|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

fortified churches

|

|

|

|

|

||

The département of Les Landes was a very poor region with a few very rich peasants, riddled by wars, malaria, leprosy and much else. Almost every village has a church, even the very small communities. The church was a refuge in times of strife, and also a meeting place.

The nineteenth century and half of the twentieth was a time of wealth in a large part of Les Landes, thanks to the exploitation of pine resin. In modern times, some places have become richer and over-restored their churches, sticking on a rather tacky spire, while other more down-at-heel communes have left their church nearer its original state to varying degrees. There is a meddlesome enthusiasm for rendering everything accessible is whitewash and plaster. Thus do church decoration and structural elements become lost or buried. It is difficult to find arches clear of such 'enhancement'. Fortunately, these modern vandals always miss something, thus I have found useful examples of naked arches at Taller and Pontonx, and unencumbered exterior walls at Mezos. Some communes have become rich, some poor over the centuries. Without the money, the history and the natural aesthetic have not been wiped out by crude rendering and gross appendages. Thus this page will start with a representative sample of interesting and illustrative churches from around the département of Les Landes. Searching the public records has enabled the uncovering of evidence of the destruction, at that time, of the fortifications of several, particularly interesting churches, which is a real loss for Landes' history of art, study of fortification (castellology), and heritage. resin enriched the département, whilst impoverishing its heritageParadoxically, this prosperity was particularly bad for many Landaise churches. Some communes, at this time, had considerable financial means and were tempted to transform their old church, or destroy it in order to rebuild it, so as to match their new social status. Thus, some churches were destroyed and rebuilt without real necessity, and this destruction was sometimes prevented only by the commune's poverty. Paradoxically, it is in the communes that remained poor at that time that the fortified churches are often the best preserved. An extreme of a rich parish 'upgrading' their historic church is Rion-des-Landes. some historyIn many parts of France, particularly in the south-western regions of medieval conflict, there can be found fortified churches. These were made to provide secure shelter for its congregation and local inhabitants, as well as being a religious meeting place. Some of these churches were built as part of the towns defensive wall, even with the tower being also the town's gate tower as at Montégut [see also Bastide towns: Monpazier, pearl of England and Bastide: Beaumont-du-Perigord]. Based to the great part on shifting sands blown in from the Atlantic that covered mainly sedimentary rock, Les Landes had not much suitable stone available for local land owners and lords to castle build. Thus the churches, which were being built to last, developed the dual roles of religious sanctuary and local fortification to defend and protect the local population. When the very early churches first built, they were built in an era of invasion and attack from aggressors that included marauding pirates, Saracens, heretics and brigands. For instance, in 982, Norman [Norsemen or Viking] invaders were beaten back by the Duke of Gascony's forces, aided by those from Saint Sever. Local lords also employed mercenaries to pillage towns when the lord was not paid. This all gave birth to insecurity. Other threats soon arose with the Franco-English (or Anglo-French) conflicts, then the wars of Religion, and later the Fronde (a series of civil wars between 1648 to 1653). Les Landes remained a patchwork of small 'pays', local lands with many being ancient viscountcies, until 1790 when the département of Les Landes was created to become the second largest département of France after Gironde. At first, the département was divided into four districts whose chief towns [chief-lieux] were Mont de Marsan, Dax, Tartas and Saint Sever. Mont de Marsan, Dax and Tartas competed for leadership of the département, with 'certain protagonists' leaning towards dividing the département in two, to separate Dax and Mont de Marsan. In the end, it was Mont de Marsan that became the chief-lieu of Les Landes, its capital and home of the prefecture, while Dax holds the sous-prefecture and the bishopric of Landes.

why fortified churches were built

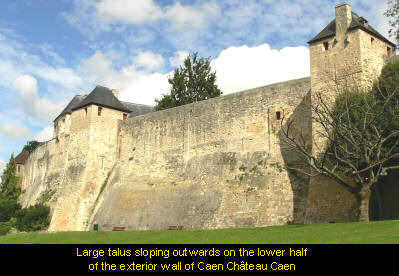

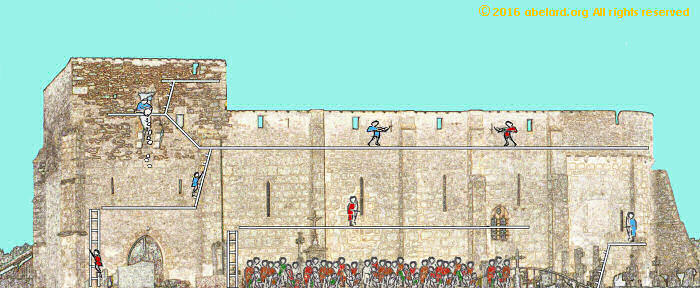

Some, but not all, Landaise churches are fortified at least to some degree. Then there are churches that were once fortified, but have been transformed through 'modernisation', like at Rion-des-Landes which was rebuilt in 1866. Many of the fortified churches have been 'improved' by the addition of a roof to the square, often crenellated tower. Frequently, the roof is further 'modernised' by being made as an Imperial-style roof : a fancy, slate, pointy bath hat, as at Poyartin [left]. There are some churches that are the equivalent of flat-pack constructions, chosen from a catalogue and looking pretty standardised and personality-less, but maybe adorned with a fortified motif or two, like arrow slits, rather like go-faster stripes on cheap cars [right]. abelard.org looks in some detail at fortified churches that exemplify particular characteristics of the fortified church,or other characteristics of note. fortifying a churchSeveral defensive systems were used by the inhabitants to obtain a more efficient resistance of their church.

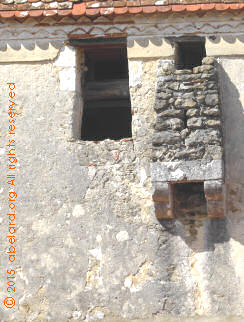

safe roomImitated in in current times, this room of last resort was constructed under the eaves, close to the military walkway on high. Safe rooms are often marked by openings in the church wall close under the roof's eaves. See, for example, Saint-Laurent-en-Parentis. Many of the safe rooms that were on a floor above the main body of a church were destroyed, along with the defenders' fighting platform around the top of the church (and and under the eaves if there was a roof at that time), when churches were 'improved', modernised, with vaulted ceilings in the nave. From Lesgor to Arujanx, many are the churches that have lost almost evidence of safe rooms, except the window openings high up under the eaves.

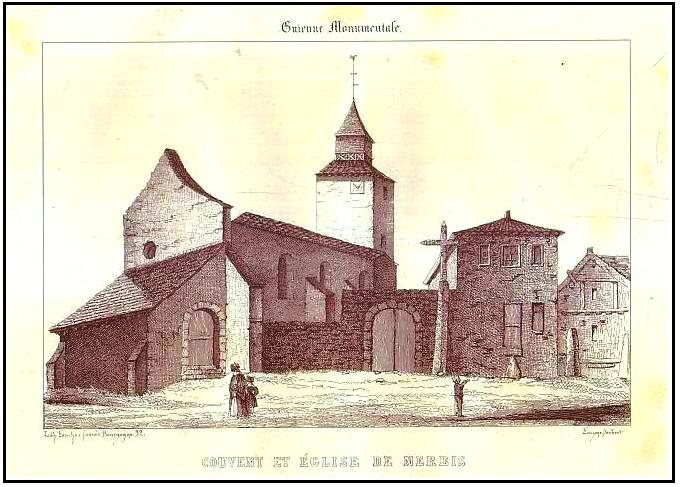

the motteIn the long past, many village churches in Les Landes were built on higher points, including the artificial heights of a major heaping of mud, rocks, and stones called a motte. Examples of churches built on or near the protection of a motte include those at Baigts, Lencouacq, Estibeaux, and Nerbis. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

new! Cathedrale Saint-Gatien at Tours

|

fortified churches in detailOf the 150 or so fortified churches in the département of Les Landes, a proportion clearly exhibit one or more defensive attribute, or are notable in other manners. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The west porch-tower is very massive and flanked by a polygonal stair tower. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

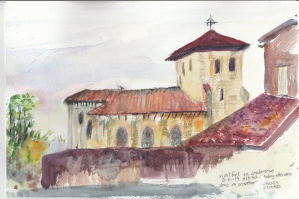

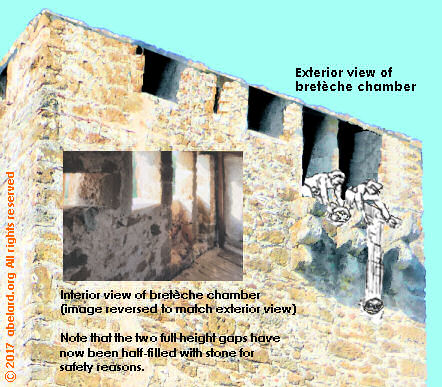

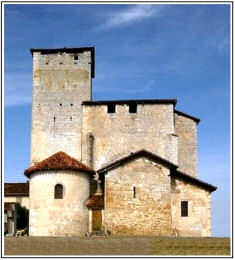

One of the best preserved fortified churches in Les Landes, despite its more recent roof, that includes a belfry on the tower portion. There is a marked line, a change in stone, that divides the first, primitive church, and the later addition. This is particularly visible on the apse (to the east) and the 12-metre tower (to the west). At first this added level would have had no roof, being a open-air defensive platform and walkway. Later, the roof was added to protect defenders from arrows and the weather There is the remains of a large bretèche defending the main door, which can be reached from the defensive platform around the nave. There are also a variety of meurtières below the roof. The wall surrounding the cemetery was once higher, the first defence against attackers. Note also the primitive, flat, full height buttressing that supports the building against outward pressures. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This area was occupied by the Romans, including a camp a bit further north-east from the site of this church. The church itself, constructed between 1075 and 1125, was built on the site of an iron-age necropolis. This very early, small church was built at a high point that surveyed the surrounding country before the widespread planting of pine trees from the mid-nineteenth century. Unusually, the church has two apses. Their rounded ends enable unobscured observation and defence of the surrounding area. The apse at the west end was added later to the donjon tower. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

image: landesenvrac-blogspot-com |

Sarbazan : Constructed with a short nave and flat chevet, the church of Saint-Pierre apparently dates back to the eleventh century. It was probably built, in part, of recycled stone. In the twelfth century, the church was enlarged to the south by a bay on which a semi-circular apsidiole was grafted. It was fortified in the fourteenth century by the addition of a high defensive tower pierced with cross-shaped loopholes. Beside the tower is a safe room. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

During the Gothic period of the 13th century, when the local population expanded, the 12th century apse was pierced by six windows and raised, with enormous buttresses added to support it. A fortified tower was grafted onto the north apse. The defences are completed by a surrounding wall reinforced by towers, built at the end of the16th century, during the Wars of Religion. (To note, in the south facade is a small low opening with an indented lintel, now blocked, that was the lepers' entrance.) Replacing an older, more modest doorway, the main, Flamboyant doorway, built in the 15th century, is decorated by carved pinnacles, vegetative crosses and statues. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Magescq :

A walkway crowns the nave and a crenellated safe room prolongs it to the east on the vault of the Roman choir. The tower, adorned with an imperial-style roof, like at Montfort, is much later. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

the original 12th century church was built on a small hill, a little south and apart from a bastide town. The church was enlarged in the 14th century when the square tower was added to the nave. This church still retains the high wall enclosing both the church and cemetery, a wall which was often been lowered after the wars of religion ended, as at Lesgor. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Built on a mound or motte as a defensive measure. Note the motte has been much domesticated over the centuries.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Previously, the commune of Lencouacq was much more affluent, affording the construction of a wide west front with many architectural motifs, and a large domed squared apse at the east. This is a church built on a motte (an earth mound) so attackers are at disadvantage by having to approach uphill. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Lencouacq church, west facade |

Lencouacq church, apse viewed from the north |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

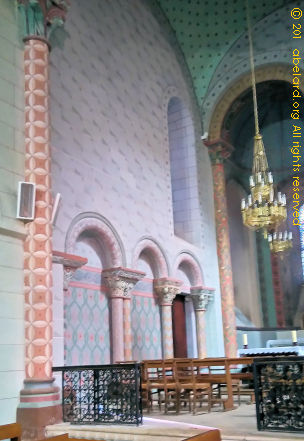

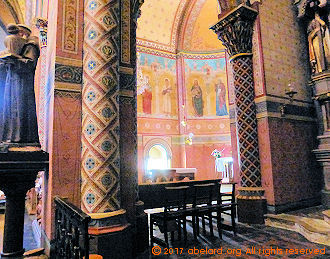

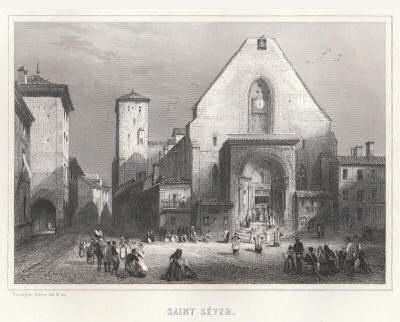

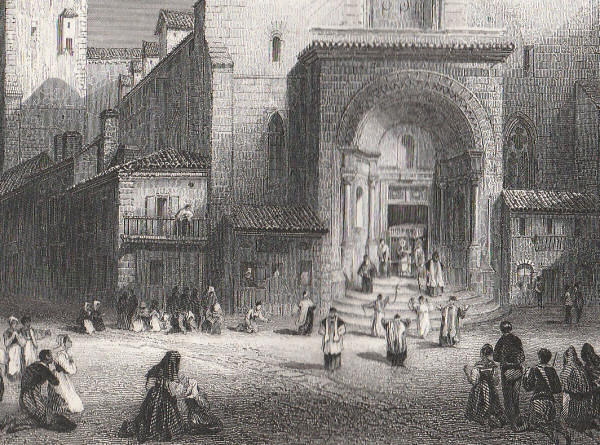

This church is unusual. It started with just a central aisle in the nave, with its apse. To this was added, by the end of the XIth century, the six minor apses, or apselets (absidiole). The presence of seven parallel and stepped (échelonnées) 'apselets' form a very complex chevet (eastern end) in the Benedictine style are witness to a sort of revolution in the concept of the edifice during its construction. To the three classic apses of the initial plan have been appended four others. But the central apse, the highest and widest, was almost entirely rebuilt in the XVIIth century, while several of the minor apses have been reworked, covered in rendering, so there is only one minor apse that still has its original Romanesque coloured decoration. There are 150 capitals on columns, of which 77 are identified as Gallo-Roman and Romanesque. The polychrome capitals decorated with lions date from the eleventh century. The Corinthian capitals have figurative decorations and story-telling capitals. They had the function of teaching Christian culture. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Saint-Sever-sur-Adour Abbey in 2015 |

west facade Saint-Sever-sur-Adour Abbey facade in 1684, engraved by Rouargue in 1845 Note that the breteche on the right side of the tower now no longer exists. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Enlargement of the main happening in the engraving above, which probably shows the presentation of the relics of Saint Sever, evangeliser of Gascony beheaded by the Vandals in the early sixth century. These relics are now kept in the central apse. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

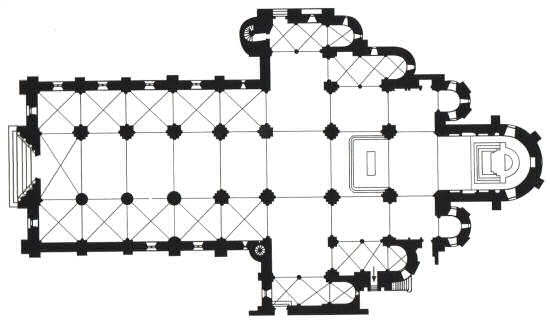

Right: Floor plan of Saint-Sever abbey church

Above: Smiling lions on a column's capital |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

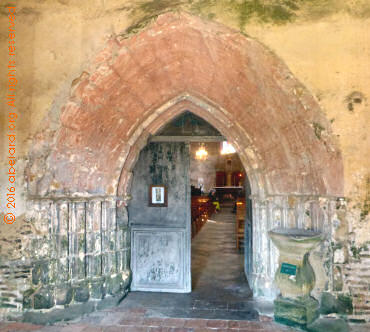

Extensively rebuilt in Gothic style, while conserving the Romanesque, richly decorated, west porch and facade. This town is now less rich than in the heyday of the forestry industries. In the 11th century, a Romanesque church was built. In the 16th century, the church was rebuilt and heavily fortified, apparently "the most beautiful of its type in Landes". The cemetery outside the church had 5-metre high walls, a metre thick and crenellated all round. The church included a quadrangular tower with three floors that defended the entrance door beneath the tower. The walls of the church, over a metre thick, were in dressed stone. The stairs to the room above the nave vault and to the tower walls built en colimaçon - in a circular helix (coming from the Norman word, calimachon, meaning snail). Over the vault was as much floor space as that of the church. In 1864, when the Rionnais had become rich, the church was pretty well destroyed - it was decided to build a new church to accommodate the then rapidly increasing population. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Rion-des-Landes church, from south-west |

![12th century doorway [portail] with six Sarrancolin marble columns.](fortified/rion-des-landes2.jpg) 12th century doorway [portail] with six Sarrancolin marble columns. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

charming, smaller churchesÉglise Saint Vincent, Tarnos : |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Right: The interior of Saint Vincent Church |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Église Saint-Loubouer, Saint-Loubouer

The church of Saint-Loubouer, in the village of the same name, was founded by its namesake, along with a Benedictine monastery next door. All went well until, in the XVIth century, Queen Jeanne d'Albert, Queen of Navarre and holder of great swathes of land in Bearn and Les Landes, converted to Martin Luther's Protestantism, then termed Huguenotism. In her fervour, Jean Albret laid waste to much of Les landes, destroying Catholic churches, killing priests and monks, as well as those slow to convert. Saint-Loubouer was one such church that was almost razed to the ground, leaving just the tower and the end of the apse, the monks fleeing to Saint-Sever. Much of the stone was then taken by locals to rebuild and repair their homes. In due course, when things had quietened, the church was rebuilt using some of the original stones recovered from pilfering locals. Instead of the elegant columns with carved capitals, stones were stacked into stolid square-sectioned pillars. Some of the original carved capitals were added to the top of these new pillars, while the rest now line the exterior wall, made of dressed molasse block

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

on stoneThe reason why churches were so often fortified is that they were built of stone, solid stone. In Les Landes, a department created from millennia of sand drifting inland from the Atlantic ocean, creating a sandy landscape of dunes, marshes, often silting rivers and large ponds, known locally as étangs. Thus stone was and is not easily available in large quantities, while much is sedimentary rock, crumbly and relatively soft. Out in these unspoilt, untamed lands, often floors are tiled with simple patterns of two or three colours.

Many altar pieces have insets of what are imitation marbles painted on wood in two or three colours. These are fairly peasant handcrafts, done in a spirit of simple piety, within the capacity of what has often been a poor, countryside département. During the Mid-Miocene epoch, between 11 and 16 million years ago, the Atlantic Ocean invaded the Aquitanian Basin, including Bas-Armagnac. The sea laid down continental deposits that are now grouped under the general term of “Fawn-coloured Sands”. These continental deposits include molasse - sandstones, shales, or even gravel [see to right] - that were laid down as shore or foreland layers containing fossils of many terrestrial species. Bas-Armagnac soil is composed of clay-silicate layers, covered by ochre sands and a fine clay now used for making ceramics. From these deposits are produced elegant brandies with delicate bouquets, particularly with nuances of prune. galuche (or galoche)There is another rock that was found in some parts of Les Landes - galuche (or galoche), a dark lumpy rock that contains large quantities of iron ore. This gives the rock a dark red hue. Because of the iron content, galuche was often quarried and smelted as part of one of Less Landes' former industries. The stone has now been worked out and the forges are now silent, although some towns still hold a memento of this industrial period in their names : Pontenx-Les-Forges, the Les Forges Restaurant at Castets. Another reminder is the use of this brown-red stone for building. Houses and churches have dark stone included in their walls, and sometimes with churches, they are built entirely in galuche. Now galuche is easily eroded by rain and,in the past, waas commonly known as "the wrong stone". Because this stone is so friable, most frequently galuche buildings are hidden in a drab overcoat of concrete or rendering, known as crepi in French, or a heavy lime plaster (chaume). Fortunately, in one town - Mezos, as part of restoring their heritage, the local worthies had the protective disguise removed to reveal an unusual but magnificent church.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

on decorationBefore the advent of the suppression of manifestations of joy its many forms: Calvinism, Puritanism, Protestantism or, in France, the Hugenuots and the French Revolutionaries - walls were brightly, heavily decorated with coloured designs and patterns, as well as mural pictures. As a quick method of hiding these signs of fun and happiness, many gallons of whitewash were used the turn walls pristine, pure white. This happened widely in churches, as well as, less often, in buildings for living. Now, in the twenty-first century, archeological restorations are finding both fragments and extensive areas of wall decoration. Other churches have been fortunate enough in France not to have been desecrated in this fashion. Below is a small selection from decorated churches in Les Landes.

some examples outside Les LandesBeaumont-du-Périgord (Beaufort) bibliography

end notes

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

email email_abelard [at] abelard.org © abelard, 2017, 5 march the address for this document is https://www.abelard.org/france/fortified-churches-landes.php |

In this poor region with few castle forts, the only refuge in stone was often the church, so the parishioners fortified that according to their means.

In this poor region with few castle forts, the only refuge in stone was often the church, so the parishioners fortified that according to their means.