related pages:

|

- introduction

amiens

- museum

of stone carving

recumbent bronzes

the labyrinth

damage

in world war 1

the

choir stalls of amiens cathedral

the

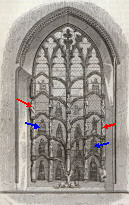

stained glass at amiens

buttressing and chainage

- beauvais

- some

history and interesting facts

world war

2 damage

glass at beauvais

- bibliography

end notes

Just as in the modern age, where

every ambitious builder in New York strove to build an

ever higher skyscraper, a vanity that now has spread around

the world, the cities of France sought to outdo their

rivals with ever bigger and taller cathedrals.

During the great cathedral-building craze, the vaults at Laon rose to 79 feet/24 m, those at Paris managed 110

feet/33.5 m, Chartres 114 feet/34.75 m, then 125 feet/38

m at Reims, then another leap to 135 feet/41.2 m at Amiens,

and finally Beauvais hit the sky at 157 feet 6 inches/48

m - the only trouble was, they never could quite manage

to make it stay up - the winner.

Biggest, longest, tallest, fattest, a lot of the time

it depends on what and how you measure. Outside or inside,

a chapel that has been added or that spire anybody can

build on top, like a flagpole or aerial on a skyscraper.

The Great Pyramid rose to a bit over 145 metres, but has

lost about 10 metres as it has eroded down the ages. |

|

Various European spires ran up above 150 metres while

in France, Rouen topped 150 metres in the 19th century

with a cast iron version was added. The age of iron and

steel frames was upon us, the Eiffel Tower reaching 320

metres in 1889. But between the pyramids and the age of

iron and steel, the cathedrals were the tallest structures

in the world.

While Beauvais built higher, Amiens built bigger. It

is said that Amiens cathedral was able to accommodate

the whole 10,000 population of the medieval town. |

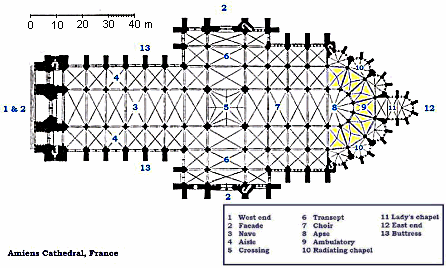

Above: Plan of Amiens cathedral.

The building covers an area of 7,700 m².

Its internal volume is 200,000 m³.

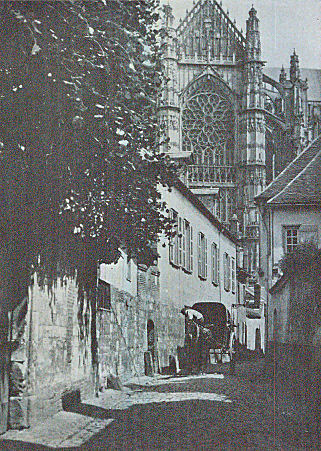

right: Beauvais cathedral looms over the surrounding streets. |

|

|

|

new :

on first arriving

in France - driving

France is not

England

Marianne - a French

national symbol, with French definitive stamps

the calendar

of the French Revolution

the

6th bridge at Rouen: Pont Gustave Flaubert,

new vertical lift bridge

Futuroscope

Vulcania

the French

umbrella & Aurillac

the

forest in Aquitaine, as seen by francois mauriac, and

today

places

and playtime

roundabout

art of Les Landes

50 years

old: Citroën

DS

the Citroën

2CV:

a French

motoring icon

la

belle époque

Pic

du Midi - observing stars clearly, A64

Carcassonne,

A61: world heritage fortified city

Grand Palais,

Paris

mardi gras! carnival

in Basque country

what a hair cut! m

& French pop/rock

country life

in France: the poultry fair

short

biography of Pierre (Peter) Abelard

Grand Palais,

Paris

dating old

postcards

bastide towns

the greatest show

on Earth - the Tour de France

Futuroscope

Vulcania

Space City, Toulouse

|

La cathedrale d'Amiens

The west front of Amiens cathedral is sometimes considered the

most perfect and complete gothic facade. My first impression

on mounting the parvis of Amiens is almost confusion,

with the surfeit of carven stone bodies. I don’t

much like crowds, and west front is like a crowd when

first seen. It is over time that the more interesting

details are gradually comprehended.

Panorama of Amiens (19th century)

museum

of stone carving

the

recumbent bronzes

“Two remarkable monuments of bronze, at the entrance

of the nave from the western porch, were erected in

memory of the founders of the church, Bishops Evrard

and Gaudefroy. Upon the cenotaph of Evrard, the bishop

is represented giving his benediction and trampling

under his feet two dragons; round the tomb is a leonine

inscription in Lombardic characters. The cenotaph of

Bishop Gaudefroy d'Eu, on the opposite side of the entrance,

and of the same material, differs little in its design

and execution from that of Evrard. Both monuments were

formerly placed in the middle of the nave, but were

removed to the present site in 1762. Monuments of bronze

are extremely rare in France, in consequence of the

desecration of the churches of this kingdom during the

eventful revolution of 1789.”

[p. 23, French

cathedrals by Benjamin Winkles, Robert Garland,

1837]

|

|

| Bronze memorial to

Bishop Geoffroy |

Bronze memorial

to Bishop Evrard |

Around the edge of each gisant (recumbent) statue

is a dedication.

That of Bishop Everard de Fouilloy

(died 1222) has engraved this inscription :

“Qui populum pavit, qui fundamêta locavit

Huiûs structure, cuius fuit urbs data cure

Hic redolens nardus famâ, requiescit Ewardus,

Vir pius ahflictos, vidvis tutela, relictis

Custos, quos poterat recreabat munere ; ύbis

Mitib aguus erat, tumidis leo, lima supbis”

|

|

“Who fed the people, who laid

the foundations of this

Structure, to whose care the City was given,

Here, in ever-breathing balm of fame, rests Everard.

A man compassionate to the afflicted, the widow’s

protector, the orphan’s

Guardian. Whom he could, he recreated with gifts.

To words of men,

If gentle, a lamb ; if violent, a lion ; if proud,

biting steel.” [John Ruskin] |

That for Geoffroy d’Eu (died 1237) :

“Ecce premunt humile Gaufridi membra cubile.

Seu minus aut simile nobis parat omnibus ille ;

Quem laurus gemina decoraverat, in medicinâ

Lege qû divina, decuerunt cornua bina ;

Clare vir Augensis, quo sedes Ambianensis

Crevit in imensis ; in cœlis auctus, Amen,

sis.”

[Note this is in rhyming couplets.]

|

|

“Behold, Geoffrey’s limbs

are pressing his humble bed.

Whether less, or like us, he is preparing for all;

Whom the twin laurels adorn, in medicine

And the divine law, the

glory of two horns;

Illustrious man of Eu, whose see is Amiens,

Grew in stature; increased in heaven, Amen, if you

wish.” |

“The labyrinths of Rheims,

Chartres, and Amiens possessed in common a feature

which has given rise to much discussion, namely, a

figure or figures at the centre representing, it is

believed, the architects of the edifices.

Original central medallion of Amiens Labyrinth

“That of Amiens is preserved in Amiens Museum

and consists of an octagonal grey marble slab with

a central cross, between the limbs of which are arranged

figures representing Bishop Evrard and the three architects,

Robert de Luzarches, Thomas de Cormont and his son

Regnault, together with four angels. A long inscription

accompanied it, relating to the foundation of the

Cathedral.” [Quoted from sacred-texts.com]

Reconstruction of the central medallion in the original Amiens labyrinth, now part of the current labyrinth

A : Bishop

Evrard de Fouilloy +1222

B : Architect Maïtre

Robert de Luzarches +1223

C : Architect Maïtre

Thomas de Cormont +1240

D : Architect Maitre Renaut

de Cormont

a : En l'an

de grâce mil II.c

Et XX fu l'œuvre de cheens |

In the year of grace thousand two hundred

And twenty was this work |

b : Premièrement

en comenchie

A dont yert de cheste Evesquie |

First begun

The bishop of this diocese was |

c : EVRART Evesques benis

Et Roy de France Loys. |

Evrard blessed Bishop and the

King of France was Louis [VIII] |

d : Q. fu

filz Phelippe Lesage

Chil. Q. maistre yert de l'œuvre |

Who was son of Philip the Wise

He who was master of the work |

e : Maistre

Robert estoit nomes

Et de Lusarches surnomes. |

Was named Master Robert and

surnamed de Luzarches. |

f : Maistre

Thomas fu après luy

De Cormot. Et après sen filz |

Master Thomas de Cormont was

after him. And afterwards his son |

g : Maistre

Regnault qui master

Fist à chest point Chichester lecture |

Master Renaut who had

placed at this spot |

h : Que

reincarnation valuate

Exilic an mains XII en Fallot. |

This inscription

in the year of incarnation 1288. |

“Evrard de Fouilloy, 45th bishop of

Amiens, placed the first stone of the cathedral of this

town in 1220, under the pontificate of Honour

III. The walls had hardly left the ground when he died.

Gaudefroy of Eu, his successor, raised the walls from

the cobble stones to the vaults. Bishop Arnoult constructed

the vaults, the galleries outside and a bell tower,

all of which no longer exists. At last, this beautiful

edifice was finished in 1288, with the exception of

the towers, which for lack of funds, were not finished

until the 14th century.

“Robert de Lusarches, the most famous architect

of the time, drew the plan of the cathedral and started

construction. After his death, Thomas de Cormont continued

the works and Renault, his son, finished them.

“This is what the following inscription describes,

an inscription on a copper strip at the centre of a

maze of blue and white stones that used to be in the

middle of the nave cobbles.”

[From Histoire

de la ville d'Amiens: depuis les Gaulois jusqu'en 1830 by Hyacinthe Duseve, 1835, vol. 1 pp. 174-6]

The original labyrinth at Amiens was constructed in 1288,

being 12.8 metres (42 feet) in diameter. It was destroyed in 1825. The drawing below appears to have been made before that labyrinth's destruction … or maybe not.

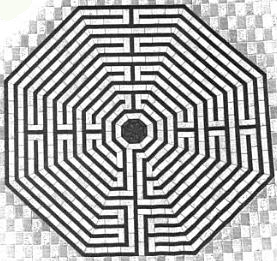

Original? Amiens labyrinth, drawn by Jules Gailhabaud [1810-1888],

in L'architecture

du 5me au 17me siècle et les arts qui en dépendent, Volume

2, 1858

(unpaginated book, about 3/4 of the way through)

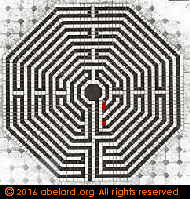

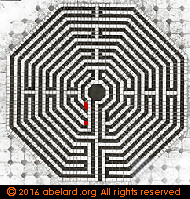

The current labyrinth, restored in 1894, is in the nave between other tiling.

It is 12.1 metres in diameter. The design can be difficult to follow as chairs, billboards and

other church clutter tend to be put there willy-nilly. The labyrinth is made from black marble and Basz yellow-white tiles from Lunel. It is known here as the "House of Dedale".

Amiens labyrinth. Image: Maurice Duvanel

However, if you take the drawing by Gailhabaud (a bit above), and reverse it black to white and white to black (similarly to making a negative), and then flip that reversed image left to right, magically it becomes the pattern for the present Amiens labyrinth. However, as you can see, the actual Amiens labyrinth has a redundant and confusing black line surrounding it. |

| the labyrinth at Amiens cathedral |

|

|

|

|

|

| drawing by Gailhabaud, attributed by him to Amiens labyrinth |

made into a negative image |

flipped on the vertical axis |

|

photo of the actual labyrinth at Amiens |

The story then becomes stranger still. Gailhabaud shows the illustration, left below, for the labyrinth at Saint Quentin. This labyrinth illustration, in fact, corresponds to the actual labyrinth at Amiens (far right in the series above). It does not correspond to the actual labyrinth at Saint Quentin. To obtain the actual labyrinth at Saint Quentin, the Gailhabaud drawing must be flipped from left to right!

| the labyrinth at the basilica of Saint Quentin |

|

|

|

Saint Quentin labyrinth, drawn by Gailhabaud

Note: the drawing has an error, missing two bars. abelard.org has added these bars in red.] |

flipped on the vertical axis |

photo of the actual labyrinth

at Saint Quentin |

|

| |

Damage

in World War 1

Amiens was near to, though not at, the First World War

front line. On 31 August 1914, forward units of the German

army entered Amiens, and immediately started their habitual

looting and bullying. During this, the Germans also kidnapped

about a thousand young men, sending them into captivity.

About a week later, they were forced to turn tail as

the main German offensive was blocked. They finally left

on 17 September (the defeat on the Marne).

On 21 March 1918, Ludendorff opened a great offensive

with a million troops, in order to break out. He was steadily

ground down and stopped, being unable to enter Amiens

but, of course, this did not stop the Germans from regularly

shelling the town. During this time, the cathedral was

hit nine times.

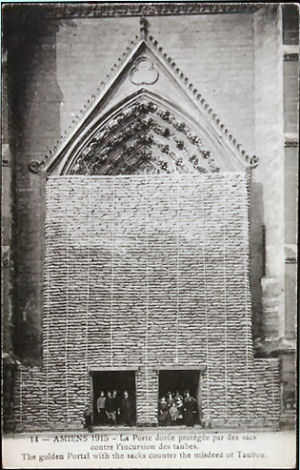

Without the Germans in the town, the people of Amiens

were able to heavily protect the cathedral inside and

out, and to remove the stained glass and other treasures

to safety. So while some damage was done to the cathedral,

it was minimised.

above: southern transept door,

the door of the golden Virgin, protected by sandbags,

1915 |

above:

the choir stalls protected by sandbagging. above:

the choir stalls protected by sandbagging.

below: effects of the first

shells which hit the cathedral (aspect: inside the

nave)

|

|

above: chapel of St. John the

Baptist damaged by a shell (left-hand side of apse)

|

related material:

Germans

in France

the

choir stalls of Amiens cathedral

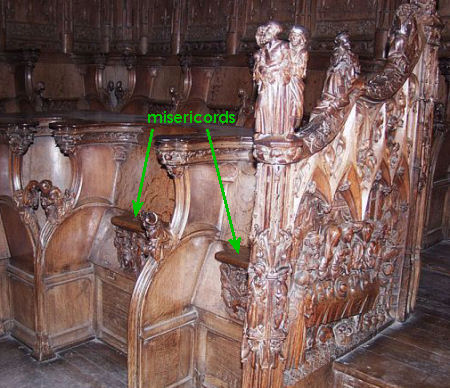

The

choir (chœur in French) is where the clerics

attached to the cathedral’s chapter (or religious

hierarchy) gathered during prayers and services. The

choir (chœur in French) is where the clerics

attached to the cathedral’s chapter (or religious

hierarchy) gathered during prayers and services.

The clerics were not allowed to sit in “the presence

of the Lord” and the ceremonies could continue for

hours on end. The priests and monks were allowed a concession

of a little ledge on which to rest their bottom while

appearing to be standing. These ledges are called misericords

(also spelt misericorde, misercord = mercy), and were justified by being the location

for fancy carving on religious topics or stories from

the bible.

The choir stalls at Amiens are considered to be among

the best anywhere. They certainly are splendid, but I

prefer the

choir stalls at Auch. They are an extraordinary treasure

hidden at the heart of that cathedral, with primitive

naive energy, both in the subjects and in their implementation.

Two choir stalls at Amiens cathedral

with their misericords marked.

Misercord showing baby Moses being

found in a basket by the river Nile.

Feast of Cana carving on the side

of a choir stall.

The Amiens choir stalls were made between 1495-1530.

The artists were Arnould Boulin, Alexandre Huet and Jean

Trupin. More images of the stalls are available at princeton.edu. This

is the introductory page to Amiens. Many more choir stalls

can be viewed via drop-downs on this page.

|

Dating from the end of the 13th century

What a strong chin!

|

the stained

glass at amiens

Amiens

cathedral has a stained glass collection of shreds and

shards ranging over several centuries and several styles. Amiens

cathedral has a stained glass collection of shreds and

shards ranging over several centuries and several styles.

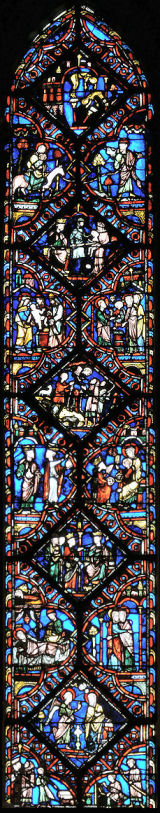

The earliest glass, dating from the 1230s, showed the

various artistic fashions in the 13th century. This early

glass was the lowest glass in the nave; finished in 1236,

but destroyed at the end of the 13th century when the

side chapels were built. The few vestiges were scattered

in various depots and museums. The majority of this glass

was gathered together, organised and conserved in 1830

by the painter and glazier, M.-H. Touzet. The pieces were

placed in Bay 27 on the north side. There, they have been

reunited in a forced fashion in three lancets, with story

compartments, mostly from Genesis, arranged around a central

ornamental motif.

During the Middle Ages, the wealth of Amiens was based

on guède production and dying, becoming

the main centre in France. Guède was the

French name for woad, a blue dye originating from Isatis

tinctoria leaves. More recently, in France, it is

usually called pastel. The dye is used for clothing (French

Army uniforms and American denim jeans for instance) and

paints, among other things. Several Amiens worthies, who

had created their wealth through guède manufacture and trade, made donations towards the construction

of Amiens cathedral.

One of these donors, Andrieu Malherbe donated the glass

shown here to the right in 1296 [located in Bay 39]. Malherbe

was a rich burger of Amiens. He became mayor [maieur, mayeur] of Amiensin 1292, and died in 1293. His

first name was sometimes written as André, and

was also shortened to Drieu or Dreux. His wife was called

Maroie. His coat of arms carried a fleur-de-lys (semé

de France) on a ground of argent, with four azur

tortoises.

Drieu Malherbe had acquired in 1291, from the chamberlain

of King Philippe-le-Bel [1285 - 1314, father of Henry

IV of Navarre] for about 1,000 pounds, the right of tonlieu for guaide [guède] in Amiens.

In feudal law, the right to tonlieu is a tax

levied for the display of merchandise in the markets.

It is also a toll levied on goods transported across of

a river by bridge or by ferry, or through the gates of

the city.

Thus Malherbe could collect tolls and levees on the guède traffic and its revenues. These

amounted to about 550 pounds a year. Dreux Malherbe, who

died in 1295, left in his will to the town of Amiens,

this right to collect taxes on guède,

which produced a not inconsiderable income and was to

be distributed as alms and be used to found two chapels,

one in the church of Notre-Dame d'Amiens, the other in

the church of Saint-Nicolas and the Poor Clerks.

Amiens account registers show that the town paid annually

from the alms of Lord Drieu Malherbe:

To Saint-Ladre annually, on the day of Mid-Lent - 30

pounds

To the hospital in front of Saint-Leu, on Saint Jean-Baptiste’s

Day - 20 pounds

To the God of Amiens hostel, on the day of Mid-Lent

- 60 pounds

To the convent of minor brothers, the same day - 60

pounds

To the convent of preacher brothers, the same day -

30 pounds

To the chaplain of the chapel of the Poor-clerks, on

saint Christopher’s day - 30 pounds

To the chaplain of the Saint Agnes chapel in the Notre-Dame

church, on Saint Jean-Baptiste’s Day - 30 pounds

To the Mayor of Amiens as alms which he gave in great

blankets and shoes to the poor on Toussaint [1st November]

and the Day of Souls [2nd November] - 11 pounds

Derived from Le

Livre d'or de la municipalité amiénoise [The book of gold of the Amiens municipality], GoogleBook

pp. 40 - 41

and Le

premier livre des Antiquitez, Histoires et Choses plus

remarquables de la ville d'Amiens, poëtiquement

traité [The first book of Antiquities,

History and Things most remarkable of Amiens, poetically

treated] by Adrian de La Morlière, 1626 - p.318

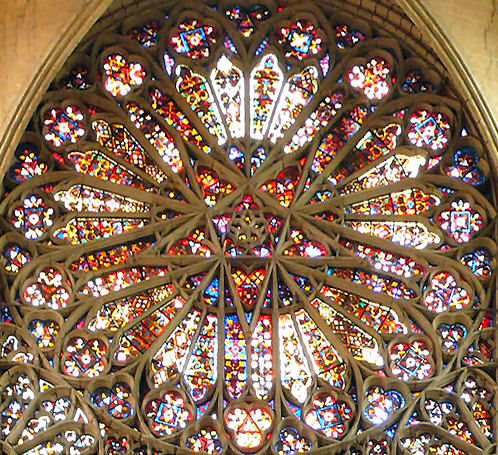

Two panels from the south rose window,

end of 15th to start of 16th century

The transparency of the North transept rose,

with pentagon and pentagram centre

Common among Victorians was the fancy that the rose windows of a cathedral like Amiens somehow incorporated magical reference to the four ancient elements of earth, fire, air, and water - a bit strained when you have to cram the four elements into three rose windows. To skid around this inconvenience, the west window was deemed to incorporate both earth and air. The north window was more easily associated with the transparency of water, while the south window could be associated with the darker reds and oranges of fire.

The standard colours of the four elements were attributed as earth>green; air>yellow or perhaps grey, white, or blue; fire>red or orange; and water>blue. As you can see, there is a bit of a struggle with the colours of air, though the others are fairly conventional.

|

|

|

| Amiens cathedral west rose |

Amiens cathedral north rose |

Amiens cathedral south rose |

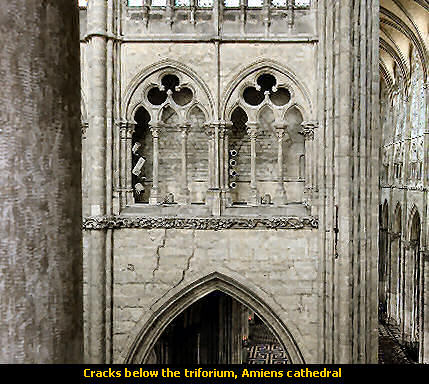

buttressing and chainage

To help protect the cathedral from literally falling apart from the strains generated by building such a large structure that led to it being rather unstable, chains of iron stabilising rods [chaînage, chainage] were added, generally hidden galleries and passages.

The building of Amiens cathedral, a huge cathedral only capped in height by Beauvais, was much effected by the then nascent knowledge of structural engineering, and by the ambitions of the builders and the people who commission the construction. The flying buttresses were not always sufficient, or were not placed to apply a counter pressure in the right position to prevent the stone shifting so cracks appear, columns to bow and arches threaten to collapse.

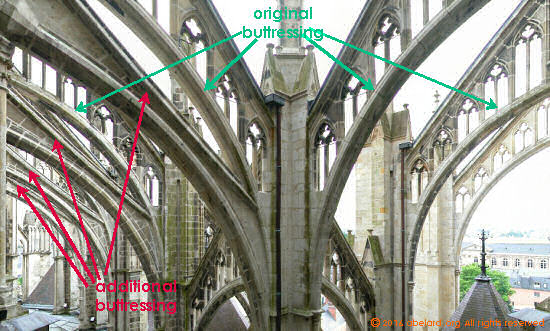

To correct the problems that appeared, the builders at Amiens took two main steps. One was adding better positioned buttressing. The original flying buttresses had been placed so their point of reinforcement was too high, and so not effective. Additional buttressing was added later to correct the problem.

Above and right: Double buttressing at Amiens

|

|

|

| |

The original buttressing to the south-east crossing of the transept and nave are among the most beautiful of any cathedral, and were designed to support both the clerestory wall and the high vaults. Unfortunately, the artistry outran the technology. The lower part of the buttress (marked in green) was placed slightly too high to give sufficient support to the vaults, necessitating an added lower reinforcing buttress (marked in red) in some places. The extra buttress somewhat spoiled the original artistic effect.

The second method for correcting the cathedral's structural problems was giving the cathedral a girdle, at first in wood. This was later replaced with an iron armature, probably forged at the Abbey of Fontenay.

| Background

facts |

Amiens |

- approximate population : 133 354

average altitude/elevation : 33 m

-

Amiens is 87 miles/139 km north of Paris

-

- cathedral dimensions

- external length : 145 m

internal length : 133.5 m

transept external length : 72 m

transept internal length : 62 m

transept width : 29.3 m

nave width : 12.15 m

nave height (under the vaults) : 42.3 m

tower height, to top of spire : 112.7 m

labyrinth (labyrinthe) diameter : 12.1 m

|

|

| |

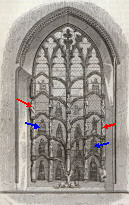

Jesse tree window at Beauvais Jesse tree window at Beauvais |

Beauvais

- The cathedral of St Peter Beauvais

- The cathedral of St Peter

It is a while since I visited Beauvais, and what was

seen has become somewhat impressionistic. Beauvais cathedral

rises like some volcano or primitive dinosaur that has

burst forth from the earth among the houses of the town.

The dominant response I have is ‘scary’,

and that’s just from the outside. The outside isn’t

interesting or very remarkable beyond its great explosion.

But go inside, and until recently, you stepped into a

threatening cauldron, shorn up by an array of iron and

wood. This is the real monster of gothic cathedrals, the

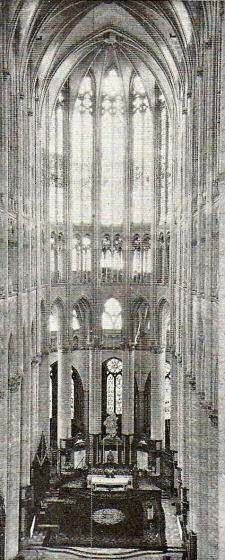

choir vault rising to over 46 metres, that’s over

150 feet. This extraordinary elevation is further emphasised

by the fact that the nave is so short, having never been

completed. There’s no long nave to balance the rocketing

height.

The cathedral may have survived the WW2 incendiary bombardments

that razed much of Beauvais, but this frail stone house

of cards is still at the mercy of man and nature. Gale

force winds originating from the English Channel oscillate

the buttresses and shift the weak roof structure, while

sometimes ill-conceived repairs and restorations to the

structure. Running from the 1950s to the 1980s, one experiment

involved removing many important iron ties from the choir

buttresses. This damaging project was thought to have

been corrected by temporary ties-and-braces in the 1990s.

However, this may have made the building too stiff, so

increasing stresses rather than diminishing them.

But since 2010, this has changed after major consolidation

works were effected, stabilising the heights of the nave.

This stabilisation is even leading to the notion that

perhaps the tower and spire could be re-erected, this

time successfully.

some

history and interesting facts

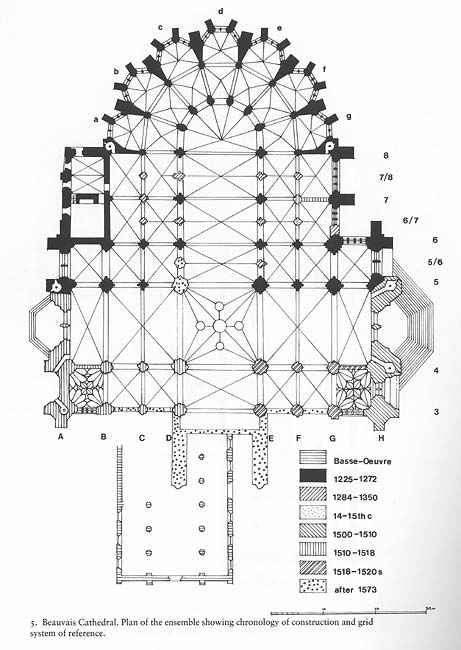

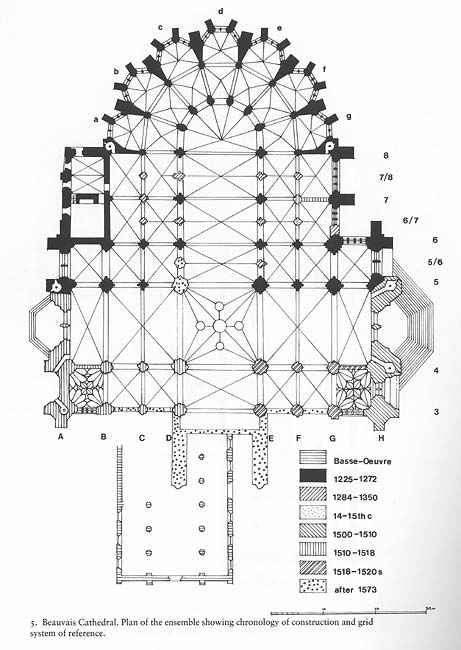

The cathedral, with its five-aisled choir abutted by

a towered transept, was commissioned by Bishop Milon de

Nanteuil in 1225. It was opened in 1272.

The vaulting fell in 1284.

The tower/spire was completed in 1569.

- Four little turrets were supported by the four pillars

of the transept crossing.

- The turrets rose from the roof and met a square,

open tower forty-eight feet high [14.6

m].

- A second tower, octagonal, lace-like, and sixty-three

feet high [19 m],

- The second tower supported a third stage, over forty-nine

feet high [15 m], which was still more lightly

traceried.

- These three divisions more than a hundred

and sixty feet high [49 m] were made of stone,

- and on them rested the ninety-seven foot high [30 m] wooden needle.

- The entire spire rose two hundred and fifty-seven

feet [78 m] above the roofs of the Cathedral

and nearly five hundred feet [152 m] above the ground.

“This new pyramidal spire became the wonder

of the country. "It ... was ... higher than the

famous spire of Strasbourg, and it is said that from

its summit, the houses of Paris were visible."

”

[Cathedrals and cloisters of the Isle de France vol. 2 by Elise Whitlock Rose, pp.293-4]

The tower fell in 1573.

“On the eve of Ascension Day, 1573, a few small

stones began to fall from its heights. The next morning,

a mason, who had been sent to test it, cried out in

alarm; the bearers of the reliquaries, about to join

the Procession of the people and the clergy who were

waiting outside, fled;—there was a violent cracking,—and

in an instant, the vault crashed amidst a storm of dust

and wind. Then, before the eyes of the terrified worshippers,

the triple stories of the lantern sank [like the Twin

Towers on 9-11-2001], the needle fell, and a shower

of stones rained into the church and on the roofs.”

[Cathedrals and cloisters of the Isle de France vol. 2 by Elise Whitlock Rose, pp.296-7]

There is no record of what became of the mason!

It’s almost a shame to go into details rather than

just let the cathedral overwhelm your senses, a bit like

discussing the size of the wheels on a roller coaster.

If the medieval mind ever wished to put you in awe whilst

adding a touch of real-world danger, this is it.

The ominous reason that Beauvais was never completed

is that the original enthusiasts just could not be quite

sure of making it stay up!

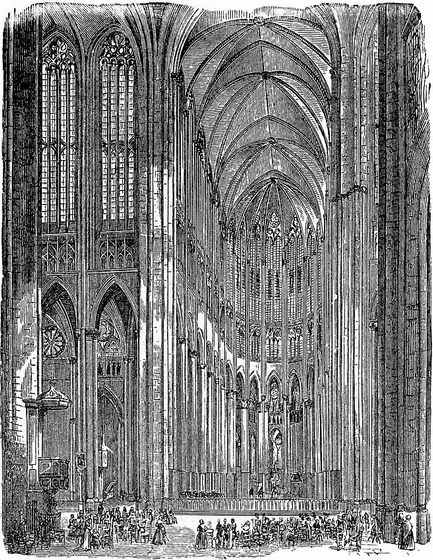

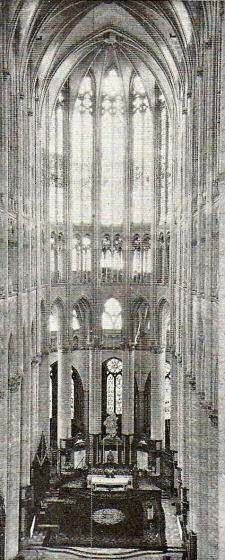

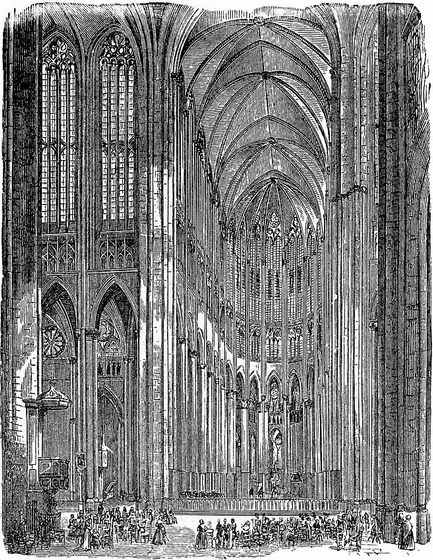

The interior of Beauvais cathedral,

from Grundriss der Kunstgeschichte,

1864

Note the tiny people at the base of the soaring columns |

|

Notice the unusual four levels of windows in this towering cathedral |

All the parts in this vast edifice are derived from

the equilateral triangle, from the floor plan to the

both the overall design and the details of the cross-sections

and elevations. Unfortunately, the cathedral of Beauvais

was erected with too limited resources and weak materials,

as well being provided with a too narrow site. The various

messes, stemming from bad work by unskilled workmen,

necessitated repair and consolidation work, as well

as the doubling of the piers. This last destroyed in

great part the truly prodigious impression made by the

immense nave, so well conceived theoretically and drawn

by a man of genius.

It was the custom and sometimes, as in this instance,

the tragedy of those days, for builders to use the stone

of the region or of some donated quarry, irrespective—and

sometimes in spite—of its quality. This was part

of Beauvais's tragedy. If Beauvais had not been commenced

at a time when the religious and political movement

which had built the Northern Cathedrals had begun to

lose impetus, Saint Peter’s cathedral would have

stood. If the architect had possessed the quarries of

Burgundy, the materials used at Dijon and at Semur,

or the beautiful calcareous stone of Chatillon-sur-Seine,

or even that of Montbard, Austrude, or of Dornecy, or

even—which might have been possible—that

of Laversine, of Crouy, and certain hard strata of the

valleys of the Oise or the Aisne, the work would have

stood. [including abstractions from Viollet Le-Duc vol. VII,

p.549]

Beauvais:

World War 2 damage

Beauvais after German bombing in 1940. The cathedral is

in the foreground.

Early in June 1940, there was several days of heavy bombing.

The Luftwaffe set most of the medieval town alight. Many

were killed, while the tapestry industry was devastated

and a 42,000 book library burnt out.

"In Beauvais, a number of the metallic tie-rods supporting the flying buttresses bear graffiti from the eighteenth century, potentially indicating that the metal may have been a later addition. However certain pieces proved to date back to the beginning of the construction process (around 1225-1240 AD), suggesting that in order to succeed in erecting the world's highest Gothic choir (46.3 meters), iron was combined with stone from the initial design phase."

The Germans smashed Beauvais cathedral in 1940, as can be seen in this image. The upper flying buttresses were destroyed (see right). The Germans smashed Beauvais cathedral in 1940, as can be seen in this image. The upper flying buttresses were destroyed (see right).

Therefore, I am unsure quite what is being claimed here. Maybe some of the bars had been recovered from the rubble.

related material:

Germans

in France |

above and below:

thirteen century glass at Beauvais cathedral

|

A great gothic cathedral is akin to a house of cards.

The great west front and the marching bays of the nave

form a bulwark against the weight of the crossing and,

likewise, the apse at the eastern end. Beauvais in its

incomplete state is unusual, it has no great west front,

no west doors or portals. This is part of why the stability

of Beauvais is somewhat dubious.

glass at

Beauvais

Fortunately, most of the important glass at Beauvais

was removed to safety before the devastation

caused by National Socialism’s Luftwaffe.

The great doors of Beauvais are north and south. Like

much of the cathedral, the transepts containing these

doors date from the sixteenth century and the two great

roses are, therefore, flamboyant.

The north rose is sometimes described as a sun, and rises

above a series of lancets showing sibyls. The south front

has two rows of lancets probably representing kings and

prophets, and is surmounted by a rose that divides into

stories from the Old Testament. It has God at the centre,

surrounded by the seven days of creation and then outside

that, Adam, Noah, Babel, Abraham and Isaac, Joseph, Moses

and the flight from Egypt. At present, I can find no good

illustrations for these roses among my photographs, nor

on the web.

There is generally more academic interest in the medieval

glass, from the 13th, 14th and even 15th centuries. For

example, there are six very nice thirteenth-century lancets

in the apsidal chapel. Their draftsmanship is unusually

good. Pictures of two can be seen at the head

of the Beauvais section, and a couple more next to

this section.

A brilliant book on the early Beauvais glass is Picturing the celestial city by Michael Cothren. This book is expensive, but unlike

most coffee table books, the text is good, coherent and

interesting from beginning to end. It is copiously and

appropriately illustrated. I can recommend this book unreservedly.

Your public library should have a copy, even if you decide

it is too expensive. (This book also does not cover the

later glass.)

I can also recommend Painton Cowen’s brilliant

and growing catalogue

of stained glass windows for those wishing to have

an idea of the glass in the great churches - this

is the link to the Beauvais section. There are links

to other parts of the site available to the left side

of the page. (For Painton

Cowen’s book.)

| Background

facts |

Beauvais |

- approximate population : 53,400

average altitude/elevation : 65 m / 213 ft

Beauvais is 53 miles/84 km north of Paris

-

- cathedral dimensions

- total length : 70 m / 230 ft

tower height : 151.59 m / 497.3 ft

choir vault height : 46.77 m / 153.4 ft

great arcade height : 21.2 m / 69.6 ft

great bay height: 17 m / 56ft

triforium height : 4 m / 13 ft

nave width : 16 m / 52 ft

transept length : 58 m / 190 ft

diameter north rose : 11 m / 36

diameter south rose : 11 m / 36 ft

|

bibliography

Picturing

the celestial city by Michael W. Cothren

|

|

Princeton University

Press, hbk, 2006

ISBN-10: 0691120803

ISBN-13: 978-0691120805

$79.86 [amazon.com]

£66.45 [amazon.co.uk] {advert}

|

|

The Early Iconography of the Tree of Jesse

by A Watson |

|

Oxford University Press

1934, hbk

4to., pp.xiv,197,(xl), navy cloth, gilt, b/w frontispiece, 40 b/w plates to rear of volume |

|

|

In Living Memory: Portraits of the Fourteenth-Century Canons of Dorchester Abbey

by Lucy Freeman Sandler

Nottingham Medieval Studies - 56():pp. 327-349 [22 pages]

BrepolsOnline, Brepols Publishers NV

This publication is sold as a .pdf download of a journal article.

An individual can have "unlimited access" for $22.00 plus tax ($1.21), a total of $23.21.

"To gain access to your content, please go to: www.brepolsonline.net, log on to your account and navigate to your purchased content. If you have questions regarding this purchase, or require additional help, please contact us at Brepols Publishers NV" |

end notes

- The Bible of Amiens by John Ruskin, 1884, chapter 4, p.378.

The

Bible of Amiens is available on the web as

part of a collection. There, it extends from p.273 to

p.412. It is also available on paper in reprints (make

sure you are buying the full version with four chapters)

and secondhand copies.

Chapter 4, starting on p.362 of the online version,

contains a minute description of the statuary of Amiens

cathedral, complete with symbolic meanings.

John Ruskin (1819-1900) spent several years in Amiens,

referring to Amiens cathedral as the “Parthenon

of France”.

The great cathedrals are often referred to as ‘bibles

in stone’, and here you can see Ruskin’s

analysis of the Amiens statuary in that spirit.

- On the inscription, 1288 is written

“Xiij.c ans moins XII”, or “13

hundred years less 12”.

Note that on the copper plaque from the cathedral, the

Roman numerals are written in the normal way as XIII.

The transcription in John Ruskin’s book writes

Roman numerals as was commonly done since medieval times,

with the final ‘i’ of a number group being

written as a ‘j’as a terminator. On medical

prescriptions, the terminating ‘j’ helps

avoid prescribing errors.

Thus, the first ten Roman numerals would be written

j, ij, iij, iv, v, vj, vij, viij, ix, x.

- Tree of Jesse

- A visual representation of the genealogy, the family

tree, of Jesus. The name ‘Jesse Tree’

comes from the Book of Isaiah 11:1, where Jesus is

described as a shoot coming up from the stump of Jesse,

the father of David.

In stained glass depictions, the tree comes from the

side, or the navel, of Jesse lying on a bed. The lineage

shown includes the following list, but may be longer,

including other ancestors such as Solomon.

The characters in the list below of a typical Jesse

tree are accompanied by symbols, which may decorate

the Jesse tree. Bible sources are also included.

Adam and Eve, symbol : apple

(Genesis 2:4-3:24)

Noah : ark or rainbow (Genesis

6:11-22, 7:17-8:12, 20-9:17)

Abraham : knife (Genesis

12:1-7, 15:1-6)

Isaac : ram (Genesis 22:1-19)

Jacob : ladder (Genesis

27:41-28:22)

Joseph : colourful coat (Genesis

37, 39:1-50:21)

Moses : tablets of the law

(Exodus 2:1-4:20)

David : harp (1 Samuel 16:17-23)

Isaiah : lion and lamb (Isaiah

1:10-20, 6:1-13, 8:11-9:7)

Mary : lily (Luke 1:26-38)

Elizabeth : small home (Luke

1:39-55)

Joseph : hammer or saw (Matthew

1:18-25)

- Grundriss

der Kunstgeschichte, 1864, by Wilhelm Lübke

(1826-1893), p.388, fig.227.

-

The hedgehog, elsewhere, is described as an urchin, the bird as a cormorant, a heron, a pelican, or even an owl. Such are the problems in translating from two or three thousand years ago. For a wide-ranging list of translations, see Zephaniah 2-14, and let this be a lesson to you.

[The hedgehog quatrefoil is located at the bottom right of the Saint Fermin door, the north portal of the Great West door.]

- It is traditional to name the doors by the person whose statue is on the trumeau. The south portal is Our Lady. The central portal of the west front is God, who has a small statue of Saint Peter under his feet.

|

Jesse tree window at Beauvais

Jesse tree window at Beauvais

"In Beauvais, a number of the metallic tie-rods supporting the flying buttresses bear graffiti from the eighteenth century, potentially indicating that the metal may have been a later addition. However certain pieces proved to date back to the beginning of the construction process (around 1225-1240 AD), suggesting that in order to succeed in erecting the world's highest Gothic choir (46.3 meters), iron was combined with stone from the initial design phase."

The Germans smashed Beauvais cathedral in 1940, as can be seen in this image. The upper flying buttresses were destroyed (see right).

The Germans smashed Beauvais cathedral in 1940, as can be seen in this image. The upper flying buttresses were destroyed (see right).

![]()