|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

Germans in France -saint quentin cathedral [basilique] |

|

|

|

|

||

|

Gustave

Eiffel’s first work: the Eiffel passerelle, Bordeaux a

dream unfulfilled - the transporter bridge [pont transbordeur],

Bordeaux Ile

de France, Paris: in the context of Abelard and of French

cathedrals France’s western isles: Ile de Ré France’s western iles: Ile d’Oleron Marianne - a French national symbol, with French definitive stamps the calendar of the French Revolution Pic

du Midi - observing stars clearly, A64 Carcassonne,

A61: world heritage fortified city the

forest as seen by francois mauriac, and today mardi gras! carnival in Basque country what a hair cut! m & french pop/rock country life in France: the poultry fair short biography of Pierre (Peter) Abelard

|

During World WarOne, Germans occupied the city on 28th August 1914. Following this, there were many battles with Allied troops fighting in this locality during 1914, in 1917, and twice in 1918. One British soldier here was the war poet Wilfred Owen. St Quentin was finally liberated on 1st October 1918. During the German occupation, there were many attempts to dislodge the Germans, resulting in the near total destruction of the cathedral, leaving just the outer walls.

On 15th August 1917, the cathedral was set on fire and by the next afternoon all that was left was the outer walls. German newspapers claimed that the fires had been started by French gunfire. However, the 15th was relatively calm in this region with few bombardments. On the other hand, German troops had been seen pillaging the city of St. Quentin, including their officers being party to wholesale removal of stolen goods, including coal, factory equipment, wine and mattresses (for wool).

By 1918, the cathedral was almost completely destroyed, except the exterior walls.

As you can see in the photograph just above, there are tie-rods high in the springing. (Compare this with Westminster Abbey, of which the tie-rods are positioned where the pillars meet the springing.) These rods allowed tensions to be adjusted as a help in stabilising the building. They existed in both the apse and the nave. In the late 19th century, these tie-rods were removed from the nave. During the war damage, it is noted that the vaulting still held up fairly well in the nave, while it collapsed in the apse. The damage to the cathedral was considerable: not only the vaulting of the apse had collapsed completely, the flying buttresses were partially destroyed, there were numerous breaches in the walls and buttresses, while some masonry threatening to collapse could precipitate large falls, and the state of the bell tower was particularly worrying. After the war, the Basilique de St. Quentin was restored.

The task of restoration was given to Emile Brunet, chief architect of the Historic Monuments Service, sometimes known as “the cathedral man” for his knowledge of ancient building techniques. At first, German prisoners of war cleared about 3,000 cubic metres of cut stone and rubble. Unfortunately, not being adequately supervised, they further damaged carvings and decorations. The most urgent consolidations of masonry was done by specialised workers, parts from damaged sculptures being put aside carefully for later restoration. In order to protect the stone of the building from the weather until the roof was replaced, a temporary framework of eaves was placed on the top of the remaining walls, onto which 5,000 square metres of fibro-cement and Ruberoid sheeting was spread. The restoration took twenty-five years. |

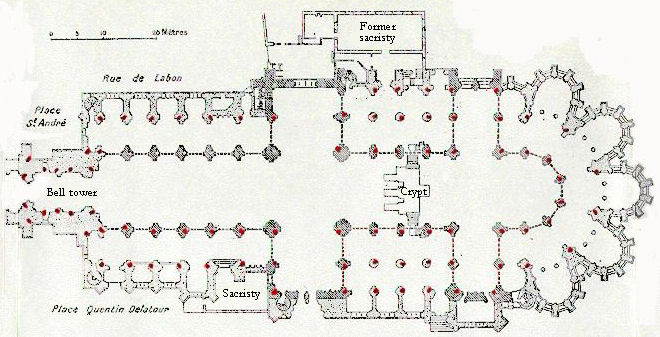

Floor plan of the Basilique de St Quentin, drawn by Emile Brunet. The red dots mark 93 bore holes made by the Germans for holding explosives in order to destroy the building. |

|

|

the labyrinth ('maze')The Basilica of Saint Quentin has a labyrinth. The labyrinth at Amiens is somewhat similar. (Much more information on this at the Amiens link.)

|

© abelard, 2010, 29 May the address for this document is https://www.abelard.org/france/germans_in_france-stquentin.php |