France - île de la cité, Paris:

in the context of Abelard and of French cathedrals

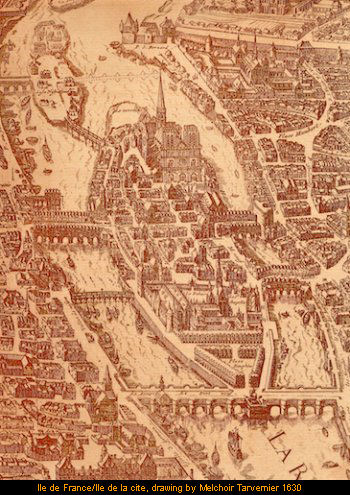

In the time of Pierre Abelard, the Île

de France - which is now known as the Île de

la Cité - was a small, growing centre of the rising

power of Paris. This eventually developed to become France.

This page a companion and background to the cathedrals

section and the section about Abelard.

Virtually nothing remains of the original Île de

France from the time of Abelard. There is just a small

section in the Cluny Museum. In fact, very little of Paris

extends back to Abelard. There is an abbey tower across

the river, and that’s about the lot.

Notre-Dame cathedral, in the photo below, was started

after the death of Abelard, replacing an earlier cathedral

dedicated to St. Stephen (St. Étienne). That cathedral

extended forty metres forward of the west front of the

modern cathedral. It was narrower than the present structure.

I believe that the old cloister where Abelard would have

taught is probably on the north side and to the north

of the current cathedral. The island was, essentially,

divided between church and state, with the church at the

eastern end of the island where the cathedral now lives.

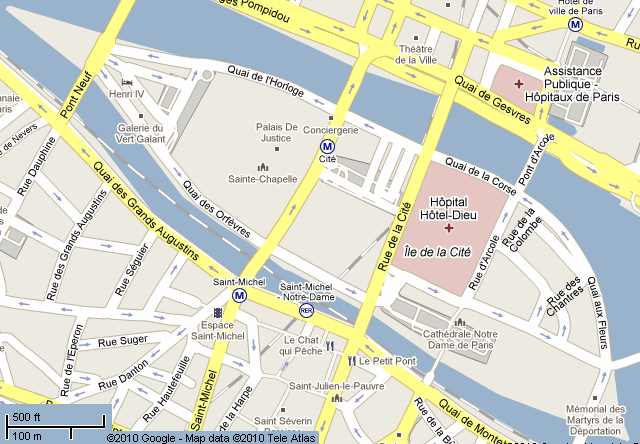

Google map of the Ile de France, Paris

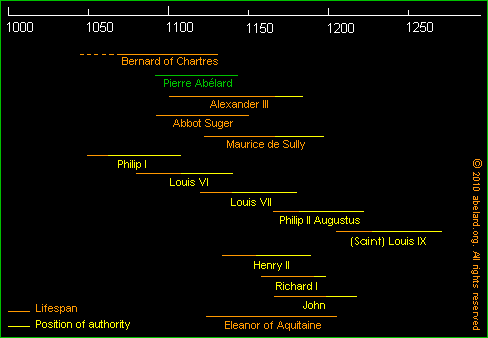

contextual dates contextual dates

- Bernard of Chartres (Bernardus Carnotensis) died c. 1130

- Pierre Abelard: 1079-1142

- Pope Alexander III: c. 1100/1105-1181

- Bernard of Clairvaux: 1090-1153

- Abbot Suger, founder of St. Denis: circa 1081-1151

- Maurice de Sully, founder of Notre-Dame: c. 1120-1196, bishop of Paris, 1160-1196

- 1140: Dedication of Saint-Denis

- 1160: Notre-Dame foundation stone laid by Pope Alexander III

- 1248: Sainte-Chapelle construction finished

- 1250: Notre-Dame mostly complete

- Philip I: 1052-1108; King of France: 1060-1108

- Louis VI [Le Gros: the fat]: 1081-1137; King of France: 1108-1137

- Louis VII [Le Jeune: the young]: 1120-1180; King of France: 1137-1180

- Philip II Augustus: 1165-1223; King of France: 1180-1223

- Louis IX [Saint Louis]: 1214-1270; King of France: 1226-1270

- Henry II: 1133-1189; King of England: 1154-1189

- Eleanor/Aleinor of Aquitaine: 1122-1204. She first married Louis VII, then Henry II, mother of Richard and John

- Richard I [the Lion heart]: 1157-1199; King of England: 1189-1199

- John [Lackland]: 1167-1216; King of England: 1199-1216

If you look at this chart, you will see that the French

kings invented a marvellous way of becoming important.

They managed to rule for unusually long periods. The Angevins

(or Plantagenets) had spent several generations marrying

the right people. This culminated in Henry II, an immensely

effective ruler who dominated the western half of France,

holding it against his weak Capetian rivals.

Meanwhile, as you see in the chart, the great innovators

on the Ile de France were building the intellectual hothouse

of Europe.

But Henry II had a fatal flaw. His child-raising skills

left much to be desired. So when Richard I took over,

he was far more interested in adventure and becoming one

of the greatest generals of all time. In the end, this

got him killed. Poor John tried his damnedest to hold

together the huge empire his father had built, but those

pesky French kings with their long experience steadily

outmaneuvered the Angevins and their successors, slowly

eroded the Norman grip in what is now France.

You might surmise that, if you were an English nationalist,

that it was the French who were better at being perfidious,

or you might call it crafty.

the

cathedral of notre-dame and its predecessor, the basilica

of st. étienne

The basilica of St Etienne existed for about six hundred

years before Maurice de Sully, the new bishop of Paris,

decided to raze the dilapidated building and construct

and much bigger and more beautiful edifice, dedicated

to Our Lady.

Church administrative offices, student accommodation,

cloisters and the nascence of the University of Paris

grew out of this melee to the north of these cathedrals.

Today, this area comprises small roads, such as

- Rue Chanoinesse

- Rue d’Arcole

- Rue de la Colombe

- Rue des Chantres

- Rue Massillon

- Rue des Ursins

- Rue du Cloître-Notre-Dame

|

advertising

disclaimer

on first

arriving in France - driving

France

is not England

Marianne

- a French national symbol, with French definitive stamps

the

calendar of the French Revolution

la

belle époque

Grand

Palais, Paris

the

6th bridge at Rouen: Pont Gustave Flaubert,

new vertical lift bridge

Futuroscope

Vulcania

Space

City, Toulouse

the

French umbrella & Aurillac

the

forest as seen by francois mauriac, and today

places

and playtime

roundabout

art of Les Landes

50

years old: Citroën DS

the

Citroën 2CV:

a

French motoring icon

Pic

du Midi - observing stars clearly, A64

Carcassonne,

A61: world heritage fortified city

Hermès

scarves

bastide towns

mardi gras!

carnival in Basque country

what a hair

cut! m & french pop/rock

country

life in France: the poultry fair

|

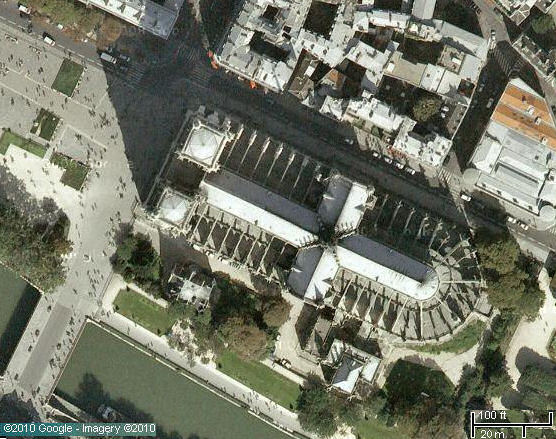

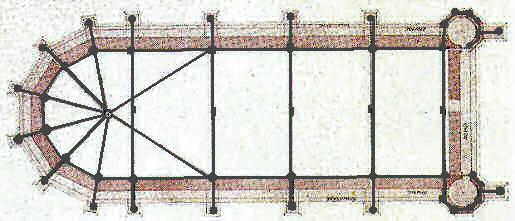

Satellite view, cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris. Image: google.com

Larger scale satellite view of the cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris

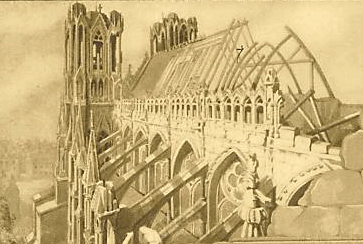

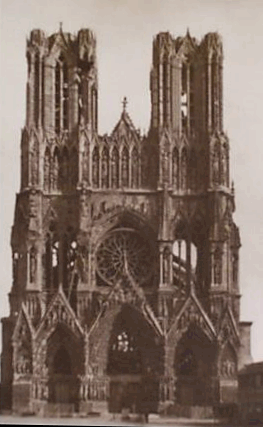

1160: The foundation stone for the vast new Gothic cathedral

of Notre-Dame was laid by Pope

Alexander III on a visit to Paris

1250: Cloister portal to the north completed

1345: Construction completed

Notre-Dame is

one of the earliest

gothic cathedrals, constructed as a very solid, stolid

building, as gothic cathedrals go. However, the problems

were still not worked out fully and some structural weaknesses

occured, especially in the south transept. By the time

the builders were working on Reims, experience allowed

the building of an even more solid structure. So much

so that the main building of Reims cathedral even withstood

the vandalism of the German

batteries in the First World War. It is said that

Reims cathedral was hit by an estimated 1,700 missiles.

[Reims cathedral is thus almost entirely a modern restoration

job.]

|

|

| Reims cathedral after bombing |

As the form developed and experience was gained, the

builders realised that between the pillars there was very

little load-bearing. The structures then became increasingly

ambitious, and ever more airy and light-filled. This development

can be appreciated in the nearby Sainte-Chapelle,

started less than a hundred years later.

dimensions

of Notre-Dame de Paris

- Total length: 130 m/427 ft long

Transept length: 2.25 m/14 ft

Choir length: 11 m/36 ft

Total width: 48 m/158 ft wide

Height of roof: 43 m

Height of vault: 35 m/115 ft

Height of side aisles: 3 m

Height of spire: 96 m

Height of twin towers: 69 m/226ft

Lancets: over 16 m/50ft high

- South tower great bell:

- 13 tons, with 500kg clapper, tolled only on ‘solemn’

occasions

- Total floor area: 4,800 m²

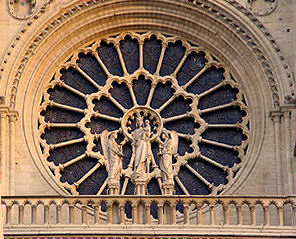

Diameter of north and south [transept] rose windows:

13.1 m/42½ ft

Diameter of west rose: 9.70 m

1,300 oaks, representing 21 hectares of forest, were

used in the timbers and woodwork.

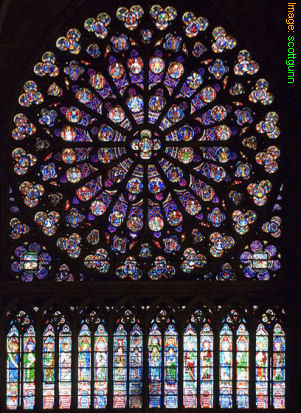

the

south rose

|

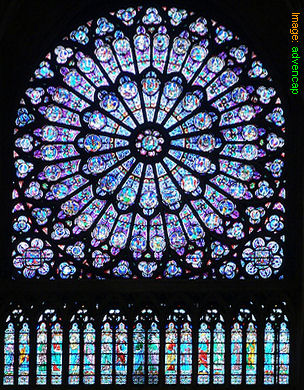

The South Rose or Rose

du Midi was a gift from Louis IX. The structure

of the facade has been broken at least twice. The

whole facade was not built well and so was shored

up since 1543.

The facade was further damaged by a fire during

the 1830 Revolution, when Louis-Philippe of the

Orléans dynasty overthrew Charles X of the

Bourbon dynasty.

As a result, another reconstruction was made from

1861. To counteract the sagging masonry, the rose

was rotated 15 degrees so a load-bearing spoke was

in the vertical, and the facade rebuilt.

Later, in the 1880s, the glass was also repaired,

when the cohesive imagery and design of the stained

glass was scattered as the restorer randomly filled

gaps with salvaged medieval glass. |

Beneath the rose is a row of sixteen

prophets in lancet windows. The four cental ‘senior

prophets’ each have an evangelist sitting

at his shoulder, recalling Bernard of Chartres’

words: “If I have seen further, it is by standing

on the shoulders of giants”.

The four senior prophets are Elisha, Ezekiel, Elijah,and

Samuel. The four Evangalists are Matthew, Mark,

Luke and John. |

|

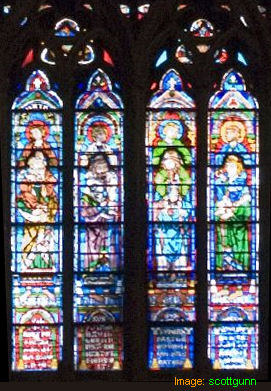

the

north and west roses

|

From the point of view

of the stained glass, the North Rose [to the left]

is probably the best.

The West Rose [below] is the oldest, but restored

to damnation.

It is difficult to see the West Rose from the interior,

organ pipes partially obscure the view. Maybe the restorers can take advantage of the current situation and move the organ elsewhere. However, with 5,266 pipes and 80 stops, this could be problematic. |

The so-called Enlightenment has generated long conflict between the Puritanical factions and the Catholic Church. In 1741, the brothers Leviel substituted "for the priceless [glass of the cathedral] great sheets of dull, monotonous grisaille with borders ornamented with fleur-de-lis ... described by Michelet as le protestantisme entrant dans la peinture [Protestant contribution to painting]."

This was a terrible loss to medieval glass art.

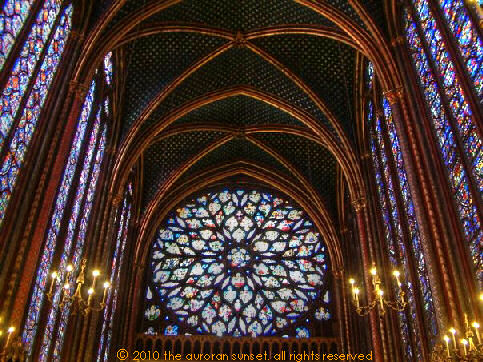

sainte-chapelle

Building of Sainte-Chapelle was finished in 1248, after

an incredibly rapid 33 months of construction. This is

a bit later than the medieval

glass to which I usually attend. But Sainte-Chapelle

is a very special place. Many of the great medieval cathedrals

do not have most of their original glass intact. The overwhelming

exception is Chartres, followed at a distance by Le Mans.

stained glass restoration complete, 20 May 2015:

To commemorate the 800th anniversary of Louuis IX's birth, the windows of Sainte-Chapelle have been cleaned and restored. During an operation lasting seven years, the fifteen, 50-foot high stained glass windows were progressively removed, dismantled into small sections, repaired and cleaned. Lasers were used to remove over 750 years of grime - on the exterior, Parisian coal smoke and traffic pollutions, and inside, candle smoke. The exterior of the windows has then received a protective, transparent glass "skin", while much of the leading, separating and holding the pieces of glass together, has been replacd by transparent resin, to let in more light. It will remain to be seen whether that is a restoration step too far.

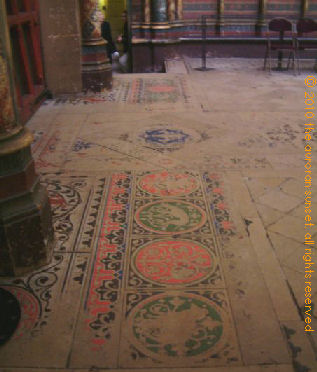

Some of the highly gilded, coloured

and decorated interior of Ste. Chapelle

To me, the great interest of Sainte-Chapelle is that

it has a full complement of glass, produced in the 13th

century and the oldest in Paris, and thus gives an amazing

impression of what could be done by the medieval craftsmen.

While Sainte-Chapelle is a tourist magnet, it is best

to go in off-season, on a weekday, and just find a place

to sit and let the incredible light into your soul. It

is like sitting in the midst of a magic lantern. Not a

place to do too much thinking, but just absorb and absorb.

The church really consists of two chapels, linked by

a spiral staircase. It is the upper chapel that is so

impressive.

This is what churches used to be like, before the more

modern Puritans, destroyers and ‘restorers’

got their hands on them, from Cromwell to Luther to the

French Revolutionaries to various tight-assed puritans

across the continent. In medieval times, churches were

meeting places which hosted markets and great church festivals,

full of colour and life.

15th century Flamboyant rose window surrounded by rich, soaring stained glass

and painted columns

With the thin piers, you will see that the construction

is almost a wall of glass

The glass has 1,134 scenes, with 618 square metres of

glass, forming a veritable illustrated bible.

Added lighting highlights the gilding

|

|

| One of the twelve

statues of the apostles |

Even the floors

are decorated! |

some

notes on the construction of sainte-chapelle

Sainte-Chapelle near the Notre

Dame cathedral in Paris, a fairly small structure,

was built over a period of only five to ten years. It

was put up by Louis IX, in a rush, to house the supposed

relic, the Crown of Thorns,and so Louis IX could race

off on the seventh crusade. Amazingly, Louis had paid

more than three times as much for the Crown of Thorns

than it cost to build Sainte-Chapelle. Note, a reliquary

is the decorated box that holds a sacred relic. The

design of reliquaries has been influenced by church

design, and visa versa. The shrine of Edward the Confessor

in Westminster Abbey is sometimes also regarded as having

a visual reference to Sainte-Chapelle.

Interestingly, the chapel incorporated a form of iron

reinforcement, with two ‘chains’ of hooked

bars encircling the upper chapel, the main part of the

structure. Further, there were iron stabilisers across

the nave (with a vertical tension bar).

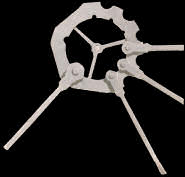

Drawing by Lassus of reinforcing bars, with bars and links emphasised

Also, an impressive eight-pointed iron star helped

hold the apse together. Its iron bars radiated from

a central collar. (The drawings above and below were

made by Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Lassus during the restoration

of Sainte-Chapelle.)

Drawing of eight-ponted iron star by Lassus

Because of the rather dodgy stability of the gothic

buildings, later additions of iron stabilisation can

be seen in many cathedrals, for example in Westminster

Abbey.

![Iron stabilising bars in Westminster Abbey [indicated with blue arrows] Iron stabilising bars in Westminster Abbey [indicated with blue arrows]](/france/culture/cath-cons2.jpg)

Iron stabilising bars in Westminster Abbey [indicated with blue arrows]

Similarly, wooden shoring is not uncommon during the

recent century, while in Sainte Chapelle this innovatory

reinforcement is hidden from sight, incorporated into

the building.

For further discussion, see using metal in gothic cathedral construction.

Sainte Chapelle suffered much during the centuries,

from repeated fires [1630 and 1736] and even flooding

of the Seine [1690]. And then, of course, came the French Revolution, Sainte Chapelle was used

as a flour store, a club room and an judicial archive.

Sainte Chapelle was not handed back to its intended

used for about forty years. After the depredations of

the Revolution, excellent restoration and refurbishment

was supervised by Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Lassus [1807-1857],

and continued by Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc [1814 – 1879].

jules maigret

At the western tip of the island, is the secluded Place

Dauphine, a few steps from the police headquarters where

Maigret had his office. Simenon lived round the corner

and the Taverne Henri IV was his local. The Brasserie

Dauphine was probably the Taverne. Those who enjoy the

Maigret books and its main character may wish to visit

this real-life heart of his fictional world.

For more about Maigret and 'his' books go to

The psychology of Georges Simenon and Jules Maigret -

reviews of all the 79 Maigret novels

|

Notre Dame de Paris, a short history & description of the cathedral, with some account of the churches that preceded it

by Charles Hiatt |

| A useful, if rather scrappy, introduction to Notre-Dame cathedral. |

|

George Bell & Sons, hbk, London, 1902

Sagwan Press, hbk, 2015

ISBN-10: 1298986761

ISBN-13: 978-1298986764

$22.95 [amazon.com] {advert}

£16.95 [amazon.co.uk] {advert}

Forgotten Books, pbk, 2017

ISBN-10: 1330618785

ISBN-13: 978-1330618783

amazon.com {advert}

amazon.co.uk {advert} |

|

|

Les vitraux de Notre-Dame et de la Sainte Chapelle de Paris

by Marcel Aubert, Jean Verrier et al. |

| A wonderfully produced and illustrated catalogue raisonné of the windows of both the churches described above. The book could do with a few more colour plates and with writing in modern language, like English! |

|

Caisse National des Monuments Historiques, hbk, 1959

Corpus Vitrearum Medii Aevi - France, volume I

ISBN-10: x

ISBN-13: x

shipping weight: 2.5 kg/5.5 lb!

height: 32 cm/13 inches

$24.27 [amazon.com] {advert}

£15.99 [amazon.co.uk] {advert} |

|

|

- The inverted v-shaped

accent, called a circumflex, over the ‘I’

of Île, is used in French to indicate a silent

‘s’. Thus the French word ‘Île’

is very closely equivalent to the English word ‘Isle’.

- The name,

Île de France, has changed its meaning from its

orginal sense. Now, Île de France refers to a

region that includes the eight départements of

Ville de Paris, Haute-de-Seine, Seine-Saint-Denis, Val-de-Marne,

Essonne, Yvelines, Val-d’Oise and Seine-et-Marne.

Back in the tenth and eleventh centuries, Île

de France refered to the domain of the Capetians, centred

on the Île de de la Cité. They were often

weaker than other great duchies in France

- The 91.4 metre/300 foot spire reportedly weighed 680 tonnes.

- This 15th

century Flamboyant window of the Apocalypse is a replacement

for a 13th century rose. There is an illustration of

that older window in the Belles Heures [Good

Hours - a illuminated book of hours] of the Duc de Berry.

- A drawing from Histoire archéologique, descriptive et

graphique de la Sainte-Chapelle du Palais by

Alfred Pierre Hubert Decloux and Doury, Paris: Félix

Malteste, 1857.

- Image

credit: Mark

R. Collins

|