|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

Citizenship Curriculum— abelard25-year update |

|

| r |

|

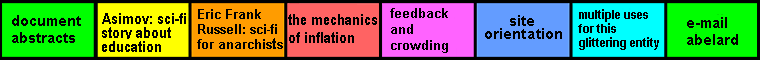

| Citizenship curriculum is one in a series of documents examining how to improve public behaviour in society. | ||||||

| introduction to franchise discussion documents | citizenship curriculum | The logic of ethics | ||||

| franchise by examination, education and intelligence | power, ownership and freedom | |||||

| • Kantsaywhere by Francis Galton • from In the Wet by Neville Shute • historic UK vote allocation |

||||||

| how to teach a child to read using phonics | how to teach a person number, arithmetic, mathematics | |||||

| for

related short briefing documents examining the world’s

growing crisis, start at replacing fossil fuels, the scale of the problem |

||||||

| While, for convenience and clarity, this document is broken into categories by various means, it is essential to keep in mind the seamless and interactive nature of all education and knowledge. All ‘subjects’ interact and it is important that all educators make this clear to any persons that they intend to enlighten and enable. | ||||

CONTENTS |

|

|||

Brain washing—otherwise known as bias

|

||||

Objectives

Areas of studyPsychology: [5]

|

advertising disclaimer |

|||||||

Detailed curriculum (currently under development)Key to link buttons in the curriculum sections.

Concepts |

| 1 | Theory and action. | ||

| 2 | Being calm. | Regular moments of calm. Practice in the context of excitability. | |

| 3 | Blame and excuses. | There is no blame, there is no excuse. | |

| 4 | ‘Equality’ and diversity. | ||

| 5 | Fairness, justice, the rule of law, rules, law and human rights. | ||

| 6 | Freedom and order. | ||

| 7 | Ownership and independence | ||

| 8 | Individual and community. Collectivism, statism, liberalism. | ||

| 9 | Power and authority. Problems are linked to over control and will to power. | understanding the current political world | |

| 10 | Rights and responsibilities. | Your right to receive

goods on purchase, your duty to supply. Do you have the right to walk through a wall. A right implies an ability to enforce that right. |

|

| 11 | Democracy and autocracy. |

||

| 12 | Co-operation and conflict. | See humans killing humans | |

| 13 | Controlling anger. Instinct. Force. | See understanding a species under stress | |

| 14 | Foresight. | ||

| 15 | Negotiating. Telling people what you want. | ||

| 16 | Parenting. | Useful book for discussing parenting with children. |

|

| 17 | Analysing. | What is a just war. | |

| 18 | ‘Work’ and money. Why are you paid? | Why are you paid? Is it more costly to interact with pleasant people or with nasty ones? |

|

| 19 | Reason is possible in relationships, just as it is in the natural sciences. | ||

| 20 | Externalised costs, evolution and co-operation, consciousness. | ||

| 21 | What is the common good? Forms of government. | See authoritarianism and liberty | |

| 22 | The way things are. The way we want things to be. How we get from one to the other. | If I wanted to go to Land’s End, I wouldn’t be starting from here. | |

| 23 | ‘Thinking’ and

‘fact’. |

Values and dispositions: what is ‘good’? |

| 24 | Looking ahead. |

Statistics. Bayes theory (probability and observation). Processing and analysing information. |

|

| 25 | One universal ‘rule’ is balance. | ||

| 26 | Human rights. |

||

| 27 | What is law? Why obey laws? Legitimacy of laws. | Witness reliability. | |

| 28 | Concern for the environment. Why bother? |

||

| 29 | Calm – humility – tolerance. | ||

| 30 | Kindness. (See Jeremy Bentham). | Utilitarianism. | |

| 31 | Time to think. Patience. Trusting. | ||

| 32 | Concern to resolve. A disposition to work with, and for, others with sympathetic understanding, kindness. | ||

| 33 | Proclivity to act responsibly: that is care for others and oneself; pre-meditation and calculations about the effect actions are likely to have on others. | Acceptance of responsibility for unintended or unfortunate consequences (COBA – Cost-benefit Analysis). What does reflection mean? What is a responsible act? |

|

| 34 | Practice of tolerance. Why be tolerant? | It is common that minorities preach tolerance, on becoming a majority groups tend not to practise tolerance. |

|

| 35 | Judging and acting by a moral code. What is a moral/ethical code? |

Religions as social codes. Rigidity/precedents. Rules as a substitute for thought. | |

| 36 | Why and how does such a code arise (see Good Natured). | See Power, ownership and freedom | |

| 37 | Courage to defend a point of view.

What is courage? |

Being

courageous does not mean lacking fear. “As an old soldier I admit the cowardice: it’s as universal as sea sickness, and matters just as little.” [2a] |

|

| 38 | Is it OK to be frightened? Going with the crowd. | ||

| 39 | Dangers of crowd psychology. |

Konrad Lorenz. War (?), peer pressure, excitement and panic of crowds. See herds and the individual - sociology, the ephemeral nature of groups |

|

| 40 | Individual initiative and effort. Responsibility. | Self-defence. | |

| 41 | Run, fight, withdraw (that is, see the enemy and run). | See Gangs, war, and excitement, under development. | |

| 42 | Willingness to be open to changing one's opinions and attitudes, in the light of discussion and evidence. | ||

| Determination to act justly. What does ‘just’ mean? | See 'just war' |

||

| 44 | Commitment to ‘equal’ opportunities. | ||

| 45 | What does ‘equality’ mean? Does it mean anything? | ||

| 46 | Active citizenship. ‘Improving’ the world. | See 'And Then There Were None' by Eric Frank Russell | |

| 47 | Voluntary service. | Monetarisation. |

|

| 48 | Meaning of human dignity. Acting well out of self-respect. |

"What you avoid suffering yourself, seek not to impose on others." Seneca, On Anger, 3.12 |

|

| 49 | Sentience. | Study to be carried out in context of power, ownership and freedom |

| advertisement |

Developing skills – how to achieve change? |

|

General

knowledge, discussion and |

| 74 | Contemporary issues and events at local, national, EU, Commonwealth and international levels; corporations. | ||

| 75 | Democratic communities, including how they function and change. | For contrast, see for Socialism and peace: the Labour Party's programme of action, 1934 | |

| 76 | The interdependence of individuals. | ||

| 77 | Local voluntary communities and organisations. | ||

| 78 | Diversity, dissent and social conflict. | the illusion of groups | |

| 79 | Why do people argue? Language, resources. | referring to reality | |

| 80 | Legal and moral rights and responsibilities of individuals and communities. | intrusive ‘help’ | |

| 81 | Britain’s parliamentary and legal systems at local, national, European, Commonwealth and international level, including how they function and change. | ||

| 82 | International law and international bodies, Amnesty International. | ||

| 83 | Human rights charters and issues. European Bill of Rights. United Nations rights charters. United States constitution. (Links to copies of these documents are available on-line at Declarations.) | ||

| 84 | The rights and responsibilities of citizens as consumers, employees and community members. | ||

| 85 | The economic system as it relates to individuals and communities. | See Citizen’s wage, with commentary on the misconstruing of property, ownership and subsidy | |

| 86 | International comparisons. The nature of corporations and businesses. | ||

| 87 | War and police. The social use of force. Is force effective? | Legitimacy | |

| 88 | Sustainable development and environmental issues.[3] |

|

|

| 89 | Living in groups. Nation, community, ‘family’, monastic, recluse. | ||

| 90 | Freedom of information. Bill of rights. How they relate to education and to law. | ||

| 91 | Keeping reasonably fit and safe. Not becoming a burden upon yourself

and others, because of carelessness and irresponsibility. |

Brain washing—otherwise known as biasThe following is verbatim from Education for citizenship and the teaching of democracy in schools[1]: “Summary of the Statutory Requirements

This is followed by the next note:

|

advertising disclaimer |

Later, Education for citizenship etc [1] goes on to suggest three approaches to teaching: “(a) The ‘Neutral Chairman’ This requires the teacher not to express any personal views or allegiances whatsoever, but to act only as the facilitator of a discussion, ensuring that a wide variety of evidence is considered and that opinions of all kinds are expressed.” I thoroughly disapprove of such a stance. I regard it as an abnegation of responsibility. A teacher’s job is to widen the world of the young, not seek merely to keep out of trouble. Teachers have a duty to bring knowledge to the young, not to just stand idly by, while the young discuss their own limited world and prejudices. “(b) The ‘Balanced’ approach by which, as teachers ensure that all aspects of an issue are covered, they are expected to express their own opinions on a number of alternative views to encourage pupils to form their own judgements. This requires teachers to ensure that views with which they themselves may disagree, or with which the class as a whole may disagree, are also presented as persuasively as possible – in other words, to act on occasion if necessary, as ‘Devil’s Advocate’.” While I regard this as a considerable improvement, I object to the pretence and dishonesty involved in the ‘devil’s advocate’ stance. I also object to ‘persuasively as possible’. A teacher owes absolute honesty to others: the ‘devil’s advocate’ stance confuses that necessity. Further, a teacher’s duty is to teach people how to recognise and allow for advocacy, not to implicitly teach a promotion of rhetoric and other dishonesty. Unfortunately in this primitive culture, teachers are not able to be entirely truthful towards others, for they are quickly likely to find vested interests exploiting honesty as a weakness. For adequate professional standards in teaching it will be needful to introduce a Hippocratic-type oath and special privileges of the type presently accorded to law courts and parliament. When education was in the hands of the Church, teachers were subject to clerical law, separate from the state. Such a system should be reconsidered. “(c) The ‘Stated Commitment’ approach in which teachers openly express their own views from the outset, as a means of encouraging discussion, during which pupils are encouraged to express their own agreement or disagreement with the teacher’s views.” This approach is a necessity to good teaching, for all people including teachers have their own interests and views. The educational system should offset problems of bias by opening education to a wide variety of advocates with varying views, all the while encouraging ‘pupils’ to discuss and analyse different options and approaches to life. Trust the young to learn. Do not wrap them in cotton wool. Education for citizenship etc [1] then continues in the following manner in an attempt to avoid as much responsibility as possible, by sitting firmly on the fence. Such is our ‘culture’.

|

|

Teacher training

|

The nature of the institutionIntegrating the school with the community instead of accepting school as a dumping ground for children. Refusal to accept a forbidding and insular response from schools. Intrinsic nature of being in a social situation, for instance like a school. Compartmentalisation. Education Otherwise

|

There is a squishy but useful review article on fact-based strategies for the prevention of failure from early childhood (55-page .pdf, with references). |

End notes |

|||

| 1 | Education for citizenship and the teaching of

democracy in schools [88-page .pdf, with added slush in the form of appendices] This is a very useful summary introduction from which I have cribbed at will and then hacked, improved and expanded while building this document. Any person interested in education should download a copy of this document. The terms of reference for this publication follow: [Note very carefully the highlighted sections.]

From the preface I quote the following: 1.1 We unanimously advise the Secretary of State that citizenship and the teaching of democracy, construed in a broad sense that we will define, is so important both for schools and the life of the nation that there must be a statutory requirement on schools to ensure that it is part of the entitlement of all pupils. It can no longer sensibly be left as uncoordinated local initiatives which vary greatly in number content and method. This is an inadequate basis for animating the idea of a common citizenship with democratic values. |

||

| 2 | Democracy and Elections, R.S. Katz, 1997, OUP, (approx. £40, 0195044290) | ||

| 2a | George Bernard Shaw (1856 – 1950), Man and Superman, 1903, act 3 | ||

| 3 | Factor Four: Doubling Wealth, Halving Resource Use,

von Weizsacker, Lovins and Lovins, 1998, Earthscan Publications Ltd., 1853834068, £12.95 (amazon.co.uk) |

||

$11.20 (amazon.com) £10.13 (amazon.co.uk) |

|

||

For subsidiary discussion on the replacement of fossil fuels; where there are also further links. There is a growing bank of resources regarding the environment in the abelard.org news zone, see in particular ecology, oil, science, (associated archives index). |

|||

| 4 | Children in Chancery, Joy Baker, Hutchinson & Co. Ltd., 1964 | ||

| 5 | For expanded related information, refer to Reading

References on this web-site under the heading, Relational Training. |

||

| 6 | Note the implicit suggestion that points of view should not be given ‘equal attention’. | ||

| 7 | Note the overt fear of accusation. |

||

© abelard, 1999, draft release 4.1 the address for this document is https://www.abelard.org/civil/civil.htm 3180 words |