|

|

|

|

||

|

|

cathedral labyrinths and mazes in France

cathedral labyrinths and mazes in France |

|

|||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

introduction

I took very little notice of it then, but recently I have done some investigations to fill the gap of this side-alley of cathedral art. The great, ancient labyrinths are almost all concentrated in northern France. There are many, more recent copies and attempts around the world. For example, a fairly modern attempt can be seen just inside the West Tower of Ely cathedral in England, dating from about 1870. And now a thousand tourist traps attempt to draw in the pennies, they offer patterns for fractious young children to play upon, or maze booklets to colour in or to trace. The Church of Rome has long fought superstition and magical thinking. I prefer to think these patterns were made for contemplation of life's journey, or quiet mediation, or even for dancing energetic and joyous children, while adding interest and designs to the cathedral. Often, as you will see, this is complemented by a bit of historical commemoration and a fascination with mathematical patterns. However, many labyrinths in cathedrals and churches were stripped out during the times of Jansenists and other Puritan sects, as a means of stopping fun so the congregation would concentrate solely on religion. I will not repeat all the dull speculation and magical cant, which you can find across a hundred web sites. Labyrinth or maze?

cathedral plans of labyrinths

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

Plans de labyrinthesFigurés sur le sol des églises cathédrales et autres |

Labyrinth PlansRepresented on the floors of cathedrals and other churches |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| À l'étude du pavage des églises, se rattache tout naturellement celle de son décor, et, par suite, une question interessante qu'enveloppe un certain mystère, mais dont l'origine ou la donnée générale semble remonter aux anciens. Je veux parler d'un de ces usages que le christianisme trouva chez ses prédécesseurs, et dont il toléra la continuité a travers les ages, n'admettant toutefois, de l'idée première, que ce qui pouvait s'adapter au culte, et laissant la portee du symbole paien à l'antiquité, qui, d'abord, l'avait introduit comme ornement du sol. |

The study of the paving of churches, which quite naturally connects with that of church decoration, poses an interesting question, surrounded in a certain mystery about the origin of labyrinths, that origin seeming to date from the ancients. I want to talk of one of those uses that Christianity found amongst its forefathers, that was continued across the ages. Although it may be that, in antiquity, the heathen symbol may have been used for worship, labyrinths were first introduced as ornaments on the ground. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pour traiter cette question aussi complétement que possible, il faudrait avoir produit certains exemples dont j'ai dû reporter la publication au supplément de ce livre. Aussi, constraint par leur absence de remettre notre étude à une époque ultérieure, on comprend que nous n'approfondissions ici aucun des nombreuses points qui la composent, puisqu'on ne saurait les appuyer de preuves. Dans cette conjoncture et en attendant qu'il nous soit donné de l'entreprendre, nous nous renfermerons dans des généralités. Cependant, il convient de déclarer que nous n'envisagerons pas la question du même point de vue que nos devanciers, répétant, sous d'autres formes, des idées déjà emises. Ceux-la n'ont point étudié ou approfondi la matière, qui n'ont su en tirer des aperçus nouveaux, et leurs élucubrations, malgré la peine qu'ils se donnent, ne sauraient faire avancer la science, qu'ils laissent, on doit le dire, toujours au même point. |

To deal with this question [of the origin and purpose of labyrinths] as completely as possible, I should have produced some examples, but doing so would have meant postponing the publication of this supplement to this book. Thus, constrained by their absence to deliver that study at a later time, it is understandable that here we do not study in depth any of its many points, because we do not have supporting evidence. Against this backdrop and until we can undertake the further study, we shall restrict ourselves to generalities. However, it is appropriate to state that we will not consider the question from the same point of view as our predecessors, thus repeating, in other forms, ideas already expressed. That lot definitely have not studied or extended the matter, nor have they been able draw new insights; and with their rantings, despite the energy with which they're given, they could not advance science, which they leave, one must say, always at the same point as before. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| La presente notice est donc plus spécialement consacrée à des considérations générales. D'abord, j'appellerai l'attention sur les formes qui ont été données a ces représentations de prétendus plans de labyrinthes, et je dirai, ensuite, quelques mots du lieu où ils se trouvent. Mais, à ces seuls points ne se borne pas la question; il en est d'autres non moins remplis d'intérêt, et ce sont malheureusement ceux que l'absence des planches nous force de taire. |

Thus, this note is particularly devoted to general considerations. First, I will call attention to the forms given to these representations of alleged plans of labyrinths, and then I will say a few words on the place where they are found. But these points alone do not limit the question; there are others no less full of interest, but unfortunately lacking illustrations, we are forced to make no comment. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| — Sous le rapport des formes, trois surtout semblent avoir été adoptées par les architectes pour la figuration, plus ou moins symbolique, de cette composition ; mais, on doit l'avouer, ces trois formes étaient presque les seules que l'on pût choisir et qui se prètassent aux combinaisons de ce genre : ce furent le rectangle, le polygone et le cercle. Les plus anciennes représentations de plans de labyrinthes sont établies sur les figures de l'ellipse et de rectangle, et ce ne fut qu'un peu tard qu'apparut l'emploi du polygone. Au point de vue graphique, cette dernière figure n'est autre qu'un carré dont l'abattement des angles a donné une forme intermédiaire entre celui-ci et le cercle auquel il mène tout naturellment. |

— Regarding the forms of laybrinths, above all three shapes, more or less symbolic, appear to have been adopted by architects. However, one must admit that these three forms were almost the only ones that could be choosen and they give an air of seriousness to the combinations of this type: these were rectangle, polygon and circle. The oldest representations of labyrinth plans were made in the figures of the ellipse and rectangle, and it was only a little later there appeared the use of the polygon. In graphic terms, this last figure is none other than a square whose corners have been reduced to give an intermediate form between this and the circle to which it naturally leads. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| — Ce premier point établi, restait à varier ou à savoir varier les combinaisons du parcours, et, là, était, pour des artistes, le véritable travail ; mais, s'il faut déterminer ce point d'après les seuls plans qui nous restent, le résultat diminue quelque peu leur mérite ; car, on voit les mêmes dispositions reproduites en divers lieux d'un même pays, mais avec cette modification cependant, soit pour tromper l'œil, soit pour obtenir des variétés, qu'elles sont tantôt en pierres de couleur foncée, en tantôt en pierres de sont clair; j'ajoute même que j'ai constaté des ressemblances identiques entre les compositions de la France et de l'Allemagne, et cette constatation nous prouve que les artistes, parfois, ne faisaient guères de grands frais d'imagination. Sur ce point, doit-on admettre qu'il y eut seulement identité de pensée, ou bien convient-il mieux d'y voir franchement des copies résultant de modèles ou de patrons que toutes les campagnies de logeurs du bon Dieu connaissaient, et dont ils faisaient l'application, suivant les circonstances, dans telle ou telle église, et sans s'inquiéter si ce même motif avait ou non été déjà produit tel nombre de fois et dans des contrées diverses (1)? C'est, là, une question que des recherches ultérieures viendront, peut-être, éclaircir; quant à nous, il nous suffit d'en avoir, le premier, indiqué la vraisemblance. Mais, ici, je m'arrête pour réserver la possession de faits que l'on énoncera plus tard. |

— This first point established, it remained to vary or differ the combinations of the path, and, there, for the artists, was the real work. But, although this point has to be determined from the only remaining plans, the result somewhat diminishes their merit. We see the same arrangements reproduced in various places within the same country/region.These variations, may have been made to fool the eye, or to obtain decorative variety, sometimes in dark, sometimes in clear stones. I add also that I found a identical resemblance between compositions from France and from Germany, and this observation proves to us that the artists, sometimes, hardly expended much imaginative effort. On this point, should one admit this was the only indication of thought, or is it more appropriate, frankly, to see the copies as resulting from models, or from patterns that all the guilds of "landlords of God" knew, and of which they made use, depending on the circumstances, in this or that church, and without worrying whether this motif had or not already been used this number of times and in different countries. (1a) It is, then, a question that future research will, perhaps, clarify; as for us, it suffices for us, firstly, to have indicated the likelihood. But here I stop in order to reserve possession of facts that we will set out later. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| Quelques autres questions, presque aussi intéressantes, viennent encore se rattacher à cette étude. Dans le nombre, je signale d'abord celle des particularités decoratives, telles qu'appendices, établis, comme au labyrinthe de Reims, en dehors de la composition ; puis, les dalles ornées du centre, ainsi qu'il y en eut à Amiens, etc. ; sujets divers que nous essaierons d'approfondir dans notre Supplement. | Some other questions, almost as interesting, can be included as well in this study. In that number, I would first point out that of the decorative features, such as additions established outside of the composition as at the labyrinth of Reims, or tiles adorning the centre, as was put in Amiens, etc. ; various topics that we will try to expand in depth in our planned Supplement. | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Enfin, il est une dernière remarque : c'est qu'en lisant le nom des lieux où se trouvent ces labyrinthes, on acquiert la preuve qu'ils étaient presque exclusivement établis dans les cathedrales, dans les grandes églises monastiques, etc., c'est-a-dire dans les constructions qui exigèrent, de la part des architectes, les plus grands efforts de talent, de génie et d'imagination ; les monuments religieux d'un ordre secondaire semblent en avoir été dépourvus. Or, leur présence, dans ces seuls édifices, n'aurait-elle pas une signification quelconque, mais plus spécialement relative à l'art; et dans ce cas, ne pourrait-on en tirer, par exemple, cette conclusion : que ces plans de labyrinthes n'avaient point, à l'origine, un but exclusivement religieux, mais qu'ils étaient plutôt, selon quelque vraisemblance appuyée sur des documents, qu'ils étaient plutôt la figuration d'un prétendu plan d'édifice' l'une des merveilles architecturales de l'ancien monde, à laquelle on fit une réputation qui s'est transmise a travers les siecles, et qui, arrivee à une certaine epoque, devint, dans l'esprit des hommes du moyen âge, comme la caractéristique ou le synonyme de toute grande enterprise, c'est à-dire une espèce de sceau que l'architecte plaçait pour consacrer son œuvre? Il se peut aussi que l'Église, sans détourner l'intention, ait, plus tard, affecté ce plan à une autre destination; mais dans tous les cas, on ignorerait encore si cette pensée lui est venue directement, ou s'il faut l'attribuer a la ferveur de quelque pieux laïc, qui aurait voulu y voir une représentation du Chemin dit de Jerusalem. Espérons que les recherches et les découvertes expliqueront tout cela, un jour!... |

Finally, there is one last remark: it is only by reading the names of the places where these labyrinths are found, that one obtains evidence that they were almost exclusively established in cathedrals, in large monastic churches, etc., that is to say in constructions that required, on the part of architects, the greatest efforts of talent, engineering and imagination; religious monuments of a secondary nature seem to have been deprived of them. [From here to the question mark is one rhetorical question, so put your concentration cap on! A simplication is provided here.] Yet their presence only in this type of buildings, would it not have some significance, even more especially concerning to art, and in this case, could we not draw, for example, this conclusion: that these maze plans originally did not have an exclusively religious purpose, but rather they were, with some probability supported by documents, the representation of an alleged building plan, one of the architectural wonders of the ancient world, which gained such a reputation that it has been passed down through the centuries, and which became, in the minds of men of the Middle Ages, the characteristic of, or synonymous with, any large undertaking, that is to say a kind of seal the architect placed to sign his work? It may also be that the Church, without deflecting that intention, had later assigned this plan to another destination; but in all cases, one does not know whether this thought came to the Church directly, or whether it should be attributed to the fervour of some pious layman, who wanted to see a representation of what is called the Way of Jerusalem. Let's hope the research and discoveries explain it all one day! ... Translation © 2016 abelard.org. All rights reserved. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

end note |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

Illustrations of labyrinths included in cathedral plans of labyrinths by Jules Gailhabaud

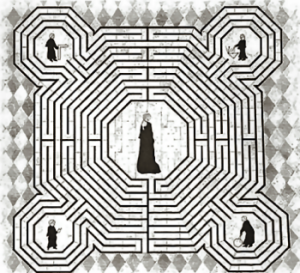

To reach the centre of both the maze at Amiens and that at Saint Quentin, the participant must follow the black line, rather than the white line as in other labyrinths such as those at Reims and Bayeux.. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

Saint-QuentinThe labyrinth at the Basilica of Saint-Quentin is, essentially, the same as the labyrinth at Amiens.

Amiens

A : Bishop

Evrard de Fouilloy +1222

[From Histoire de la ville d'Amiens: depuis les Gaulois jusqu'en 1830 by Hyacinthe Duseve, 1835, vol. 1 pp. 174-6] The original labyrinth at Amiens was constructed in 1288, being 12.8 metres (42 feet) in diameter. It was destroyed in 1825. The drawing below appears to have been made from before that labyrinth's destruction … or maybe not.

labyrinth design similarities and confusionsIf you take the drawing by Gailhabaud (a bit above), and reverse it black to white and white to black (similarly to making a photographic negative), and then flip that reversed image left to right, magically it becomes the pattern for the present Amiens labyrinth. Further, note that the actual Amiens labyrinth has a redundant and confusing black line surrounding it, as you can see just below. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

la basilique Notre-Dame de Saint-Omer

Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Bayeux

«Les Carrelages émaillés du Moyen-Age et de la Renaissance»

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

«Les Carrelages émaillés du Moyen-Age et de la Renaissance», pp. 51-52 |

"Glazed tiles from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance", pp. 51-52 |

La salle capitilulaire de Bayeux est une des plus belles qu‘un puisse voir; elle renferme en outre un magnifique carrelage en terre cuite vernissée du XlVe siècle. Au centre, ou y voit, en guise de rosace, un fort beau labyrinthe de 3 mètres 80 de diamètre. construit dans le même système que le pavé, avec des normaux émaillès; nous en donnons le dessin en regard. Rien que l'émail du pavé ait disparu presqu‘en entier sous le frottement des pieds, il est encore très facile de recoonnaître la décoration première. La voie est composée de carreaux carrés à fonds bruns avec dessins jaunes. D‘autres briques, complètement noires et moins larges que les autres, forment les lignes de séparation, tandis que d‘autres briques, d'un jaune clair, indiquent les points de communication d‘une ligne concentrique à une autre; chacune de ces lignes est elle-même pavée dans tout son parcours en carreaux du même dessin. Les documents relatifs à la cathédrale de Bayeux ne donnent aucun renseignement sur ce labyrinthe et sa destination. Une tradition tendrait néanmoins de faire considérer le parcours de cette figure comme un moyen de punition infligé aux chanoines. Nous pensons que cette tradition, qu‘aucune preuve ne vient corroborer, n‘est point la vraie, et qu'il ne faut voir dans l'usage de ce labyrinthe qu'une pratique de dévotion recommandée aux chanoines, et que le temps aura fait tomber en désuétude. |

The chapter hall of Bayeux is one of the most beautiful that can be seen. It also contains a magnificent floor of glazed terracotta tiles from the 14th century. In the centre, can be seen, like a rosette, a beautiful labyrinth, 3 metres 80 in diameter, built using the same method as the pavement, with natural glazes; see the drawing opposite [just above on this page]. Just the glazing of the pavement has disappeared almost entirely under the friction of feet; it is still very easy to recognise the original decoration. The route is composed of square tiles with a brown background and yellow designs. Other bricks, completely black and narrower than the others, form the dividing lines, while yet other bricks, of a light yellow, indicate the points of communication from one concentric line to another. Each of these lines is itself paved throughout its course in tiles of the same design. The documents relating to the cathedral of Bayeux give no information on this labyrinth and its purpose. A tradition, however, would tend to consider the course of this figure as a means of punishment inflicted on the canons. We think this tradition, of which there's no proof to corroborate it, is definitely not true, and that we must see in the use of this labyrinth only a practice of devotion recommended to the canons, and that in time it [unclear whether "it" is the laybrinth or the custom] had fallen into disuse. Translation © 2018 abelard.org. All rights reserved. |

Formed of incised lines filled in with lead, it was destroyed in 1769, during "The Enlightenment". A similar specimen in Auxerre Cathedral was demolished about 1690.

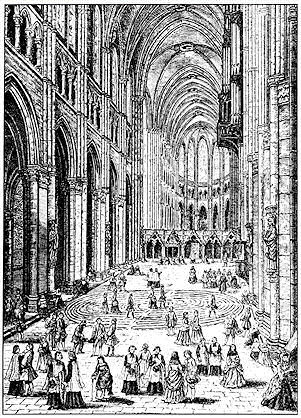

The Labyrinth of Reims was built before the coronation of Philip the Fair [Philippe le Bel], celebrated 6th January 1286, the work being directed by Bernard de Soissons.

In the eighteenth century, children and ‘idlers’amused themselves by following the lines of the labyrinth, crisscrossing in every direction. The clergy, in particular a certain Canon Jacquemart, disturbed by this game, decided to remedy the situation, in 1778 or1779, by removing the labyrinth. An over-generous canon provided a thousand pounds and the destruction completed without it being thought to save the slightest piece of this precious monument.

Fortunately, at the end of the previous century, Jacques Cellier had made a detailed sketch of the labyrinth [placed in a manuscript collection of the National Library, it was also reproduced in several archaeology works] but without details of the legends accompanying the effigies. However, there were two records made of those.

Pierre Cocquault, canon of Reims who died in 1645, recorded the legends, in his manuscript memoirs [a copy was put in the Reims town library]. The other recording of the legends was taken at the time of the destruction, being published in a local daily paper, Affiches rémoises dated 28 June 1779. Although the legends to the labyrinths were deteriorating even in Cocquault’s time, these two records together provide enough information to know who the effigies represent.

In the centre is Archbishop Aubry de Humbert who laid the first stone of the cathedral in 1211. The four smaller figures are the first four masters of works [maître d’oeuvre]. Entering from the main west door:

It is thought that the labyrinth was built as the collective signature of the cathedral's master builders, designed with reference to that of the Cathedral of Amiens.

The labyrinth was certainly completed before the start of the 14th century, as it does not include another of the early maître d’oeuvre, Robert de Coccyx, who died in 1311.

right: labyrinth at Chartres, c. 1750 |

|

The floor labyrinth was laid in 1205, and was used by the monks for walking contemplation. It is still used by pilgrims. There is only one path 964 feet long. At the centre of the labyrinth there used to be a metal plate showing figures of Theseus, Ariadne, and the Minotaur, the characters in the classical myth of the Minos labyrinth.

The circumference of the labyrinth is 40 metres (131 feet).

Bayeux: 3.78 m diameter

Sens: 9.14 m diameter

Reims: 10.36 m width

Saint-Quentin: 10.5 m width

Saint-Omer: estimated 10.85 m

Amiens: 11,6 m diameter, 234 m long

Chartres : 12,89 m diameter, 261,55m long

In times past, what is generally called a labyrinth was given other names. Here are some:

'Dedale', referring to the architect of the maze of Knossos, Dædalus.

'Meandre' (meander).

'Chemin de Jerusalem' or "the road to Jerusalem", a name derived from the understanding that cathedral labyrinths were sometimes used as a kind of short pilgrimage by those unable or unwilling to do a full pilgrimage. Apparently, indulgences could be earned that were equivalent to a pilgrimage to Jerusalem or Saint Jacques de Compostela.

Relating

to this, the labyrinth's centre was called 'ciel' (heaven) or "Jérusalem".

'La Lieue' , or the League. This was not because a labyrinth, such as that at Chartres, was a distance of a league or about 4 kilometres, but because it was a long way. It is also said that the time to travel a major labyrinth while kneeling took as much time as walking a league!

Possibly, la lieue had some etymological connection with an old Gaulish measurement leuca, leuga or leuva, that was 1500 paces long.

'Via Dolorosa', painful way, evoking the path that Jesus took from the court of Pontius Pilate to reach Golgotha.

The Labyrinthine Path of Pilgrimage by Tessa Morrison.

This is not a bad essay that you might like to read [7-page .pdf]

L'architecture du 5me au 17me siècle et les arts qui en dépendent, Volume 2 by Jules Gailhabaud, 1858

Histoire de la ville d'Amiens: depuis les Gaulois jusqu'en 1830 by Hyacinthe Duseve, 1835

Récreations Mathematiques by Edouard Lucas, 1822

Dictionnaire françois de la langue oratoire et poétique by Joseph Planche, Librarie de Gide, Paris, 1822

Mazes and Labyrinths: A General Account of Their History and Development |

||

|

LONGMANS, GREEN AND CO. |

Project Guttenberg scanned copy |

| Les Carrelages émaillés du Moyen-Age et de la Renaissance by Emile Amé |

||

|

A. Morel et Cie, Editeurs, Paris 1859 |

|

email abelard@abelard.org © abelard, 2016, 21 january the address for this document is https://www.abelard.org/france/cathedral-labyrinths-mazes.php |