To find a word, click on its first letter in the list below

A•B•C•D•E•F•G•H•I•J•K•L•M•N•O•P•Q•R•S•T•U•V•W•X•Y•Z•bibliography•end notes

- Labelled Illustrations:

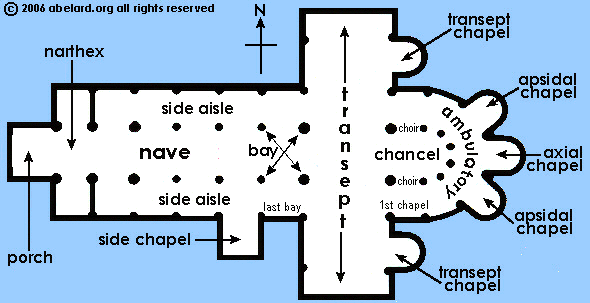

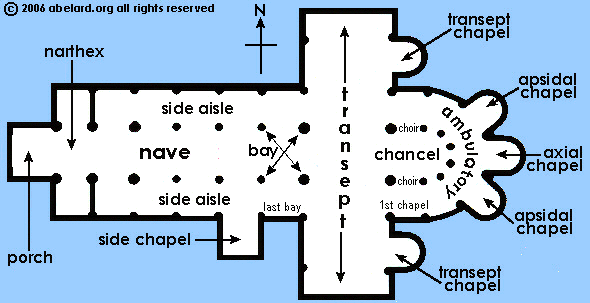

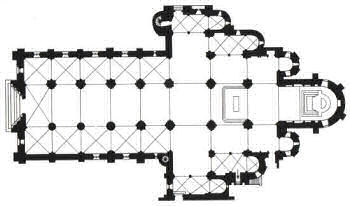

- Plan of a Gothic cathedral

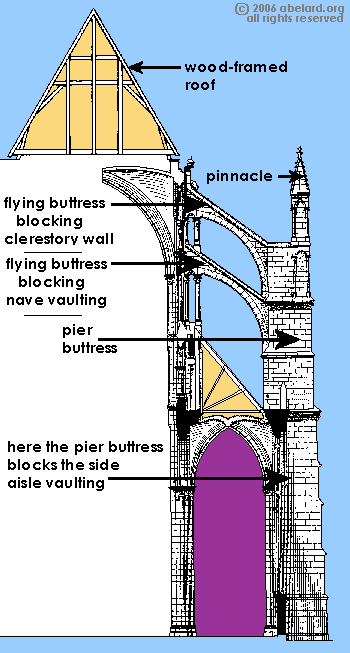

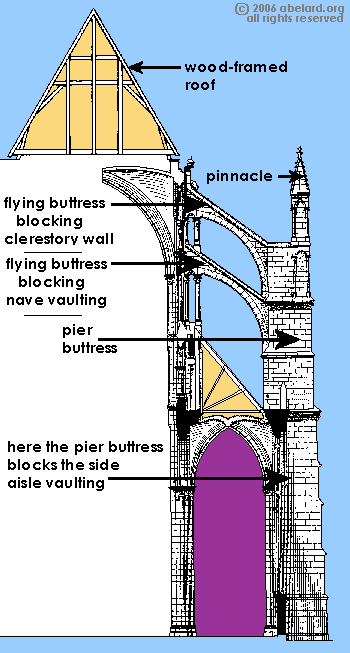

Buttressing

Half cross-section of Amiens cathedral to show buttressing and roof

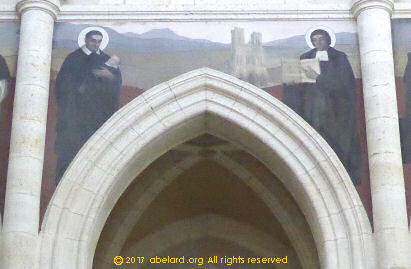

The various parts of cathedral arches and columns (at Notre-Dame de Saint-Denis)

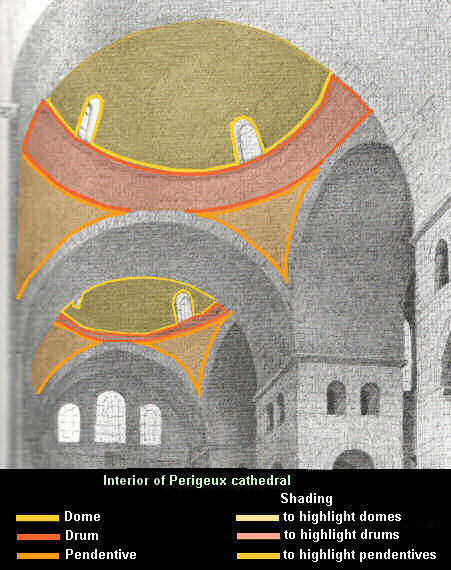

Pendentives, drums, domes

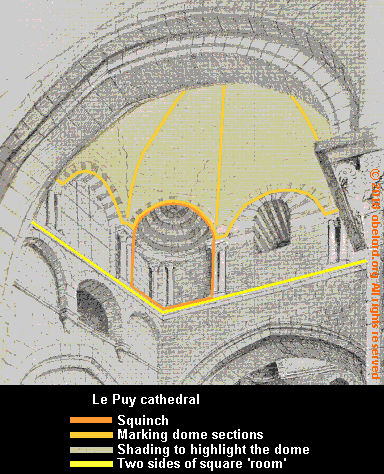

Squinches

Illustrating complex/composite columns at Amiens cathedral

Portal and porch (at Chartres cathedral)

- Abacus

- A flat slab forming the uppermost member or division of the capital of a column.

An abacus is sometimes called an impost or impost-block, but it is really an impost-block from which arches spring.

Another name for springer.

Ambulatory

- Walking area around the chancel.

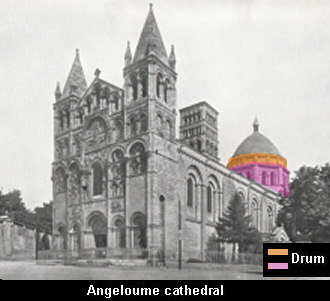

- Apse [Fr. abside]

- Semi-circular or polygonal ending to the chancel. The apse can be further extended by apsidal chapels.

plan of a Gothic cathedral - interior

plan of a Gothic cathedral - interior

Absidiole - French for a minor apse or 'apselet'. - The plan of Saint-Sever abbey church (below) has a central apse and six absidoles that form a complex, parallel and stepped system making up the chevet of Saint-Sever-sur-Adour Abbey church

- Arches and vaults [See also net; key stone]

pointed and Roman arches;

barrel and groin vaults; diaphragm, horseshoe and stilted arches

- An arch supports the stonework of a building above an opening such as a window or a door.

• Roman and Romanesque arches are rounded, formed in a continuous curve, usually a semicircle.

• Gothic arches are pointed, enabling them to support loads over varying spans.

|

france

new! Cathedrale Saint-Gatien at Tours

updated: Romanesque churches and cathedrals in south-west France updated: Romanesque churches and cathedrals in south-west France

the perpendicular or English style of cathedral

the fire at the cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris

cathedral giants - Amiens and Beauvais

Stone tracery in church and

cathedral construction

stone in church and cathedral construction stained glass and cathedrals in Normandy

fortified churches, mostly in Les Landes

cathedral labyrinths and mazes in France

using metal in gothic cathedral construction

Germans in France

cathedral destruction during the French revolution, subsidiary page to Germans in France

on first arriving in France - driving

France is not England

paying at the péage (toll station)

Transbordeur bridges in France and the world 2: focus on Portugalete, Chicago,

Rochefort-Martrou

Gustave Eiffel’s first work: the Eiffel passerelle, Bordeaux

a fifth bridge coming to Bordeaux: pont Chaban-Delmas, a new vertical lift bridge

France’s western isles: Ile de Ré

France’s western iles: Ile d’Oleron

Ile de France, Paris: in the context of Abelard and of French cathedrals

short biography of Pierre (Peter) Abelard

Marianne - a French national symbol, with French definitive stamps

la Belle Epoque

Grand Palais, Paris

Pic du Midi - observing stars clearly, A64

Carcassonne, A61: world heritage fortified city

Futuroscope

Vulcania

Space City, Toulouse

the French umbrella & Aurillac

50 years old:

Citroën DS

the Citroën 2CV:

a French motoring icon

the forest as seen by Francois Mauriac, and today

Les Landes, places and playtime

roundabout art of Les Landes

Hermès scarves

bastide towns

mardi gras! carnival in Basque country

country life in France: the poultry fair

what a hair cut! m & french pop/rock

Le Tour de France: cycling tactics

advertisement

advertisement

advertisement

|

Roman arches, église de Beylongue |

|

Gothic arch, Pontonx church |

|

While arches are essentially two-dimensional supports for the superstructures above them, a vault can be regarded as a three-dimensional expression of such support.

• A barrel vault is also known as a tunnel vault or a wagon vault.

• Fan vaulting is also known as a palm or conoidal vaulting.

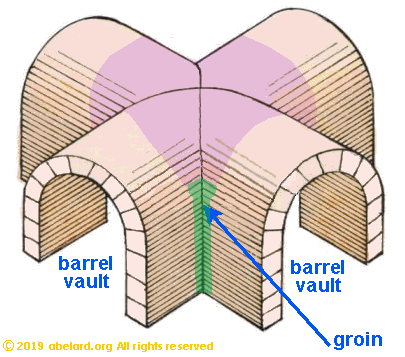

• A groin vault can be the intersection of two barrel vaults, see the pink areas in the diagrams below. This form naturally evolves into domes and pointed arches.

The word "groin" refers to the 'crease' between intersecting barrel vaults.

Roman architects determined that two barrel vaults intersecting at right angles formed a groin vault. However, the groin vault requires very precise shaping of the stone. This skill declined in the West as the Roman Empire ended.

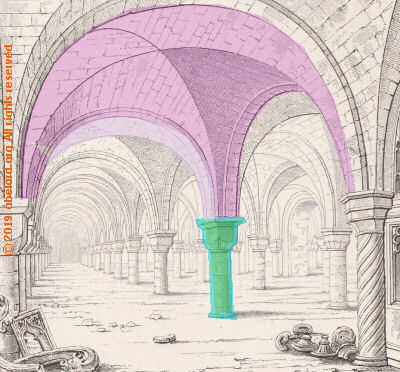

Groin vaults can also be found supported by four columns in extensive spaces such as crypts.

|

above: barrel vaults right: groin vaults (Canterbury cathedral crypt) |

|

|

In order to see how groin vaults relate to (probably earlier) barrel vaults, the illustrations just above have the same highlighting colours : pink for the vault (or its equivalent location) and green for one of the columns (or its equivalent location).

• A horseshoe arch is similar to the arch of a barrel vault, but having the two springer stones are placed slightly closer together than the widest part of the arch being supported.

Victorians, including church anoraks, loved to try and classify anything they could get their hands on. Here is an illustrated example of what they tried with arches.

• A stilted arch is one where the curve of the arch begins above the impost line, standing on the springer. The arch is on stone stilts!

When rounded Roman arches were used, they could well span different widths. However, being a semicircle, a wider Roman arch would be higher as well as wider. Thus stilts were used to maintain a uniform height, raising the smaller width and height arches to the same level as the larger ones.

Sometimes, barrel vaults and their associated groin vaults have been constructed in conjunction with pointed Roman arches.

• A particular arch is the diaphragm arch. Also known as flying screens, because the space between the arch and the surrounding walls and ceiling provide a solid screen with minimal support - it flies. The diaphragm arch has fire break properties, inhibiting

sparks and flames that rise with heat from flowing between different areas of the building.

(Note that in the image above, the areas beyond the diaphragm arch have been 'faded' to emphasise the diaphragm screen's separation from the apse beyond.)

Architrave

Another name for the lintel above a doorway. The architrave or lintel supports the tympanum.

[See porch.]

Archivault / archivolt

A decorative moulding around and under an arch, on its under surface, which follows the extrados of an

arch, forming an arch-like frame for an opening.

[See porch.]

Barn church

A common, approximate term for a cathedral or church where the aisles and the nave are of similar height; for example, see Poitiers Cathedral.

Barrel vault

See Arches and vaults

Base

This is the name given to the lower thickening of a column or a pillar that provides the column's foundation and support.

Note that an ancient Roman column had at its lower end a projection consisting of a a decorative, convex strip used for ornamentation or finishing and a scroll. With a few exceptions, mediæval columns have no lower projection or embellishment on its base.

Thus, with the scroll and other decorations removed, monumental stone cutters were spared considerable work. As a result, the 'cornice' could be part of the capital instead of being rebated into the column.

[Derived from Viollet Le-Duc.]

Belfry

Although the words ‘bell’ and ‘belfry’ seem related, the bel- portion of belfry

was not connected with bells until comparatively recently.

Etymology: The word ‘belfry’ goes back to a prehistoric Common Germanic compound.

The second part of the compound is the element *frij-, meaning “peace,

safety”; while the first element is either *bergan,

meaning “to protect”, giving a compound meaning of “a defensive place

of shelter”, or *berg-, meaning “a high place”,

and giving a compound meaning of “a high place of safety, a tower”.

The Old French word derived from the Common Germanic compound is berfrei.

First this meant “siege tower”, and later “watchtower”. Warning

bells were used in these towers, thus the word was also applied to bell towers.

In Old North French, berfrei mutated to belfroi. This, in turn,

caused English speakers to think of the native Old English word belle (Modern English, bell), and in Middle English became belfry meaning “bell tower”.

Bell wall / clocher-mur

A bell wall is an architectural element, a vertical, flat wall at the top or front of a building, usually churches, built to to accommodate bells. On a church, the bell wall is placed as the west facade.

[For more, see Fortified churches, mostly in Les Landes]

Bifurcating flying buttresses

Each of the sloping flyers splits in two (bifurcates), presenting a 'Y'-shape in a bird's-eye view.

[See Le Mans cathedral]

Boss

See Ribs and bosses

Bréteche

A bréteche is a small, rectangular, structure that juts out from the fortified building, overhanging an entrance way, so defenders can throw down, or let fall, projectiles onto approaching assailants.

[For more, including illustrations, see Fortified churches, mostly in Les Landes]

Butter Tower / Tour Beurre

Named because the tower’s construction

is said to have been paid for out of the dispensations granted to those who did not wish

to fast during Lent. As part of the dispensation, these people were

allowed to drink milk and eat butter.

Butter towers are part of Rouen and Bourges cathedrals.

Buttressing

Buttresses are stone

bracings that prevent cathedral walls collapsing from lateral and vertical pressures. As well as

the weight of the roofs and walls, pressure can come from winds pushing against these tall and

bulky structures. Buttresses are stone

bracings that prevent cathedral walls collapsing from lateral and vertical pressures. As well as

the weight of the roofs and walls, pressure can come from winds pushing against these tall and

bulky structures.

Flying buttresses are stone ‘bars’ that apply a horizontal force inwards towards the

cathedral wall. This force counter-acts the tendency of the walls

to bulge out from the lateral pressures.

The upper flying buttress redirects the

wind forces from the roof and the clerestory wall, guiding

them downwards into the pier buttress.

The lower flying buttress performs the same duty, but

for the outward lateral forces being exerted by the nave

vaulting.

The pier buttress blocks

the equivalent force from the vaulting of the side aisle.

The pier buttress also supports the flying buttresses,

bracing them so the cathedral wall does not move outwards.

The pier buttress also transforms the still sideways forces

into downward ones.

The pinnacle adds further weight to the pier buttress,

helping to anchor it against sideways pressure.

For much greater detail, see buttressing and chainage.

Cagot / cagotte (fem.)

Wretched and poor person belonging to a group banned for ill-defined reasons (originally, perhaps those affected by leprosy or other disease), once established in Pyrenean valleys of Béarn and in Gascony, as well as other parts of Western France and North Spain. The word was then applied derisively to bigots[(semantic evolution: leper > hypocrite > bigot].

Cagots were shunned, unable to mix socially or commercially, forced to form separate communities. They entered the church by a separate door, often deliberately made low so those entering had to bow as supposedly fit their lowly social station. Cagots were either banned from receiving communion or receiving it from the end of a long wooden spoon. Cagots were often only permitted to be a carpenter, butcher, or rope-maker.

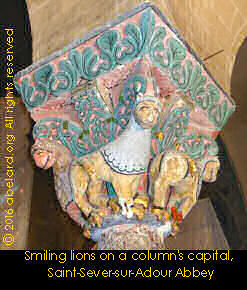

Capital

The top protruding stones of a column.

The capital at the head of a column spreads the load to the structures above, providing the transition from column to lintel or arch (see below left). For thousands of years, the capital has been an excuse for all manner of artistic decoration. Originating in ancient Greece, different styles are named after the period when they were prevalent.

The two main styles of Greek capital are:

Corinthian - With three superimposed rows of carved foliage (acanthus leaves) and small volutes (spiral scrolls) at the corners.

Ionic - a Greek style with the major decorations being large volutes on either side. These capitals are not common in Gothic buildings.

[A very comprehensive page of different capital types.]

By the 11th century A.D., historiated or figured capitals

appeared, decorated with humans, animals, birds and foliage.

Chancel

This is the part of the church to the east of the transept. The word choir (sometimes in English: quire) can be used

sloppily for this area, but more sensibly just applied to the area where the choir sings. The

chancel includes the high altar at its eastern end.

Chevet

A name used in France for the eastern end of the church in general, this we would call the apse. The chevet comprises an apse with radiating chapels beyond the aisle around the choir, the ambulatory. The resulting, more complicated structure became known as the chevet from the beginning of the 13th century.

Choir

area of a church designed to accommodate the liturgical singers, located in the chancel, between the nave and the altar. In some churches the choir is separated from the nave by an ornamental partition called a choir screen, or more frequently by a choir rail.

Claveau

Individual shaped stones in an arch, other than the keystone. Also known as a voissoir.

Clerestory

Also clerstory, clarestory, clerestorey, clarester, cleer story, clear

story, clearstory.

[Etymology: Commonly believed to be from the French, clere,

clear + story, stage of a

building or ‘floor’ of a house.]

Clere must here have meant ‘light, lighted,’ since

the sense ‘free, unobstructed’ did not yet

exist. This assumed derivation is strengthened by the

parallel blind-story, although

this may have been a later formulation in imitation

of clere-story. The great

difficulty is the non-appearance of story in the sense

required before c. 1600, and the absence of all trace of it in any sense in 14th,

15th, and chief part of 16th c. At the same time there is a solitary

instance of story in the

civic Rolls of Gloucester [R. Glouc.] (1724), which

may mean ‘elevated structure’ or ‘fortified

place’.

The noun estorie in Old French [OF]. had no such sense, but the past

participle estoré meant ‘built,

constructed, founded, established, instituted, fortified,

furnished, fitted out’, whence a noun with the

sense ‘erection, fortification’ might perhaps

arise.]

The upper part of the nave, choir, and transepts of

a cathedral or other large church, lying above the triforium (or,

if there is no triforium, immediately over the

arches of the nave, etc.), and containing a series of

windows, clear of the roofs of the aisles, admitting

light to the central parts of the building.

Clearstory is now more common

in the USA, whereas European usage prefers clerestory.

It is interesting to note that large numbers of the

more useful monographs on the architecture of medieval

France originate in the USA, while many of the more

philosophical studies originate in the United Kingdom. |

- Column

Left: a Sarrancolin marble column at the église of Rion-des-Landes

- A single, slim, vertical support with a cylindrical or a polygonal cross-section to its shaft (see on the right). A column always has a base and a capital.

Because columns are of relatively small diameter, they are only capable of supporting vertical down force and unable to support much oblique load,

like those generated by arches or vaulting.

[See buttressing.] [See pillar.]

Corbel- A projection jutting out to support a weight, such as a balcony, a corniche, or the first level of a roof. (There are also non-load-bearing versions.)

The carved version is called a modillon in French.

a row of modillons at Beylongue church, Les Landes

-

Below are corbels (marked with orange arrows) used to support the ribs of a sexpartite vault on a side aisle on the Collégiale Notre-Dame d'Uzeste, Gironde.

The springers supporting a vaulting arch from a pillar are marked with blue arrows.

The arches shared between the main aisle (to the right) and the side aisle (to the left) are indicated with purple arrows.-

Corbels supporting sextite vaulting ribs, Collégiale Notre-Dame d'Uzeste

[Etymology: The word corbel devised from the Latin word, corbellus - diminutive of corvus, a raven; or from corbeau - a crow, with a corbelet being a small corbeau.]

Cornice

- On a vertical surface such as a wall, the highest horizontal area that juts or sticks out, such as mouldings along the top of a wall or just below a roof line.

[Etymological origin : ledge]

- Crenellations

- Walls with lower and higher parts that provide cover for defenders protecting a building. The cut-out, lower parts are called crenels. Found on fortified churches such as that at Beaumont-du-Périgord.

- Crypt

- A subterranean room or vault, especially one beneath the main floor of a church, used as a burial place or for, frequently secret, meetings.

[Etymology: From Greek kryptḗ (n., f.) - a hidden place, kryptós - hidden (adj.),krýptein - to hide (vb.) 1375-1425 for sense "grotto"; 1555-65 for current senses. Thus related to cryptology or code-making. ]

- Dado

- [Public architecture] The lower part of a wall; or

the part of a pedestal between the base and the cornice.

[Domestic architecture] The wall below the dado rail and above the skirting board.

- Delit

- This word was originally written as de lit, but the two words have elided over time, acquiring an acute accent. De lit means 'out of bed', in this context not lying parallel to how the sedimentary strata were laid. In architecture, this term refers to the cutting and placing of a stone for construction. Délit contrasts with au lit, 'in the bed'. Traditionally, the stone is cut and laid down in accord with the geological strata of the quarry bed of which the rock is constituted, which strata are substantially horizontal. Laid this way, the stone resists the pressure of the loads that are exerted on it.

In contrast, la pose en délit (posing or placing against the grain) consists in placing the stone so the strata (bed) are vertical. Placing en délit causes a risk of vertical cracking or disintegration. This is why it is prohibited (in France) when using "laminated" materials such as certain limestones and shales; vertical placing/en délit being more suitable for homogeneous materials. However, construction en délit was much used by the Romans, and later by the builders of the flamboyant Gothic cathedrals - for aesthetic reasons (the visual smoothness of the stone, achieving great heights without joints) and, in fact, as demonstrations of technical virtuosity.

Although stone cut en délit is prone to shattering under compression, by cutting en délit, much longer pillars, tracery and other slender structures may be achieved. Compressive shattering can be mostly avoided by ensuring that the stone concerned is not significantly load-bearing.

The architectural use of the word délit is pretty obscure. Nowadays, the word délit in France is much more commonly encountered as meaning a minor crime. The three levels of crime are contravention, délit and crime. A contravention is the least serious offence: irregular parking or light violence, for example. Next is a délit: theft, abuse of public property, discrimination, moral harassment, sexual touching, manslaughter ... Crime is the most serious offence: murder, rape ...

These two usages of délit are not etymologically related in any way. Délit, a minor crime, comes from the same root as delinquent and delinquency.

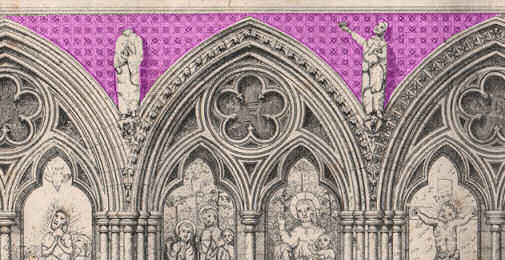

- Diaper

- Pattern created by repeating small, often geometrical, designs. Used to decorate walls, and as backgrounds in illuminated documents, such as books.

[See spandrel.]

-

- Diaphragm arch

- See Arches and vaults

- Dome

- Hemispherical covering or roof over a large space, in cathedrals and churches. Thus, a dome may be placed at the crossing of the nave and transepts. A dome is an architectural structure, as the circular base of the dome rests usually on four pillars having a square footprint.

The form of a dome is an arch, a hemispherical vector or line, rotated 180 degrees, thus making a 360° half sphere or hemi-sphere.

See Pedentives, squinches, drums, domes and lanterns for illustration and further discussion.

- Donjon

- Great tower or innermost keep (bailey) of a castle. Originally the word dungeon was used in this sense (see, for instance, Chaucer).

Later, the word was changed from the sense of great tower to the modern usage of dungeon, while donjon is now used for the original sense.

- Dosseret

- Supplementary cubical block or super-abacus, [super, Latin for over], which is often taller than the capital itself, placed over an abacus of Earl

Christian, Byzantine, and Romanesque capitals.

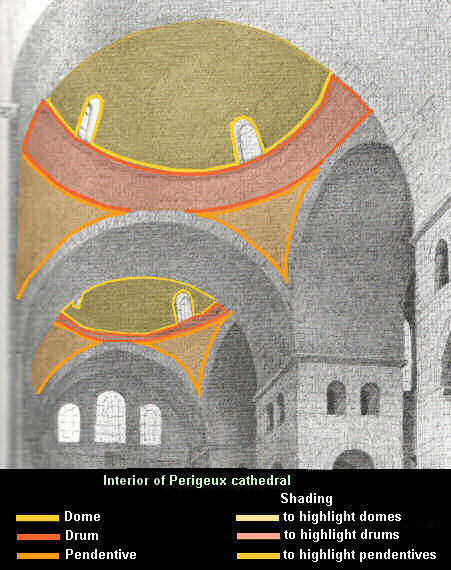

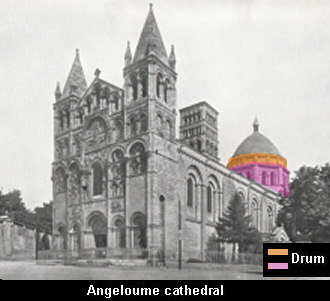

- Drum

- Where the nave and transepts of a cathedral cross, that crossing can be surmounted by a structure that straddles the four corner pillars of the crossing. A drum, an empty cylinder, is one such structure. A drum can be of short stature, or can have its height extended to become a lantern or a tower. Lanterns are pierced by windows that enable light to enter the cathedral from the exterior.

See Pedentives, squinches, drums, domes and lanterns for illustration and further discussion.

-

- Embrasure

- An opening for a portal or window built into a thick wall. An embrasure often has angled sides, so that the opening is larger on the inside than the outside. These were used to allow archer or gunnery fire. This type of opening was flared inwards, thus the embrasure was very narrow on the outer side but broad inside, so that the archers had freedom of movement and sighting, and of their assailants, who had the greatest difficulty in seeing the defenders.

[Etymology: Old French: embraser - to cut at a slant.]

[See meurtiere.]

advertisement

Engaged column- A curved shaft built directly into a wall. It is like any other column, but it is physically connected to the wall, being a part of it. An engaged column is load-bearing, helping to hold the ceiling as well as providing support buttressing to its surrounding wall.

- Extrados

- Exterior or upper curve of an arch

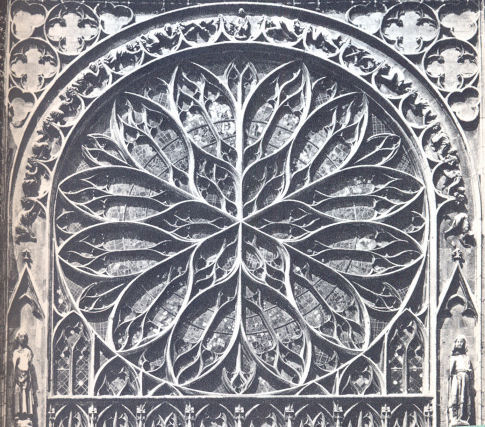

- Flamboyant

- Literally, flaming. This refers to the way flamboyant shapes in church and cathedral windows often are reminiscent of flames.

As gothic architecture developed, there was less satisfaction

with the great gains in size of window alone. The result was the development of the Flamboyant window and its greater complexity, as can be seen in the south rose window at Amiens.

South rose at Amiens cathedral - external view

South rose at Amiens cathedral - external view

- Forest

- Until very recently, the roofs of the great cathedrals

were framed in massive and complex

structures of wood, often known as ‘the forest’.

Due to its vulnerability to fire, the ‘forest’

has been a great bane for gothic cathedrals from the

earliest times. This regularly caused much damage to

the cathedral at large, by damaging the stone work,

as well as setting

fire to the cathedral structure and furnishings.

See the fire at the cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris.

Now, restoration is turning to reinforced concrete

for roof framing as, for instance, at Noyon. Iron and steel has also been used on occasion in the past (see Chartres - roof space: le charpente de fer).

- Fortified church

- A church built with sufficient reinforcement and size that it can provide shelter to the town or bastide’s population in times of trouble. See also Beaumont-du-Périgord.

[For comprehensive, illustrated essay, see Fortified churches, mostly in Les Landes.]

- Gallery

- Another name for a tribune.

- Gargoyle

- A purposeful decoration of a rainwater sprout projecting from a gutter take the water away

from the building, usually in the form of a fantastic or grotesque figure. In the Middle Ages,

gargoyles were utilitarian.

In the 19th century, the French architect

who restored (some may say over-restored) many public buildings in France, Eugene Viollet Le-Duc added the ‘gargoyles’ to Notre Dame de Paris in a fanciful, romantic notion, more

akin to Disneyland than reality.

“These gargoyles ... were not mere avatars of the Middle Ages, but rather fresh

creations—symbolizing an imagined past—whose modernity lay precisely in their

nostalgia.”

[Quoted from The Gargoyles of Notre-Dame]

This a gargoyle:

And this is what a gargoyle looks like from above. Note that the rain runs into the beastie’s head to spurt from its mouth, so projecting the water away from the building.

-

The following photo shows grotesques, not gargoyles. They are not conduits for rainwater.

These were put up high on Notre Dame de Paris by the ubiquitous Viollet Le-Duc in the nineteenth century, long, long after this cathedral was built.

Etymology: The word ‘gargoyle’ comes from Old French gargurl or gargolle,

meaning ‘throat’, or ‘gullet’, or even ‘gutter’.

‘Gargle’ has a similar etymological origin - the root gar-, ‘to

swallow’.

-

- Gisant

- A funerary sculpture of Christian art depicting a recumbent person (as opposed to a praying or supplicant position) generally on the back, alive or dead with a blissful or smiling appearance (as opposed to being 'chilled to the bone'). The image is usually placed on top of a cenotaph or, more rarely, a sarcophagus. When it exists, the gisant is the main element of decoration for a tomb or funerary niche. By extension, a carved or engraved gisant in bas- or half-relief on a tombstone can also represent the effigy of a great personage or noble.

Tombs of Richard I [Richard the Lionheart] and Isabella, wife of John Lackland [Richard's younger brother]

Royal Abbey of Our Lady of Fontevraud (or Fontevrault)

Tombs of Richard I [Richard the Lionheart] and Isabella, wife of John Lackland [Richard's younger brother]

Royal Abbey of Our Lady of Fontevraud (or Fontevrault)

Etymology: Gisant is the present participle of the verb gésir [Fr.] : lying down, lying (usually sick or dead). The same verb is used in the phrase "ci-gît" ("here lies"). Gésir is a defective verb that is only used in the present, the imperfect, and the present participle.

- Grisaille

- Almost monochrome glass, each piece shaped as

a square or diamond and painted with black enamel

paint. From a distance, grisaille windows have an

overall greyish tint; hence the name grisaille,

meaning greyness in French.

- Grotesque

- A grotesque is a fanciful statue, created in the 19th century or later, placed high on an cathedral or church. Unlike a gargoyle, a grotesque does not direct rainwater away from the building, it is merely decorative.

- Groins and groin vaults

- See Arches and vaults

- Halation

- Light spilling from one section of glass to another.

However, these old craftsmen knew their trade, thus

thickening the leading where this is most likely

to occur. They even could take foreshortening into

account, as you stare up at human figures placed on high.

- Horseshoe arch

- See Arches and vaults

- Impost / imposte (Fr.)

- Slab, or row of stones, above a column capital at the point of the spring of an arch. The arch rests on the impost.

Another name for springer.

- Intrados

- Inner curve of an arch.

advertisement

- Jesse tree

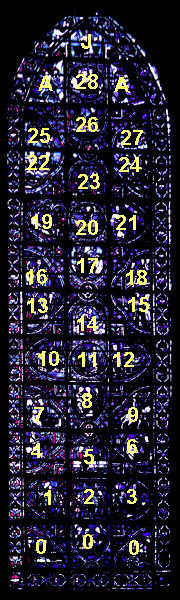

- A tree of Jesse is a tradition in stained glass windows, giving a

visual representation of the genealogy of Jesus. The name ‘Jesse Tree’

comes from the Book of Isaiah 11:1, where Jesus is

described as a shoot coming up from the ‘loins’ of Jesse,

the father of David. As with most story windows, a Jesse window is read from base to top.

In stained glass depictions, the tree comes from the

side, or the navel, of Jesse lying on a bed. The lineage

shown includes the following list, but may be longer,

including other ancestors such as Solomon.

The characters in the list below of a typical Jesse

tree are accompanied by symbols, which may decorate

the Jesse tree. Bible sources are also included.

Adam and Eve, symbol : apple

(Genesis 2:4-3:24)

Noah : ark or rainbow (Genesis

6:11-22, 7:17-8:12, 20-9:17)

Abraham : knife (Genesis

12:1-7, 15:1-6)

Isaac : ram (Genesis 22:1-19)

Jacob : ladder (Genesis

27:41-28:22)

Joseph : colorful coat (Genesis

37, 39:1-50:21)

Moses : tablets of the law

(Exodus 2:1-4:20)

David : harp (1 Samuel 16:17-23)

Isaiah : lion and lamb (Isaiah

1:10-20, 6:1-13, 8:11-9:7)

Mary : lily (Luke 1:26-38)

Elizabeth : small home (Luke

1:39-55)

Joseph : hammer or saw (Matthew

1:18-25)

The lineage shown at Le Mans comprises only five characters of a much greater possible list:

|

a

|

- Key stone, keystone

- The top, central stone of an arch is called the keystone. It is the last stone put in place, locking the other stones in position.

See also voussoir.

According to Viollet Le-Duc, clef (in English, key) when applied to masonry, means the central arch stone that closes an arch, positioned on the vertical line from the top centre of this arch.

For rounded [Roman] arches, there is a single, central keystone.

The Roman/rounded arch also has other arch stones, and at its base on each side there is a springer, (E on the labelled photo above).

Roman arch, église de Taller

For pointed [Gothic] arches,

the arch's apex meets at a joint between the two highest stones. In these cases, in fact, the keystone is two half keystones, which can also be regarded as arch stones, one each side of the joint at the arch's apex. A pointed/Gothic arch is shaped from two part circles, and is composed only of springers and arch stones. It is probable that if a Gothic arch keystone is made of only one stone, it would probably shatter from the pressures involved.

[See also the two Ks to the right in the labelled photo further above.]

|

|

Gothic arch, Pontonx church

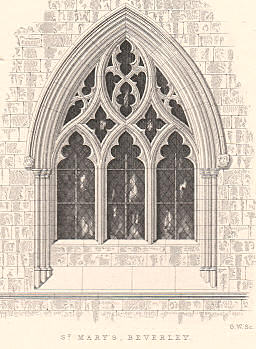

Left : Gothic window, Beverley Church, England, drawing from

Decorated Windows, E. Sharp M.A, publisher: J van Voorst,

1841 [plate 43, vol. 2 of 2 vol.s] |

And here is a composite illustration, with the keystones marked in orange, from Viollet Le-Duc

Labyrinth / maze- "What is the difference, it may be asked, between a

maze and a labyrinth? The answer is, little or none. Some

writers seem to prefer to apply the word "maze" to

hedge-mazes only, using the word "labyrinth" to denote

the structures described by the writers of antiquity, or as

a general term for any confusing arrangement of paths.

Others, again, show a tendency to restrict the application

of the term "maze" to cases in which the idea of a puzzle

is involved.

It would certainly seem somewhat inappropriate to

talk of "the Cretan Maze" or "the Hampton Court

Labyrinth," but, generally speaking, we may use the

words interchangeably, regarding "maze" as merely the

northern equivalent of the classic "labyrinth." Both

words have come to signify a complex path of some kind,

but when we press for a closer definition we encounter

difficulties."

[From Introduction, Mazes and Labyrinths by

W. H. Matthews, 1922]

-

- A 'simply connected' maze has just one path that leads from its entrance at the exterior, that winds its way to eventually reach the centre, as can be seen at Amiens, Reims. A simply connected maze may include dead ends, though this is not so at Amiens or Reims. A maze or labyrinth with dead ends can be solved - finding one's way to the centre or out again - by keeping a hand touching one wall while going along the paths. Eventually, the goal will be reached. The labyrinth at Knossos in Crete was said to be of this type.

A 'multiply connected' maze has walls which are detached one from another, making separate closed circuits. The hedge maze at Hampton Court in England is a well-known example. Such a maze requires a more complex set of rules to reach the centre, or exit. These were determined by Pierre Charles Trémaux [active in the late 1800s].

-

- Mark on the right continuously

any path you take. At a junction, continue to mark,

taking any path you wish.

- If you encounter a previously marked (old) path or a dead end, turn around and

continue marking back the way you came.

- If when walking on an old path (marked on the left), you arrive at a previously marked juncture, take and mark any new path if available, if not take an old path.

- Never take a path marked on both sides.

Note that Trémaux only proposes making a mark at the start or end of a path, but making a continuous line could be more obvious and reliable.

- related document:

- cathedral labyrinths and mazes in France

- Lancet

- Pointed, as seen in the arches and windows with

a pointed head introduced in the Gothic period of

architecture. [Etymology: From the point of a lance - a spear.] Also see Ogive.

- Lantern

- Where the nave and transepts cross, that crossing can be surmounted by a dome or a tower, straddling the four corner pillars of the crossing.

If the tower has glassed openings that let in light down to the floor of the crossing, it is called a lantern or lantern tower.

Lantern tower forms include

• in stone - as at Coutances, Normandy in France,

• in wood - as at Eely in Eastern England, and

• domed lantern, also called a cupola - as at Burgos in Spain.

[See Pedentives, squinches, drums, domes and lanterns for illustration and further discussion.]

related document:

lantern towers of Normandy and elsewhere

- Light

- A smaller section of a stained glass wiindow, examples marked in pink in the accompanying illustration.

- Lintel

- Horizontal stone bar supporting a tympanum.

Also the structural support above a door or a window.

[See Porch.]

advertisement

- Machicolations

- Openings in floors that project beyond the castle wall. Missiles can be dropped on unwanted visitors below.

Boiling oil was not used - oil was an expensive product, and heating it would use wood in short supply in a siege situation.

Machicolations are found on fortified churches such as that at Beaumont-du-Périgord.

- Medallion

- In stained glass, a medallion refers variously

to a circular; oval, square or diamond shaped space, a section in a window,

generally one of many within the overall window

design, that contains a figure or figures.

Yoked medallions are two medallions partially joined

together.

- Meurtrière

- A meurtrière is the generic name for arrow-slit or loophole. They can be further divided into archières, cannonières and archière-cannonière.

[For more, see Fortified churches, mostly in Les Landes.]

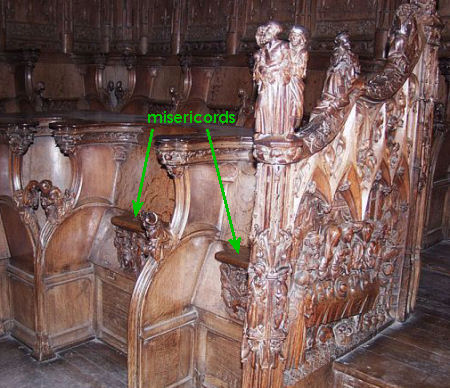

- Misercord

- A little ledge on which priests and monks could rest their bottom while

appearing to be standing, they not being allowed to sit in “the presence

of the Lord” and ceremonies could continue for

hours on end. These ledges are called misericords (also spelt misericorde, misercord = mercy, Fr.), and were justified by being the location

for fancy carving on religious topics or stories from

the bible.

The choir stalls at Amiens are considered to be among

the best anywhere. They certainly are splendid, but I

prefer the

choir stalls at Auch. They are an extraordinary treasure

hidden at the heart of that cathedral, with primitive

naive energy, both in the subjects and in their implementation.

Two choir stalls at Amiens cathedral with their misericords marked.

Two choir stalls at Amiens cathedral with their misericords marked.

- Modillion

- One of a line of ornamental stone brackets projecting beneath a cornice. The French spelling is modillon.

cat modillions, Saint-Pierre, Pathenay-le-Vieux

cat modillions, Saint-Pierre, Pathenay-le-Vieux

- Motte

- In the long past, many village churches in Les Landes were built on higher points, including the artificial heights of a major heaping of mud, rocks, and stones called a motte.

[For more, see Fortified churches, mostly in Les Landes]

- Muldenfaltenstil

- Sharp, hairpin-like folds in clothes, seen in stained glass windows and statues.

|

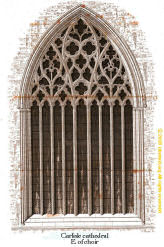

- Mullion

- The vertical stone bars that divide the lights (sections) in larger windows.

[Left: window with nine lights and eight mullions, Carlisle cathedral.]

Left: window with eight mullions

- Narthex

- A vestibule, found in some earlier churches. This is usually archaic now.

In the early church, there was a split between the Catechumens, that is the unbaptised faithful, and the Initiates. Thus, baptisms were held in the narthex, before entry into the church proper to be with the baptised faithful. On occasion, the narthex would be a colonnaded porch in front of the main church. Sometimes, this was called a 'galilee'. In England, such entry porches can still be seen at Durham, Ely, and Lincoln cathedrals.

Thus, the Catechumen would attend the first part of the service and then leave. After prayer and sermons would come the communion and the creed for the Initiates. The Church was almost in two parts, some even call it two Churches. As the Church grew in size, it gradually merged and became the enormous cathedrals and churches coping with the increasing populations.

However, the choir and the nave remained as a distinction

between priests and people. This was adjusted quite recently, as Vatican II changed services to the vernacular

and turned the altar so the priest faced the people.

Another purpose of the narthex, remembering that British cathedrals were mostly monastic foundations, was where the monks could meet with local dignitaries ('civilians') or females.

- Nave

- Main body of a church or cathedral. From the french word for a ship, the nave looking

similar to frame of an upturned ship.

- [Etymology: Nef is the French word for ship or vessel]

- Net

- The spaces enclosed by the framework of ribs supporting vaulted ceilings.

- The net is the web of stone between the arches of the vaults.

These continuously curved shapes, like a spider’s web or an eggshell, have both redundancy and

surprising strength. (If a spider’s web or an eggshell is broken, the main structure remains

functional.) I am told that the web at Notre Dame de Paris is only about 6 inches thick, yet it has

held up for 800 years. In the photograph below, you can see the web at Reims cathedral pierced by a German shell in 1915.

See also Spoila.

For much more technical detail, see Sexpartite vaulting.

-

Oculus- a round hole in the wall. [Illustrations]

- Ogive, ogee, ogyve, augee

- This term is used widely and confusedly in several areas of language, including in statistics, as well as in architecture. 'Ogive' is used to label/describe a slope that changes direction, as in the letter S, or in a hyperbola. Thus, in architecture, 'ogive' is sometimes used of ribbed vaults or the cross-section of re-entrant (s-shaped) mouldings.

Etymology: Said to have been used by Villard de Honnicourt, 13th century; probably from auge, French for trough, possibly coming from Latin alveus.

- Orientation of a cathedral

- It is conventional to refer to the apse end of cathedrals as the east, and the

other three points as west, south and north. It is also common to refer the the ‘east’ end of the

cathedral as being oriented towards Jerusalem.

In fact, many of the cathedrals were built on sites which had long been the place of previous cathedrals.

These had often been burnt or otherwise damaged, or overtaken by changing fashions and growing

congregations. And going beyond that into the past, they were sites of Roman and pagan temples.

The demands of site and geography could also be a consideration. Thus, if you check, you will often find

that cathedrals are not reliably oriented east-west, but their orientation is quite variable. The magnetic compass was

only being introduced in Europe in the late 12th century, by which time the sites of most cathedrals

were well established. So maybe the cathedral builders had used the North Star.

However, the convention remains. The main altar/apse is at the ‘eastern’ end, the prime public entrance

is at the ‘west’, with side entrances at ‘north’ and ‘south’.

advertisement

- Parvis

- The area in front of a cathedral. [See Cathedral of Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges - the cathedral of the Pyrenees]

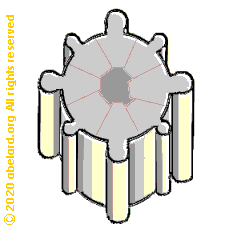

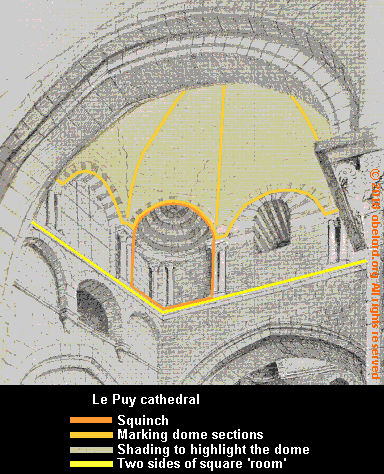

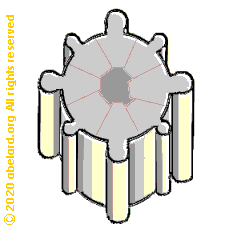

- Pendentif : pendentives, squinches, drums, domes and lanterns

Bridging the difference

Cathedrals are built as a series of square 'rooms' without internal walls and with columns at the corners of each 'room'.

The nave-transept crossing is essentially a large, wall-less, square room. Adding an circular or octagonal drum or lantern, or a hemispherical dome, above it, requires a three-dimensional solution to join the two parts together and provide adequate support for the superstructure.

Pendentives are one such solution, squinches are another. Pendentives are simpler in appearance, but more complex in their geometry.

Pendentives are one such solution, squinches are another. Pendentives are simpler in appearance, but more complex in their geometry. Pendentives are one such solution, squinches are another. Pendentives are simpler in appearance, but more complex in their geometry.

However, be well aware that there is a great range of constructions to solve this architectural problem, where bands of stone might be decorative or could be structural - is a horizontal band a drum or just prettifying and tidying up, for instance? Here, we endeavour to explain and illustrate the graduations, differences and similarities to be found when looking at pedentives, squinches, drums, domes and lanterns, rather than continuing the verbal hand-waving often to be found, done to to distract from lack of clarity, precision, or knowledge.

Pendentive

Pendentives are concave, triangular segments of a sphere, reminiscent of a sail. Being inverted triangles, they taper to a point at the base and spread at the top. Thus, the upper side of the four pendentives together are a major part of the continuous circular base needed to support a dome above a square room.

Architectural definition of pendentive: one of the concave triangular members that support a dome over a square space.

[Etymology: used from early 18th century. Coming from the French adjective pendentif, -ive, which is derived from the Latin pendent-, pendens (‘hanging down’). Present participle of the verb pendēre, to suspend.]

Another, earlier solution to the transition between a square base and a round or octagonal upper part is the squinch, a wedge of masonry, often hollowed-out, filling in the corner space at the top of the square walls and below the base of the dome or drum.

Squinch Squinch

A squinch is an architectural construction that built across an interior angle of a square room to become part of a base for supporting an octagonal or hemispherical dome. There are several construction methods and styles. .

Squinches may be formed by masonry built out from the internal angle in corbelled courses, by filling the corner with a cone placed diagonally, or by building an arch or several concentric arches extending outwards across the corner.

Translated from Viollet Le-Duc: Squinch stacked wedges, having the shape of a shell, that are used for corbelling. The builders of the Middle Ages made great use of squinches to carry eight-pointed stone spires on square towers, watch-towers on the facades, corbelled turrets; they used squinches instead of pendentives to build cupolas on doublet arches resting on four piles.

- Pilaster

- shallow, rectangular pillar attached to a wall. A pilaster is not load-bearing, it is a decorative addition to a wall.

On the other hand, an engaged column

is a curved shaft built directly into a wall. It is like any other column, but it is physically connected to the wall, being a part of it. An engaged column is load-bearing, helping to hold the ceiling as well as providing support buttressing to its surrounding wall.

- Pillar, column, pier.....

- Here, I am following the definitions and descriptions of Viollet Le-Duc. I shall treat columns and pillars as not being the same thing, in that I take pillars to be composite and part of the Gothic structural innovation.

All of these are upright posts of various heights, thicknesses, and so of differing substance.

Then you can also read of posts, struts and stanchions! Here we will look only at pillars made of stone.

The words pillar, column, and pier are interchangeable, but some like to use them more specifically as the following illustrates:

• Pillar - a large, vertical post or similar tall structure, often used for supporting a building or parts of it.

• Column - An upright pillar, usually a cylinder, designed usually to support a larger structure or part of a building above it, such as a roof or horizontal beam, but sometimes used for decoration.

• Pier - one of the pillars supporting a bridge or arch, a rectangular pillar or similar structure that supports an arch, wall or roof, a large column, or a squat or short one.

Because columns are of relatively small diameter, they are only capable of supporting limited vertical down force and unable to support much oblique load, like those generated by arches or vaulting.

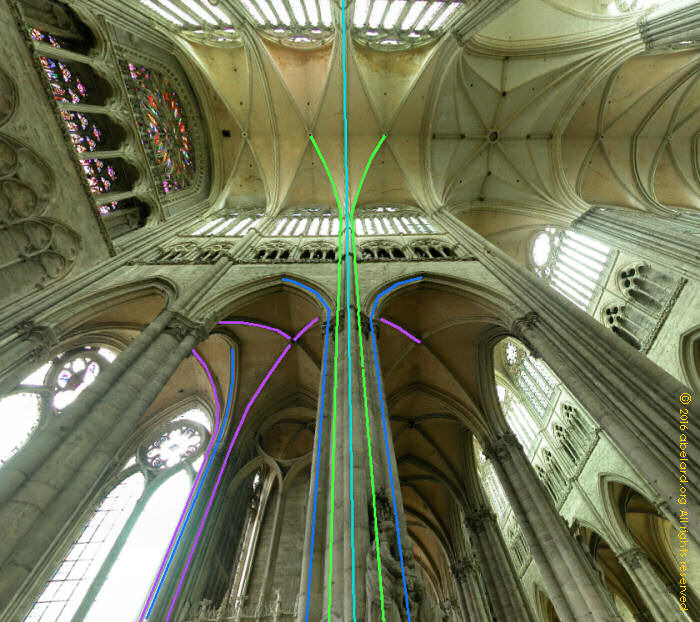

Composite or compound pillars have one part that rises and supports a lower arch, while another part continues higher to, say, support an arch or some vaulting. A pillar is made up of a principle support, with several subsidiary shafts and half-columns (or responds). In the photograph below, the various component pillars are coloured to show which higher parts of the cathedral's structure are being supported. Only one compound pillar has been marked (to the left of centre, with two purple lines enclosing a blue line). You can follow similar paths on other pillars to see how they contribute to this support of the cathedral's ceiling. |

Illustrating complex/composite columns at Amiens cathedral: south transept, facing west

Illustrating complex/composite columns at Amiens cathedral

Key for illustration to the left

cyan: supporting transept main vaulting.

green: supporting diagonal ribs of main vaulting

blue: supporting arches

purple: supporting diagonal ribs of lower vaulting

|

|

|

- While composite pillars are designed to look as if each arch is supported by its own separate pillar, this is a clever optical illusion. The cross-section above suggests how each smaller pillar is part of one of the wedges making up the pillar, fitted together like cheese wedges. When they did not reach the centre of the main pillar, the central space could be filled with rubble. But note that these construction details are only suggestions.

Of course, unless the pillar is taken apart, no-one can be sure what the masons did, including whether there is a central cavity, and if so, was it filled with rubble. However, the result is the appearance of being a separate main column surrounded by smaller columns, supporting one arch or rib above.

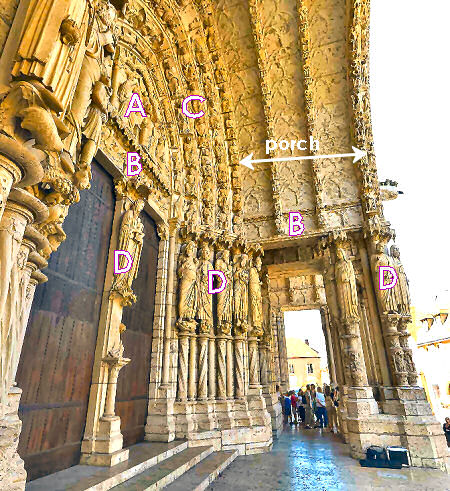

- Porch

- The part of a portal that extends outwards beyond the cathedral portal, its extrados. The archivolts of the porch are supported by statuary and a lintel.

-

Portal and porch labelled (at Chartres cathedral, north transept, east side)

A : tympanum

Portal and porch labelled (at Chartres cathedral, north transept, east side)

A : tympanum

B : lintel or architrave

C : archivaults

D : statuary (the statue between the doors is a trumeau)

- Portal

- The ensemble of a cathedral door, its surrounding statuary, lintel, typanum and archivaults.

See image just above [Porch.].

- Prince-bishopric

- When a bishop (or archbishop) held one or more

secular titles concurrently with their religious

office, their title was prince-bishop and their

religious domain was called a prince-bishopric.

As well as being a bishop or archbishop, they may

have been a prince (or other powerful person, like

a duke) of a local secular territory (which for

a prince was called a principality). The secular

territory may be coincident partially or totally with

their diocesan jurisdiction.

- Quire

- The Quire (as distinct from the Choir) is an area of the church often referred to as a “chancel”.

paper is normally sold to the consumer in reams or quires and commercially in bundles, bales and more recently pallets. In modern times the ream has become standardised at 500 sheets and the quire at 25 sheets. A quire is an old-fashioned term for four sheets of paper folded to make 16 pages.

- Quadrapartite vaulting

- a vaulted ceiling with four ribs.

For much more technical detail, see Sexpartite vaulting.

[For illustration, see Net.]

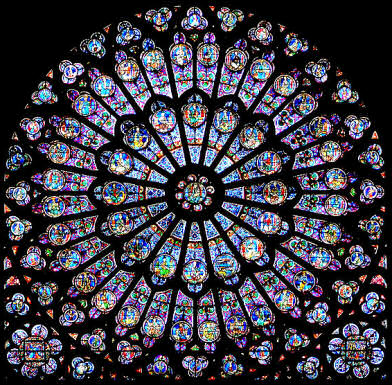

- Rayonnant

-

rayonnant rose window, south transept, Notre Dame de Paris

Here, the glass is constructed as rays spreading out from the window's centre. In the example above, the rays mimic lancet windows. Such windows can be seen in the south rose at Laon, the south rose at Rouen cathedral, and also the north rose of Ouen Abbey Church in Rouen.

- Respond

- Half-pillar attached to a wall to support an arch, or the rib of a vault. (Can also be an half-arch). [illustration]

- Retable or reredos

- A retable is a vertical construction placed either on the altar or immediately behind and attached to it, so forming a large decorative backdrop; usually

highly gilded and often highly decorated with paintings, statues

and other carvings. [illustration]

There are many, confusing definitions of a retable, some of which

make an apparent separation of whether or not the backdrop to a church's main altar is attached to the altar. According to more recent, probably English, church historians, a reredos is

a decorative screen above and behind the high altar, but structurally separate from it. However, it is unclear as to whether there is, in fact, any actual difference between this and a retable. Certainly, Viollet Le-Duc's Dictionnaire only has an entry for the retable.

-

-

- Retrochoir

- Found in churches built after Gothic times, when the main (high) altar was moved westwards to, say, the transept crossing level. Portion of a large church behind the retable or reredos of the high-altar, in apsidal arrangements including parts of the north and south chancel-aisles on either side as well as the area to the east. It is essentially the volume bounded by the sanctuary and the chapels to the east.

From Latin, retrochorus - behind the choir.

-

-

-

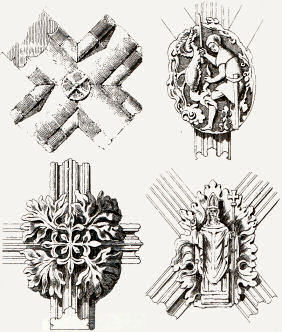

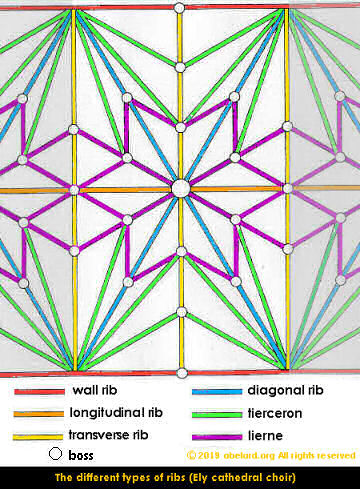

- Ribs and bosses

-

Ribs are part of the structure of

the vault.

Curved columns of piped masonry, the ribs outline the armature [framework] of the vaulting.

[See Net.]

Particularly in England, where the perpendicular style developed, ceilings became far more decorative and complex. Ribs tend to be categorised with various labels including longitudinal, traverse, diagonal,

tierceron (in-between rib, from O.Fr. tiers, tierce; L; tertia - a third),

lierne (linking rib, prob. from M. Fr. lier - to bind; L. ligare - to tie).

Tierceron and lierne ribs are primarily decorative, not weight-bearing.

Very fancy ceilings (decoration) are often referred to as fan vaulting - variations of cones.

This part of the cathedral or church you will often hear called the roof, but it is not the roof, it is a ceiling.

|

|

The joins between various ribs were usually covered by bosses of various artistic merit and complexity. Such bosses can be seen in Norwich, Exeter, Ely, Winchester, Hereford, King's College Chapel Cambridge, Gloucester, and many other cathedrals. Even fancier pendant vaulting can be seen at Canterbury and at Westminster. The bosses were, in part, used to cover the joins between ribs, but also developed as an art form. These bosses have lasted rather better than much English church art, as the vandals of Henry VIII and Cromwell were less able to get at them. In Norwich, there are over 150 bosses, often highly coloured. |

- Roman arch

- See Arches and vaults

- Rood screen

- Also known as choir screen, chancel screen, or jube (un jubé).

An ornate stone or wood partition dividing the nave from the choir.

- Roof

- See Forest

advertisement

- Sacristy

- Small room, usually leading from the east end of a church, used by the priest to don his ceremonial vestments and prepare for a service. Also used from counting up moneys donated.

- Safe room

- Imitated in current times, this room of last resort was constructed under the eaves, close to the military walkway on high. Safe rooms are often marked by openings in the church wall close under the roof's eaves.

[For more, see Fortified churches, mostly in Les Landes.]

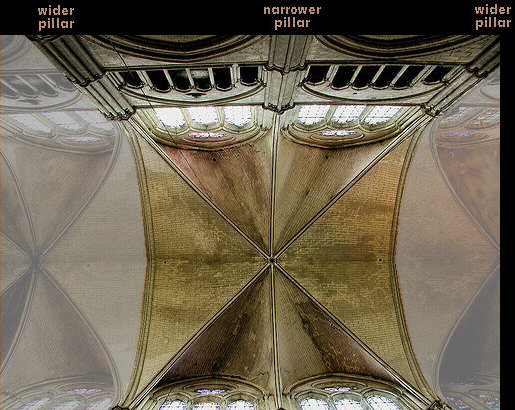

- Sexpartite vaulting

- a vaulted ceiling with six ribs. [See Lyon cathedral.]

Bourges sexpartite roof vaulting.

Credit: AEngineer

Bourges sexpartite roof vaulting.

Credit: AEngineer

“The Bourges sexpartite vault is estimated

to weigh 370,000 kg (820,000 lb), that is approximately

400 imperial tons. Whereas, Mark estimates that the

Cologne quadrapartites to weigh 270,000 kg (600,000

lb), that is going on 300 imperial tons. [Primarily from Mark,

p.115.]

[An imperial (long)

ton is 2,240 lb or 1,016.05 kg.

A short or American ton is 2,000 lb or 907.18 kg.

Increasingly used is the metric tonne of 1000 kg, or 2,204.6 lb.]

Comparing one Bourges sexpartite with two quadrapartites, a Bourges sexpartite covers an area of about 92.2% of two Cologne quadrapartites. Thus, 400 tons at Bourges matches to about (300 tons x 2 x 92.2%), that is 553 tons. You can see from the figures that the sexpartite formation is more efficient in supporting and spreading the load than the quadrapartite configuration [Abstracted from Mark, p.117, note 15].

The

vaults also have rubble, or fill, to increase pressure

and to help stabilise them. This included in the weights

quoted. Mark estimates that the horizontal outward thrust

on the main piers as 28,100 kg (62,000 lb) at Bourges,

and 31,300 kg (69,000 lb) at Cologne. The secondary,

lighter pier at Bourges, Mark estimates at 11,300 kg

(25,000 lb).

- Side aisles

- These can sometimes be double.

- The space between four pillars is called a bay or

a transverse section. The vaulting goes diagonally across

between the piers of each bay.

- Socle

- The socle is the first row of stones above the base, in a wall, or a pillar, or a column. The base always provides emphasis to the projection just above, a more or less pronounced thickening or broadening - the socle. In the

constructions of the Middle Ages,the profile of the projecting socle was never left horizontal. In Romanesque architecture, the

profile that crowns the socle is usually a bevel 45º to 60º. Later, during the Gothic period, the profile of the socle

was often a moulding (bead) carved so as not to present sharp edges that could injure passers-by. There is no need to say that

for socles, the builders of the Middle Ages have chosen the toughest materials.

A socle is a type of torus that is at times decorative as well as functional (helping to spread a pillar's weight.)

[Derived from Viollet Le-Duc.]

Definitions of socle by others are often sloppy :

lower panels of a portal, or

stone carving on which a statue stands, such as a lion, donkey, angel, book.

Etymology: French; from Latin socculus, probable diminutive of soccus - a sort of shoe or slipper (related English word, sock). Also possibly Italian zoccolo - wooden shoe".

-

- Spandrel

- Triangular-shaped area of stone between two arches that are in a row. Below, the spandrels are highlighted in pink. Spandrels may be decorated with diapers, as in this illustration.

Part of the south transept at Westminster Abbey, England, showing spandrels with diaper decoration.

[1870 lithograph]

For three-dimensional spandrels see fan vaulting: an English phenomenon.

- Spolia

- Reused material. Rubble, or fill, used to increase pressure

on vaulting and to help stabilise them. [See sexpartite vaulting.]

Reused old glass is also sometimes referred to as spolia.

-

- Springer, springing, springing point, spring

- Occasionally, you will see terms like"springing from" and "springer". They all refer to where the arch arises from a pillar. In particular, the first stone is called the springer. The top, central stone of an arch is called the keystone. The top stone of a pillar is called the capital.

Springers are the first, the lowest, stones of a vault rib or arch above the springing point

(the level at which a vault or arch rises from its supports, such as pillars). In Gothic vaulting, it is the lowest stone of a diagonal or traverse rib.

The spring, or spring line, is the horizontal line drawn across and joining the two springing points of an arch, these being at the junction of the vertical face of the impost with the rising intrados.

- Squinch

- A squinch in architecture is a solution to the structural problem of making the transition from a square room supporting an octagonal or spherical dome above it. Another solution to this structural problem is the pendentive [See Pedentives, squinches, drums, domes and lanterns for illustration and further discussion.]

- Stilted arch

- See Arches and vaults

-

|

- Story window

Stained glass window which tells a story, from the Old or New Testament of the Bible, or the life of a saint. Stained glass window which tells a story, from the Old or New Testament of the Bible, or the life of a saint.

abelard.org has made a detailed

analysis of the story window of Saint Julian the hospitaller in Rouen cathedral.

[key to the story panes in the St Julian the Hospitaller window]

- Talus

- The talus, a sloped portion at the base of a fortified wall, provided an effective defence in several measures.

• Conventional siege equipment was less efficient against a wall with a talus.

• Scaling ladders may be unable to reach the top of the walls and the ladders were more easily broken because the large angle of slope caused bending stresses.

• A Siege tower could not approach closer than the base of the talus, with its gang plank often unable to reach across the horizontal span of the talus, making them useless.

• Defenders could drop rocks over the walls, shattering on the talus and spraying stone shrapnel at attackers at the base of the wall.

[See Fortified churches, mostly in Les Landes.]

- Tamboret

- Literally, a stool, a multi-legged seat without a back or arm supports.

In the context of a cathedral building, a plinth, a support for a large structure such as a spire, made so the congregation and visitors can walk underneath the supported structure.

[see Notre-Dame de Paris: four years after the fire]

-

- Thurible

- Censer of incense [see Le

Mans cathedral]

- Torus

- A ring, often like an inflated inner tyre or a doughnut.

- Tracery

- Tracery is a decorative method of providing the stone framework, and so the support needed, in windows of great spans. Tracery can also be found in rose windows Stone tracery is also a common form of decoration in towers, as chapel dividers, and even garden walls, where glass is not inserted. Similar patterning appears with other materials, such as wood.

See also Stone tracery in church and cathedral construction.

-

- Transept

- Going across the main body of the cathedral, with north and south arms, sometimes with side doors. See cathedral plan.

- Transom

- a strengthening crossbar, in windows or above a door.

[See transoms for illustration and further discussion.]

-

-

- Transverse arch

- Supporting arch which goes across a longitudinal vault, from one side to the other, and so divides the bays in a side aisle. A traverse arch usually projects out and downwards from the surface of the vault.

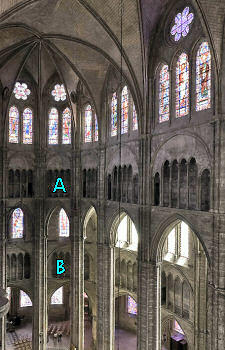

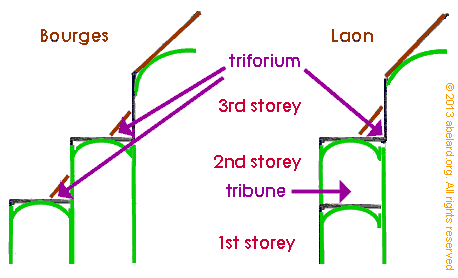

- Tribune

- A tribune is a much

wider area than a triforium, extending across the width of the aisle below.

The tribune is more like a room, lit by windows to the outside. Also known as a gallery.

-

- Triforium

- The word triforium has no reliable etymology,

but has come to mean the arcaded gallery below the clerestory windows and

above the nave aisles and side bays. More effectively, I would use triforium as describing a minor gallery somewhere above the nave aisle level. This word was first used by Gervase of

Canterbury, c. 1185, to refer to a gallery at Canterbury

Cathedral, and was used only in the context of Canterbury

Cathedral until about 1800.

|

|

Bourges cathedral

A: Upper triforium; B: Lower triforium |

Four colonnade levels at Laon cathedral

Image credit: Michael Leuty |

simplified schematic showing the relationship between the pillars, aisles, triforia, tribunes and roofs

in Bourges and Laon cathedrals |

Bourges cathedral has two

walkways [A and B] between the upper, middle and lower rows of stained glass windows. On the

external view of the cathedral, these triforia are beneath a sloped roof protecting them as

the roof extends outwards beyond the row of windows above.

The technical term for such a walkway is triforium. But

beware, there are columned walkways that look rather similar but which are called tribunes.

What’s the difference? The triforium is a relatively narrow walkway without windows. The

triforium and the outside roof hide the space above the vaults. In that space, rubble was placed to to increase

pressure and so to help stabilise the vaults below. The triforium also provides another

row of colonnades and so contributes to the coherence of the cathedral interior.

Notice that the triforia come opposite protective roofs on the outside.

This hiatus is the meeting between levels of aisle arches. You can see a tribune glazed at the

second level between the low-level windows and the clerestory at Laon - see the two cathedral cross-sections above. The triforium does not have a

walkway in some cathedrals, or parts of cathedrals. In this case, it is often referred to as a

blind, or false, triforium. [Le Mans/Bourges]

There are one or two glazed triforia, for example at Tours and at Saint-Denis, Paris, the latter being often regarded as the first of the true Gothic structures.

|

|

| Part of the triforium level at Tours cathedral |

In the Tours triforium walkway |

Trumeau- A pillar statue, for example between porch doorways. Traditionally, the person represented on the trumeau is the person after whom the door is named.

See Noyon cathedral.

- Tympanum (in French, tympan)

- the half-moon shaped space above the exterior doors of a cathedral, shaded by the archivaults above. The tympanum often illustrates events in the life of Christians, or events in the Bible or in the life of a saint. A Latin word, the plural is tympani.

[For illustration, see Porch.]

advertisement

- Vault

- See Arches and vaults

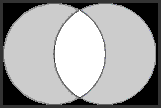

- Vesica, mandorla

- Literally, a bladder. In stained glass, an ovoid shape with pointed end. Sometimes referred to as almond-shaped.

A vesica can be constructed from two intersecting circles with the same radius.

- Vestery

- You will sometimes see a section beyond the choir and east of the altar, or in other positions, labelled as the vestery. This is a moveable feastand refers to where the priest and his assistants dress or change before and after services.

- Voissoir / voussour / voussure

- An arch is built of voissoirs, or stones shaped like wedges. The voussoir at the top and centre of the arch is the keystone.

See claveau.

- Volute

- A spiral scroll, usually part of the decoration on a capital.

advertisement

|

Bibliography

|

Experiments in gothic

structure by Robert Mark

MIT Press

pbk 0262630958

reprint: 1984 amazon.com / amazon.co.uk |

|

Fan vaulting: A study of form, technology, and meaning

by Walter C. Leedy, Jr. |

|

Arts + Architecture Press, pbk, California, 1980

ISBN-10: 0931228034

ISBN-13: 978-0931228032

amazon.com

amazon.co.uk |

|

|

The Gargoyles of Notre-Dame: Medievalism and the Monsters of Modernity by Michael Camille

University Of Chicago Press, hbk, 2009

ISBN-10: 0226092453

ISBN-13: 978-0226092454

amazon.com / £30.88 [amazon.co.uk] {advert} |

|

|

Dictionnaire raisonné de l'architecture française du XIe au XVIe siècle by Eugène Viollet Le-Duc.

abelard.org regards Viollet Le-Duc as definitive for architectural terms. Definitions from other sources are often inconsistent. |

|

|

A Dictionary of the Architecture and Archaeology of The Middle Ages Including Words Used By Ancient And Modern Authors

by John Britton |

Longmans, Orme, Brown and Longman

London,1838, hbk |

Reprint, pbk

University of Michigan Library

ASIN: B002ZVOO9U

$41.99 [amazon.com]

amazon.co.uk |

|

|

An Introduction to Gothic Architecture

by John Henry Parker

Parker and Co, hbk, 1891

ASIN: B001J2E2GG

amazon.co.uk |

|

|

Gothic Architecture -

An Attempt to Discriminate the Styles of English Architecture from the Conquest to the Reformation

by Thomas Rickman

Parker and Co, hbk, 7th edition, 1877 |

reprints:

Forgotten Books, hbk, 2017

ISBN-10: 0331825511

ISBN-13: 978-0331825510

$27.84 [amazon.com]

£23.91 [amazon.co.uk] {advert}

Cambridge University Press, pbk, 2013

ISBN-10: 1108066429

ISBN-13: 978-1108066426

$23.92 [amazon.com]

£16.99 [amazon.co.uk] {advert} |

|

|

Les

Vandales en France, 1914, 1915

L’Art et les Artistes,

1915 |

|

|

|

The Cathedral

of Reims - the story of a German crime by

Maurice Landrieux, Bishop of Dijon; translated by

Ernest Williams

Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd., London,

1920

Lightning Source UK Ltd, 2010

ISBN-10: 114320803X

ISBN-13: 978-1143208034

$23.37 (amazon.com)

£18.99 (amazon.co.uk) |

|

advertisement

end notes

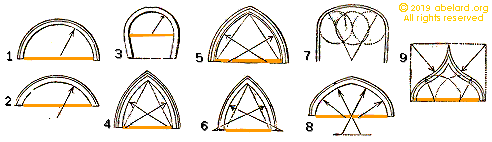

- Arches are round pointed or mixed.

A semicircular arch has its centre in the same line with its spring [line], [as in fig. 1 below.]

A segmental arch has its centre lower than the spring, [as in fig. 2.]

A horse-shoe arch has its centre above than the spring, [as in fig. 3.]

Pointed arches are either equilateral, described from two centres, which are the whole breadth of the arch from the other, and form the arch about an equilteral triangle,[as in fig. 4;]

Or drop arches, which have a radius longer than the breadth of the arch, and are described about an obtuse-angled triangle, [as in fig. 5;]

Or lancet arches, which have a radius shorter than the breadth of the arch, and are described about an acute-angled triangle, [as in fig. 6.]

All these pointed arches may be of the nature of segmental arches, and have their centres below their spring.

Mixed arches are if three centres, which look nearly like elliptical arches, [as in fig. 7;]

or of four centres, commonly called the Tudor arch; this is flat for its span, and has two of its centres in or near the spring, and the other two far below it, [as in fig. 8.]

The ogee or contrasted arch has four centres; two in or near the spring, and two in or near the spring, and two above it and reversed, [as in fig. 9.]

[From An attempt to discriminate the styles of architecture in England, p.46]

- triforia

- Triforia is the plural of the Latin word triforium. In Latin, words that end in -um are most often neuter words in the Second Declension, and decline (change) to -a in the plural.

Many will remember declining bellum - war:

Bellum, bellum, bellum, belli, bello, bello

Bella, bella, bella, bellorum, bellis, bellis.

Of course, this degenerated in schoolboy/girl fashion

to

B’lum, b’lum, b’lum, b’li, b’lo,

b’lo

B’la, b’la, b’la, b’lorum, b’lis,

b’lis!

So - one triforium, several triforia.

- Composite is often used to describe an object made by combining two different materials, such as steel and cement, or two different grades of material.

Composite is also used to describe a particular type of capital to a column that combines elements of the Corinthian and Ionic-style capitals.

- sarrancolin

Sarrancolin is a multicoloured marble extracted in the village of Sarrancolin, in the Hautes-Pyrénées department. The quarries were exploited extensively under the reign of Louis XIV, and from 1692 they were considered "royal quarries". The Sarrancolin marbles generally feature a light background patterned by reddish veins and grey/green intrusions. This marble is also known as Fantastico, Opera Fantastica, Opera Fantastico, Opera Fantastique, Rosaire.

-

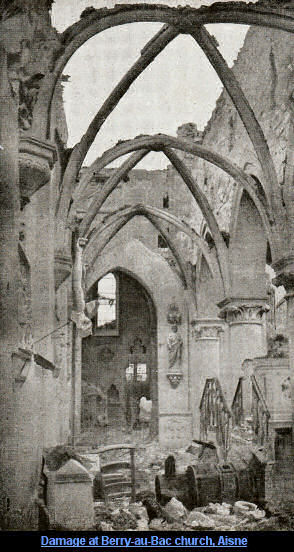

Vault ribs - necessary or decorative? Vault ribs - necessary or decorative?

It was long thought by some that ribs supported the vaults. Modern analysis, for instance Mark (chapter 8), have questioned this dogma.

1. This should be obvious from the many vaults that do not have emphatic

ribs right from the early development of groin vault.

2.

The stresses are probably better thought of as an egg-shell, where the strength is inherent in the structure, and the stresses are distributed around the structure. The weight eventually is eventually transmitted down to pillars. The effect is well seen in the World War One photograph of damage to Reims cathedral.

Although it is possible that the early builders could have believed that the ribs were a structural necessity, it could as easily have been decorative, or have been helpful in building the structures (over wood formers). The actual stonework suggests that the ribs and net are built into each other, which is in accord with the modern view that at most the ribs are structurally part and parcel of the vault, not some separate structural function.

While the ribs are probably of little relevance in the stress distribution within the eggshell of the net, the ribs do appear to be stronger than the rest of the net when under heavy stress. Here, to the right, is an example of the result of the heavy shelling of religious buildings by the Germans during the First World War.

|

Buttresses are stone

bracings that prevent cathedral walls collapsing from lateral and vertical pressures. As well as

the weight of the roofs and walls, pressure can come from winds pushing against these tall and

bulky structures.

Buttresses are stone

bracings that prevent cathedral walls collapsing from lateral and vertical pressures. As well as

the weight of the roofs and walls, pressure can come from winds pushing against these tall and

bulky structures.

Pendentives are one such solution, squinches are another. Pendentives are simpler in appearance, but more complex in their geometry.

Pendentives are one such solution, squinches are another. Pendentives are simpler in appearance, but more complex in their geometry. Squinch

Squinch