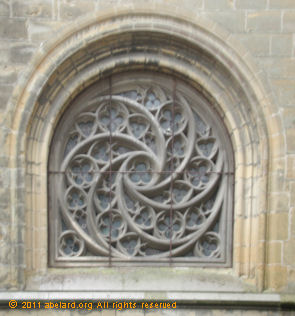

| A small spiral window at Bayonne cathedral |

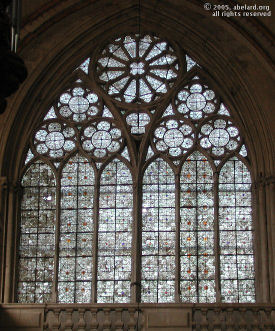

Lozenge, north rose window at Tours cathedral, made in c.1300

The heavy, central, vertical bar (mullion) for reinforcement was added in c. 1371,

as the builders were over-ambitious in their drive for ever more glass. |

These are windows with sweeping spirals and ‘paisley’

shapes. Tours has a lozenge rose; and then there is my very special snowflake window at Sees. Below the rose windows was usually a parade of

lancets, and often a new moon as a tiara filling the space

above.

By the mid-fourteenth

century [say 1350], the flamboyant style was fully developed.

The name flamboyant came from the fiery shapes

of the stone tracery, often also blazing with colour.

In such windows, all straight lines were eliminated, leaving

curving, curling flames. These roses were never to reach

the grand scale of the great gothic roses. The more intricate

stonework of flamboyant rose windows demanded only the

hardest, most consistent stone, which alone could manage

the stresses, even if achieving less ambitious sizes.

In the fifteenth to sixteenth centuries [1400 to 1599],

buildings that had been started centuries earlier were

completed with the latest style of stained glass window

- the flamboyant.

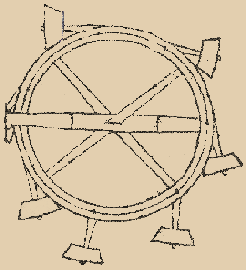

***section on stresses within wheels/spokes**** Tracery always in compression, spokes always in tension. (Note: the word spoke means a different thing in a bicycle wheel to a cartwheel.) Remember, a rose window does turn so the rose is in compression.

rose windows - cathedral window styles

In medieval christianism, paganism was still prevalent;

and there was also an excitement with a mysticism of numbers

that reached right back to Pythagoras. The construction

of the gothic cathedrals and their windows involved very

complex geometries, with on-going challenges to gain stable

structures within the circle.

|

|

Perpetual motion machine,

drawn

by Villard de Honnecourt, c.1225 - 1250 |

A cartwheel

Original image credit: LeoL30 |

Wheels were, of course, technology: wheels for carts

that worked, water wheels, mill wheels, wheels for raising

heavy loads, treadmills for providing power, the spread

of windmills. This was exciting, a new world was developing.

Little detail has come down to us, surviving the intervening

eight hundred years or so. One of the great treasures

that has survived is the design notebook of Villard de

Honnecourt. Who knows, perhaps we can even dream of a

perpetual motion machine powering this revolution? Or

the devil may be confused by a circular maze on the floor,

as can be seen just inside the entrance at Chartres cathedral.

Eight hundred years later, we must gain clues wherever

we may: an illuminated letter in a manuscript, a quick

builder’s sketch on the stones underneath the eaves,

and most of all from examining the buildings.

In a rough chronology:

- Simple oculus: a round hole in the wall

|

|

|

| View through

one open oculus to a glass-filled oculus on the other

side of the church belfry. |

Interior

view of same oculus to left, with grisaille glass. |

| Oculus on Romanesque church, with

Roman arches below. |

This what the lighting was like in the old Romanesque

churches. The pictorial assists for the clerics teaching

the illiterate peasants comprised murals of the moral

and uplifting stories.

The Romanesque walls were thick and load-bearing, windows

were weakened sections. Thus the buildings were dim,

illuminated by various forms of lamp. Glass was immensely

expensive, so even an oculus would let in the weather.

Buildings with thick walls do have the advantage of

insulating from the heat and cold.

Come the gothic building revolution and the fundamentals

changed. The realisation grew that between the pillars,

great walls of beautiful glass could turn these public

buildings into magical works of art.

You may read all manner of weighty tomes discussing

the minutiae of gothic architecture, but my impression

is that the walls of glass and uplifting beauty were

the prime drivers of the process. This can even be seen

in the amount of emphasis given by Abbé

Suger to his innovatory work at Saint-Denis in Paris,

and his much lower interest in the

mechanics of the building’s structure.

An example from Laon cathedral

Image

credit: Axe 02

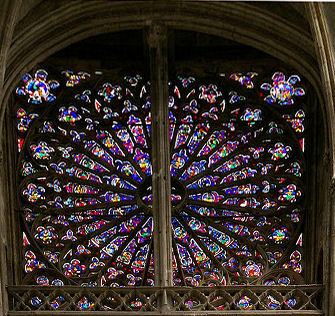

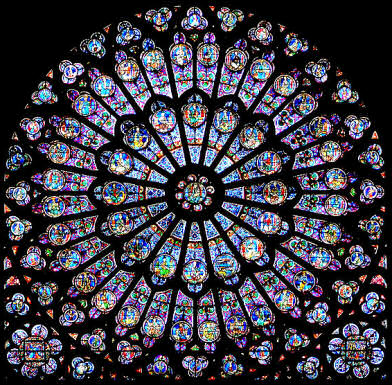

rayonnant rose window, south transept, Notre Dame de Paris

In this next general development, you see patterns mimicking lancet windows. Such windows can be seen in the south rose at Laon, the south rose at Rouen cathedral, (just below), and also the north rose of Ouen Abbey Church in Rouen.

Rouen south rose from the exterior, the glass being grisaille.

Note the highly unusual seven-pointed star at the centre.

Amiens north transept rose with pentagon and pentagram centre

The north rose at Amiens can be regarded as transitional in design, combining the lancets of the rayonnant and the stone tracery of the flamboyant style.

north rose, Sees cathedral

Central medallion: Jesus crucified.

Other medallions, from bottom left and going clockwise:

Jesus risen from the dead; holy women at the tomb; Jesus

appearing to Mary Magdalene; Jesus appearing to Thomas;

Jesus appearing to disciples of Emmaüs; Jesus recognised

by the apostles as he broke bread.

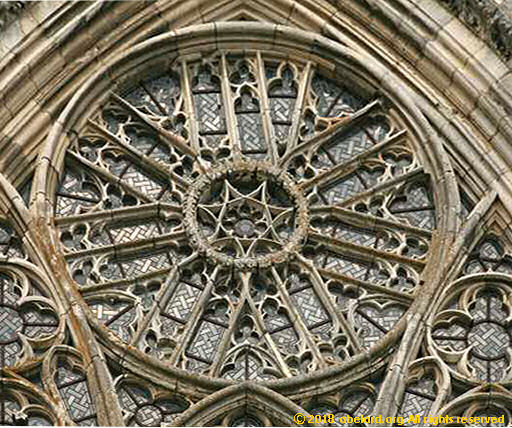

- Flamboyant (flames) - Amiens, Sens, Troyes, Auxerre, Sainte-Chapelle (Paris), Beauvais.

Notice that the tracery is moving steadily away from straight lines and plate tracery to ever more complex curves. The designs moved from rayonnant to flamboyant, that is from rays to flames. Such preferences are common fashions in art, as can be seen in modern times with Art Nouveau and Art Deco.

South rose at Amiens cathedral -

external view

As gothic architecture developed, there was less satisfaction

with the great gains in size of window alone. At Amiens, you can see the

much greater complexity of the Flamboyant window. You

can see that the tracery has become far more complex and

even extends outside the are of the rose. That tracery

is called blind tracery, whereas the tracery on the rose

itself is called open tracery. You will also see, around

the edge of the window, one of the best preserved ‘wheels

of fortune’.

![Wheel of fortune at St Etienne's, Beauvais [engraving] Wheel of fortune at St Etienne's, Beauvais [engraving]](/france/culture/rose/beauvais_stetienne_gravure.jpg)

Wheel of fortune at St Etienne's,

Beauvais [engraving]

As the mastery of gothic architecture proceeded, and

great areas opened up to the potential for being glazed,

shapes developed naturally to fill the appropriate spaces.

The circle fitted naturally into the leaping arches, as

did lancets into narrower, pointed openings.

These times were the true renaissance of Northern Europe,

with new techniques, burgeoning populations supported

by the development of deep ploughing on the rich soils

of the North, and growing knowledge.

classifying stained glass windows

Other ways of classifying stained glass windows:

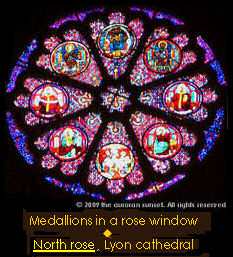

- Medallion windows

In stained glass, a medallion refers variously

to a circular, oval, square, diamond, and a variety of other shaped spaces,

generally one of many within the overall window

design, that contains a figure or figures.

Yoked medallions are two medallions partially joined

together.

- Figure windows like, for example, at Lyon cathedral.

- Story windows (often composed of medallions), such as the Thomas à Becket window at Chartres.

Also see the Saint Julian the Hospitallier window at Rouen cathedral.

- Rose windows - as well as on this page, see, for example, Lausanne rose window.

- Jesse windows (sometimes composed of medallions)

such as the Jesse window at Bourges cathedral.

- Grisaille windows

Grisaille is almost monochrome glass, each piece shaped as a

square or diamond and painted with black enamel

paint. From a distance, grisaille windows have an

overall greyish tint; hence the name grisaille,

meaning greyness in French.

Grisaille window, Poitiers cathedral

- Another way is by shape and tracery, say

- • lancet

pointed, as seen in the arches and windows with

a pointed head introduced in the Gothic period of

architecture. [From the point of a lance - a spear.]

• rose

Or the categories chosen could be - • glass colours and types.

so now for a bit on glass

glass making methods

- At first, in the earlier part twelfth century [1100-1199]

and before, glass was cast and the ingredients added

at significant instants during the melting process.

The result was called ‘pot-metal’.

- As the twelfth century progressed, glass was blown

so to give a much thinner product that was easier to

handle. This‘muff’ glass was blown into

a long cylinder shape. This was then cut open and flattened

into a sheet. Using a red-hot crozing-iron, the sheet

was cut up and the pieces of glass selected for their

position in the final composition.

glass ingredients

- Generally, to make the glass, two parts of beechwood

(or fern) ash were combined with one part of river sand,

the furnace heat fusing the mixture into a slightly

purple-coloured mass (the colour being due to manganese

impurities).

- Metallic compounds were added during fusion to give

the required colour:

- cobalt oxide (from Bohemia) made blue

- copper oxide made red

- silver chloride made yellow

- iron, often a natural contaminant of glass, can

produce yellow, brown or green.

This is why many bottles for beer etc are brown or

green - this is cheaper than purifying the glass.

technique - glass to window

- The design was drawn onto a whitewashed table.

- Pieces of glass were cut and selected so that internal

flaws were well exploited. The f1aws - such as bubbles,

grits of sand, streaks and variations in thickness -

all refract the light as it passes through the glass.

This causes the glass sparkle and sing.

- Some of the glass was shaped and immediately fitted

into the window.

- A much greater proportion received further treatment

with pigment made from a mix of iron filings and resin.

This brought out highlights, shadows, lines and other

details. The pigment was painted on to the glass to

create various details before being fired.

- A technique called flashing was used to make particular

colours and effects.

With flashing, a thin layer of one glass was pasted

onto another differently coloured piece, the ensemble

then being fired to fuse the glasses together.

The main glass receiving this technique was the dark,

ruby red glass. By building up as many as twenty or

thirty thin layers of red glass onto a clear base, fired

after layer added, a rich but not dark red colour was

achieved. This method allowed layers to be ground off

to give varying tones within the glass. Further colours

could be made by staining, rarely done in medieval times.

from

medieval glass to dalle de verre, or slab glass

In medieval times, the manufacture of stained glass

was an esoteric craft involving glass-blowing. The quality

of the glass varied greatly, in consistency, thickness

and so on. The surface varied, bubbles of air were trapped

in the glass, the colour varied, and since those days,

acids in the air and rain, and from pollution, pitted

the outside surfaces over the centuries. This can be

seen in the whitening of the surfaces.

You may think that all this variation is a problem,

but far from it. These variations are a good part of

what gives old windows such character, sparkle and glow.

In fact, restorations over the past century have often

done more harm then good, as some of the life has been

removed from the windows. However, as knowledge grows,

restorers are now often doing a better job.

Eventually, the old handcrafts involved in glass manufacture

were replaced by metal moulding and glass flotation.

The product became consistent, most of the bubbles were

removed, the surface became smooth and the colour evenly

distributed. This ended up in a product lifeless from

the point of view of the finished window. This product

became known, in a monumental misnomer, as ‘cathedral

glass’!

So the glass makers have had to learn all over again

how to produce a more appropriate material and result.

As modern science catches up with medieval craftsmen,

the palette of the stained glass artists is now becoming

good enough even to incite the envy of a 12th century

monk.

Added to the range of glass available, there is now

a great modern innovation dalle de verre, or

slab glass. This material has opened up the possibility

of embedding the inch-thick glass in concrete or resin.

As glass expands at approximately the same rate as the

concrete, these windows can be made to be structural,

as well as damned impressive.

To add still further to the lively colour and light

transmission qualities of this glass, the craftsman

deliberately chips the inside surface of the glass,

with a hammer, as can be seen in the photo just below.

great contemporary stained glass artists

For extended details, go to modern stained glass.

Unfortunately, great stained glass artists are few and

far between. The best I know is Gabriel Loire, who has

unfortunately died recently at a great age. The best example

of his work in England is at St Mary’s College Chapel,

Strawberry Hill, near Twickenham, using dalle de verre.

His son Jacques, and I believe his grandchildren, are

now involved in the business, which has a shop next door

to Chartres cathedral. However, his descendants are not

yet in the same class as Gabriel.

There is a prime example, in a single window, of Chagall’s

work at Chichester cathedral. He has also glazed a complete

church of 12 windows at Tudeley, Kent. But his definitive tour de force is at the 12 magnificent windows

at the chapel of the Hadassa Hospital, a little way out

of Jerusalem. There are also several windows in Metz cathedral,

but these I have not seen.

Matisse has created an impressive chapel at Vence in

Provence, designing practically everything within it,

including the stained glass windows. (Its visiting hours

are limited, so check carefully before visiting.)

See below for a very useful catalogue of stained glass in Britain.

recommended books

|

The rose window,

splendour and symbol by Painton Cowen

Thames and Hudson [UK], hbk, 2005

276 pages, 350 illustrations, 300 in colour

ISBN-10: 0500511748

ISBN-13: 978-0500511749

£29.99 [amazon.co.uk]

$63.75 [amazon.com]

Previously, Painton Cowen also wrote

Rose windows (Art & Imagination)

pbk, 1990

ISBN-10: 0500810214

ISBN-13: 978-0500810217

amazon.com / amazon.co.uk

Extremely well illustrated - the paperback version has

59 in colour and 82 black-and-white. Densely

packed with facts. An ideal primer to be carried around

with you on any visit. Like so many books, written by

informed hands, it is very badly organised and laid out.

My Thames and Hudson glued 1990 paper-cover version started

falling apart from early on, but always travels in its

own protective plastic cover to keep the pages in one

place. The newer 2005 hardback version has 300 colour and 50 b/w illustrations. It is a real doorstop of a coffee table book.

I can not resist giving these books five GoldenYaks,

if only because I know of nothing better. |

|

|

| Painton Cowen has also produced a very useful directory

of stained glass in Britain - |

|

A guide to stained glass in

Britain by Painton Cowen, # Michael Joseph

Ltd (June 10, 1985)

ISBN-10: 0718125673

ISBN-13: 978-0718125677

amazon.com / amazon.co.uk |

|

|

Experiments in gothic

structure by Robert Mark

MIT Press

pbk 0262630958

reprint: 1984 amazon.com / amazon.co.uk

If you want to understand the structure of the great

gothic cathedrals, this is the place to go. Some of it

gets a bit technical, Mark used polarised light, epoxy

plastic models and wind tunnels to work out the the loadings

and stresses in some of the great cathedrals. An absolutely

fascinating book to read, if you can stand the hard work

and the usual technical manual disorganisation.

As with Painton, I can not resist giving this book five

GoldenYaks, if only because I know of nothing better. |

end notes

- A good start on architecture can

be found in the introduction to the Michelin Green Guide

series.

- Naturally, the greater the magnification

of your binoculars, the greater the problem with handshake.

The greater the magnification, also the more bulk and

weight to carry around. Choosing a pair of binoculars

to suit you is, therefore, a compromise. The small cheap

ones can vary a great deal in quality - try them out

before buying.

- Halation

Light spilling from one section of glass to another.

However, these old craftsmen knew their trade, thus

thickening the leading where this is most likely

to occur. They even could take foreshortening into

account.

- Reims, like everything on the German

side of the World War One German front, lost a great

deal of its treasure, including glass, to German shelling.

The Germans used the cathedrals and churches in the

area for target practice. Hence, all the great stained-glass

treasures of France are to the west of that line.

The philistines of the French Revolution also did a

great deal of damage to French heritage (as mentioned

regarding Saint Denis above), as Cromwell did in England.

The third era of destruction across northern France

was occasioned in driving the National Socialists out

of France in 1944 in association with the D-Day landings.

- Being more precise, and

quoting from Mark [primarily form

p.115], “The Bourges sexpartite vault is estimated

to weigh 370,000 kg (820,000 lb), that is approximately

400 imperial tons. Whereas, Mark estimates that the

Cologne quadripartites to weigh 270,000 kg (600,000

lb), that is going on 300 imperial tons. [An imperial

ton is 2440 lb, while a short or American ton is 2000lb.]

The vaults also have rubble, or fill, to increase pressure

and to help stablise them. This included in the weights

quoted. Mark estimates that the horizontal outward thrust

on the main piers as 28,100 kg (62,000 lb) at Bourges,

and 31,300 kg (69,000 lb) at Cologne. The secondary,

lighter pier at Bourges, Mark estimates at 11,300 kg

(25,000 lb). This gives some comparison of the gains

attained by the Bourges sexpartite vault construction.

- St Etienne’s

is about 1.25 km south of Beauvais cathedral, if you’re

a crow. Unfortunately, this church is now in a very

sad state of repair. In Beauvais, most of the churches

are named for Saint Etienne!

|