|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

a phonetics chart for british englishby the auroran sunseta briefing document |

||

|

|

|||

| A phonetics chart for British English is a supplementary document to how to teach a child to read using phonics [synthetic phonics]. |

| on teaching reading | how to teach a person number, arithmetic, mathematics | ||

The following tables contain the phonetic symbols [1] for the standard sounds used in English. There is one table for most vowels and one table for most consonants, as well as a third table for additional sounds. Along with each symbol, there are two example words, with the relevant sound highlighted. The first example is always a very simple word that most learners will already know. The second example is usually slightly more challenging. After each symbol, there is a link to an illustrative mp3. Each mp3 has the sound repeated three times on its own, followed by the two examples. Most browsers will play the mp3 automatically when you click the link. If you have problems, right click on the link and download the mp3. You can then listen to the example in a music player such as iTunes or WinAMP. All examples assume standard British English pronunciation - sometimes known as “Queen’s English”, “King’s English”, “Received Pronunciation” and “BBC English”. Strangely, now that regional accents have become fashionable, BBC English is one of the few accents you are unlikely to hear from a modern BBC presenter. Americans, and other ‘colonials’, may find some examples confusing - if unsure, please listen to the mp3 for that sound. Each file is approximately 30kB - about the same as a small image. Note that because consonant sounds are by definition whispered, it is extremely difficult to say those sounds clearly and loudly on their own. Thus, I have added an ‘-er’ or schwa sound [mp3 link] on the end of each consonant sound: I say [də] [2], not [d]. Obviously when saying a word yourself, you do not add that schwa sound after every consonant! [3] The sound, or phoneme, associated with each phonetic symbol [like those in the table below] does not change from accent to accent, or language to language, instead different symbols are used to write the different pronunciations. For example, the word “fast” has a long vowel sound in Queen’s English, but a short vowel sound in American English (and Northern British English!). Thus for King’s English, the pronunciation of “fast” is written as [faːst]; and for American English, the pronunciation of “fast” is written as [fæst]. Therefore, while your pronunciation of the example words may well differ from ours - as demonstrated on the mp3s - your pronunciation of the phonetic symbols themselves should not differ significantly from ours! Once you can recognise the phonetic symbols, you should be able to look up and read the pronunciation of any word in any dictionary [you need to learn some extra sounds/symbols, not shown here, for many foreign languages]. [4] |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ʌ up muck click for mp3 |

aː hard calm click for mp3 |

æ cat flagellate click for mp3 |

ə away dictator click for mp3 |

ɛ head emperor click for mp3 |

| ɜː learn herbal click for mp3 |

ɪ six imp click for mp3 |

iː see evil click for mp3 |

ɒ hot oxymoron click for mp3 |

ɔː call awesome click for mp3 |

| ʊ wood whoops! click for mp3 |

uː you moody click for mp3 |

aɪ I irate click for mp3 |

aʊ ow! spout click for mp3 |

oʊ əʊ go Mona Lisa click for mp3 |

| eə air wary click for mp3 |

eɪ say alien click for mp3 |

ɪə ear happier click for mp3 |

ɔɪ oil spoilt brat click for mp3 |

ʊə tour demur click for mp3 |

| b baby bonanza click for mp3 |

d did dilettante click for mp3 |

f fish fife click for mp3 |

g gift glimmer click for mp3 |

h hello hell-raiser click for mp3 |

| j yes younger click for mp3 |

k back capitulate click for mp3 |

l leg legerdemain click for mp3 |

m lemon manipulate click for mp3 |

n no notorious click for mp3 |

| ŋ sing humdinger click for mp3 |

p pet peculiar click for mp3 |

r red resistance click for mp3 |

s sun sucker click for mp3 |

∫ she splash click for mp3 |

| t tea telemetry click for mp3 |

t∫ chess childish click for mp3 |

θ think theory click for mp3 |

ð mother themselves click for mp3 |

v voice vex click for mp3 |

| w we sweltering click for mp3 |

z zoo sneeze click for mp3 |

ʒ pleasure measured click for mp3 |

dʒ gym jamboree click for mp3 |

additional

sounds,

including those imported from other languages [5]

| ɑ bâtiment [Fr.: building] pâte [Fr.: pastry] click for mp3 |

ɑː barn father click for mp3 |

a mari [Fr.: husband] patte [Fr.: foot, paw] click for mp3 |

(ə) beaten button click for mp3 [7] |

e pet bébé [Fr.: baby] click for mp3 |

| ɜː yurt bird click for mp3 |

eː |

ɛː Führe [Ger.: load] click for mp3 |

ɔ boeuf [Fr.: beef] leur [Fr.: their] click for mp3 |

oː Sohn [Ger.: son] click for mp3 |

| øː Goethe [Ger.: a name] click for mp3 |

u douce [Fr: soft.] fou [Fr.: mad] click for mp3 |

ʏ |

y du [Fr.: of the] pur [Fr.: pure] click for mp3 |

yː grün [Ger.: green] click for mp3 |

| ɛ~ fin [Fr.: end] lin [Fr.: flax, linen] click for mp3 |

ɑ~ franc [Fr.: franc] clan [Fr.: clan] click for mp3 |

ɔ~ bon [Fr.: good] long [Fr.: long] click for mp3 |

œ~ un [Fr.: one] brun [Fr.: brown] click for mp3 |

ɛə |

| ɔə boar saw click for mp3 |

aɪə fiery beer click for mp3 |

aʊə sour bower click for mp3 |

||

| (r) her fur click for mp3 |

hw when whine click for mp3 |

ŋɡ finger banger click for mp3 |

ʎ seraglio [It.: menagerie] click for mp3 |

ɲ cognac [Fr.: brandy] gnôle [Fr.: hooch] click for mp3 |

x |

ç ich [Ger.: I] click for mp3 |

ɣ |

c baardmannetjie [Afrikans: scaley-feathered finch (Sporopipes squamifrons)] click for mp3 [8] |

ɥ huit [Fr.: eight] cuisine [Fr.: kitchen] click for mp3 |

[Note that phonetic symbols such as a or ʊ may be modernised to display as ɑ or u.]

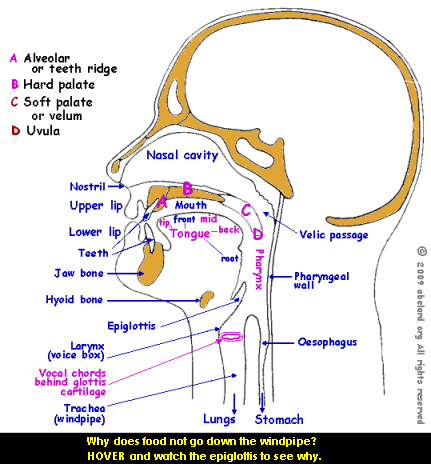

How a consonant is articulated, or spoken, involves controlling and manipulating your breath leaving the mouth, using the lips, teeth, tongue and the interior of the mouth, as well as the speed and strength of the air flow.

Consonants are of two types, pulmonic and non-pulmonic, though most languages only include the pulmonic type. Pulmonic consonants are produced using pressurised air expelled (outward-going) from the lungs, while non-pulmonic consonants comprise ejective, implosive and click sounds. Ejective and implosive sounds use glottalic airflow, while clicks use velaric airflow.

Cross-section of the

human head, labelling components of the vocal tract

Consonants formed without pulmonic airflow. This type of consonants instead are formed with velaric airflow (clicks) or glottalic airflow (implosives and ejectives).

Velarisation [this section is a beta release]

Velarisation is used to pronounce or supplement the pronunciation of a consonant with an articulation at the soft palate, the back of the tongue being raised towards the soft palate during the articulation of the consonant.

Examples of velarised consonants in English are the ‘l’ in milk and in build, described as a dark l. Further understanding may be helped by pronouncing alternately the consonants ‘k’ and ‘t’, where ‘k’ is velar and ‘t’ is dental . Other velar sounds are ‘g’, ‘Å‹’ and ‘x’.

More technically,

To be developed:

Bilabialisation

Labiodentalisation

Dentalisation

Alveolarisation

Postalveolarisation

Retroflexive

Palatalisation

Uvularisation

Labialisation

Pharyngealization

Glottalisation

how

to add phonetic symbols to a webpage,

includes symbol descriptions

Unlike with Microsoft Word, copying and pasting these symbols into the HTML source code for your website will probably not work. To add phonetic symbols to an HTML document, you must type special “HTML entities”. An HTML entity is something that starts with an ampersand (&) and end with a semicolon (;), which browsers translate to a special character rather than displaying directly. The following table contains the HTML codes (entities) for all the symbols used above that aren’t just standard alphabetic characters. For those with older setups having trouble seeing these characters, please see here.

| symbol | name & description | what to type |

|---|---|---|

| ː | extended sound mark | ː |

| ˜ | tilde (sometimes called

a swung dash): in this context, this symbol indicates a nasal vowel. The tilde is frequently indicated over or across the letter concerned. |

˜ |

| ʌ | carot: an upside-down ‘v’ | ʌ |

| ɒ | script ‘a’ turned 180 degrees | ɒ |

| æ | aelig—a-e ligature:

a lowercase ‘a’ linked to a lowercase ‘e’ |

æ |

| ə | schwa : an ‘e’ rotated 180 degrees | ə |

| ɜ | a back-to-front lowercase Greek epsilon | ɜ |

| ɛ | lowercase Greek epsilon | ɛ |

| ɪ | a small capital ‘i’ | ɪ |

| ɔ | an ‘o’ open

on the left-hand side, or a back-to-front ‘c’ |

ɔ |

| ʊ | an upside-down Greek capital omega | ʊ |

| ŋ | engma: an ‘n’ with a ‘j’ hook at bottom right | ŋ |

| ∫ | esh: like the integral symbol used in mathematics | ∫ |

| θ | theta: a lowercase Greek theta | θ |

| ð | eth: a lowercase Greek delta with a bar through its tail | ð |

| ʒ | ezh: like a stylised ‘3’ | ʒ |

| ɑ | open a: script ‘a’ | ɑ |

| ø | e -slash (front-rounded

vowel): ‘o’ crossed by a diagonal line |

ø |

| ʏ | near-close near-front

rounded vowel : small capital letter ‘Y’ |

ʏ |

| œ | o-e ligature: a lowercase ‘o’ linked to a lowercase ‘e’ |

œ |

| ʎ | palatal l: similar to a mirror-image lambda | ʎ |

| ɲ | IPA palatal n: an ‘n’ with a ‘j’ hook at bottom left |

ɲ |

| ç | c cédilla: ‘c’ with a comma under the letter | ç |

| ɣ | IPA gamma: similar to a lowercase Greek gamma with a looped foot |

ɣ |

| ɥ | front-round glide:

an inverted, reversed lower-case ‘h’ |

ɥ |

There doesn’t seem to be much of a serious difference between the terms ‘phonetics’ and ‘phonics’. However, for what it is worth:

Phonics is a term from the 17th century. It is used to talk about the relationship between sound and spelling, especially when teaching English reading and spelling.

Phonetics is a term from the mid-19th century.

It is used to talk about the study of speech sounds.

Some users with older operating systems and browsers may have problems seeing the phonetic symbols properly. You may for example see a box or a question mark instead of the symbol. This problem should not occur on any post-2000 operating system, such as Mac OSX, Windows 2000, Windows XP, Windows Vista, etc.

For those having this problem, here is one solution. Download and install the Mozilla Firefox browser. Firefox is free and is also by far the best browser available on the market today. We would recommend using Firefox even if you did not have this problem to solve.

You will also need to install a font that contains

the IPA (International Phonetics Alphabet) characters.

Here for example is Lucida

Sans Unicode in TTF (True-Type Font) format. Download

that file and copy it to your Fonts Folder - usually

C:\Windows\Fonts under older versions of Windows.

Next open your Firefox Preferences. In the Fonts area,

select "Lucida Sans Unicode" from the dropdown. You

should now be able to see phonetic characters, and

many others, without difficulty.

Note that is very important

when teaching reading that you do not add the

‘-er’ or schwa sound onto the end of consonants,

because it will tend to confuse and cause the words

to be synthesised incorrectly. For example, if you

teach your child to pronounce ‘c’ as [cə] and ‘t’ as [tə],

then when they try to pronounce ‘cat’,

it will become [cəætə] (ker-a-ter! ...kerater), rather than [cæt] (k-a-t...kat)!

The pronunciation guides in

dictionaries also have accent marks over the emphasised

vowel sounds. The accent mark looks like an French

acute accent, like in é.

|

© the auroran sunset and abelard.org, 2007, 12 february

the address for this document is https://www.abelard.org/briefings/phonetic_chart_british_english.php 2000 words |

| latest | abstracts | briefings | information | headlines | resources | interesting | about abelard |